Chapter 48 Raynaud’s Phenomenon

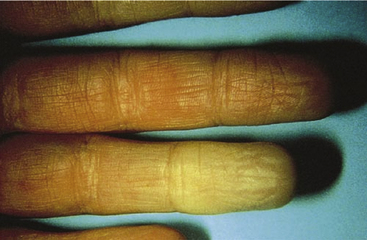

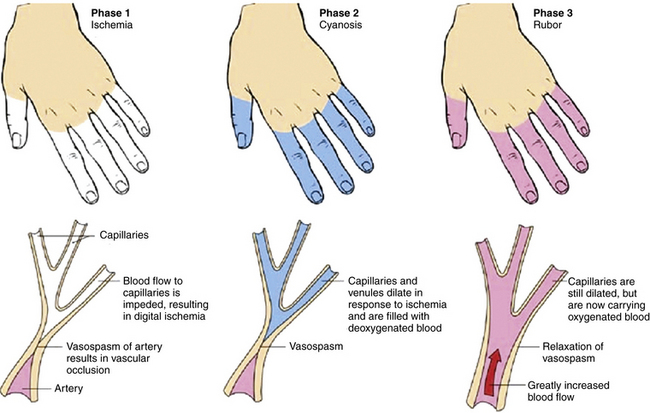

Episodic vasospastic ischemia of the digits was first described by Maurice Raynaud in the quotation above1 (Fig. 48-1). Raynaud’s phenomenon comprises sequential development of digital blanching, cyanosis, and rubor following cold exposure and subsequent rewarming2 (Fig. 48-2). Emotional stress also precipitates Raynaud’s phenomenon. The color changes are usually well demarcated and primarily confined to fingers or toes. Blanching, or pallor, occurs during the ischemic phase of the phenomenon and is secondary to digital vasospasm. During ischemia, arterioles, capillaries, and venules dilate. Cyanosis results from the deoxygenated blood in these vessels. Cold, numbness, or paresthesias of the digits often accompany the phases of pallor and cyanosis. With rewarming, digital vasospasm resolves, and blood flow dramatically increases into the dilated arterioles and capillaries. This “reactive hyperemia” imparts a bright red color to the digits. In addition to rubor and warmth, patients often experience a throbbing sensation during the hyperemic phase. Thereafter, the color of the digits gradually returns to normal. Although the triphasic color response is typical of Raynaud’s phenomenon, some patients may develop only pallor and cyanosis. Others may experience only cyanosis.

Figure 48-1 A patient with Raynaud’s phenomenon.

(From Raynaud M: Local asphyxia and symmetrical gangrene of the extremities, London, 1862, New Sydenham Society. Courtesy Boston Medical Library in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine.)

Figure 48-2 Raynaud’s phenomenon may have three color phases: blanching, cyanosis, and rubor.

(From Creager MA: Raynaud’s phenomenon. Med Illus 2:84, 1983.)

The classification of Raynaud’s phenomenon is broadly separated into two categories: (1) the idiopathic variety, termed primary Raynaud’s phenomenon, and (2) the secondary variety, associated with other disease states or known causes of vasospasm (Box 48-1). Secondary causes of Raynaud’s phenomenon include collagen vascular diseases, arterial occlusive disease, thoracic outlet syndrome, several neurological disorders, blood dyscrasias, trauma, and several drugs.

![]() Box 48-1 Secondary Causes of Raynaud’s Phenomenon

Box 48-1 Secondary Causes of Raynaud’s Phenomenon

Overview of Primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon

Primary Raynaud’s phenomenon, or idiopathic episodic digital vasospasm, is the most common diagnosis of patients who present with Raynaud’s phenomenon.2 The diagnosis is based on criteria originally established by Allen and Brown,3 including (1) intermittent attacks of ischemic discoloration of the extremities, (2) absence of organic arterial occlusions, (3) bilateral distribution, (4) trophic changes—when present, limited to the skin and never consisting of gross gangrene, (5) absence of any symptoms or signs of systemic disease that might account for the occurrence of Raynaud’s phenomenon, and (6) symptom duration for 2 years or longer. If a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), normal nailfold capillary examination, and negative test for antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) are added to these criteria, the diagnosis is more secure.

Women are affected approximately five times more frequently than men. In one large study, the average age of onset of Raynaud’s phenomenon was 31 years; 78% of the patients were younger than 40 when symptoms began.4 Onset of symptoms in women may occur between menarche and menopause. Raynaud’s phenomenon is also known to occur in young children.5,6 Prevalence of primary Raynaud’s phenomenon varies with climate, with 4.6% of the population affected in warm climates, compared with 17% in cooler climates.6 There is a significant familial aggregation of primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Approximately 26% of patients may know of one or more relatives who have the phenomenon, suggesting a genetic predisposition.7

In the vast majority of patients, the fingers are the initial sites of involvement.2 At first, blanching or cyanosis may involve only one or two fingers (Fig. 48-3). Later, color changes may develop in additional fingers, and symptoms occur bilaterally. In about 40% of patients, Raynaud’s phenomenon involves the toes as well as the fingers. Isolated Raynaud’s phenomenon of the toes occurs in only 1% to 2% of patients. Rarely, the ear lobes, tip of the nose, or tongue are affected.

Several studies have correlated Raynaud’s phenomenon with migraine headaches and variant angina, suggesting a common mechanism for vasospasm.8–10 An association with vasospasm in the kidney,11 retina,12 and pulmonary13 vessels has also been described. Further evidence is the report of a family with three generations of systemic arterial vasospastic disease involving Raynaud’s phenomenon, variant angina, and migraine headaches.14 Differences in the responses of pharmacological intervention make the hypothesis of a common mechanism less appealing.15 Propranolol has been successfully used to prevent migraine headaches.16 In contrast, β-adrenoceptor blockers are not beneficial in variant angina and may cause Raynaud’s phenomenon.17,18 Similarly, nitrates are used for variant angina but are not beneficial in Raynaud’s phenomenon and often cause headaches. Ergot alkaloids are effective for treating migraine headaches but can cause coronary and digital vasospasm.19,20

Of all the forms of Raynaud’s phenomenon, primary Raynaud’s phenomenon has the most benign prognosis. In the group of patients identified by Gifford and Hines4 followed for a period of 1 to 32 years (average 12 years), 16% reported worsening of their symptoms, and 38%, 36%, and 10%, respectively, reported no change, improvement, or disappearance of symptoms. Sclerodactyly or trophic changes of the digits occurred in approximately 3% of patients during follow-up, and less than 1% of patients lost part of a digit. In some patients, scleroderma may develop after Raynaud’s phenomenon has been present as the only symptom for more than 20 years. Wollersheim et al.21 reported that measuring ANAs by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon had a positive predictive value of 65% and 71%, and a negative predictive value of 93% and 83%, respectively, for development of a connective tissue disease.

Pathophysiology

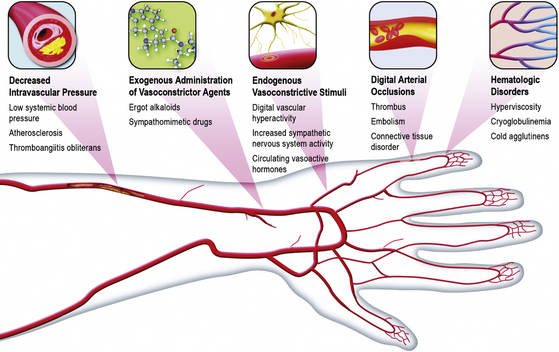

The precise cause of Raynaud’s phenomenon has not been clearly identified. It is quite likely that a variety of physiological and pathological conditions may contribute to or cause digital vasospasm2 (Box 48-2 and Fig. 48-4).

![]() Box 48-2 Possible Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Raynaud’s Phenomenon

Box 48-2 Possible Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Raynaud’s Phenomenon

Vasoconstrictive Stimuli

Local Vascular Hyperreactivity

The observation that episodic digital vasospasm occurs during cold exposure has led several investigators to consider the possibility that Raynaud’s phenomenon occurs as a result of a local vascular hyperreactivity. In 1929, Sir Thomas Lewis observed that following exposure of the finger to cold, vasospasm could be produced even after nerve blockade or sympathectomy.22 These experiments were repeated and confirmed 60 years later.23 Therefore, the vasospastic response of the Raynaud’s phenomenon may occur in the absence of efferent digital nerves. The possibility of local vascular hyperreactivity was examined by Jamieson et al.24 They compared the magnitude of reflex vasoconstriction in each hand following application of ice to the neck while one hand was kept at 26 °C and the other at 36 °C.9 At 36 °C, the reflex vasoconstrictor response was comparable in normal subjects and patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. In the hand cooled to 26 °C, however, reflex vasoconstriction was exaggerated in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. This response led these investigators to hypothesize that digital α1 adrenoceptors were sensitized by cold exposure.

A series of studies by Vanhoutte et al.25 have supported the hypothesis that cooling potentiates the vascular response to sympathetic nerve activation. Vasoconstriction, in response to exogenous norepinephrine, also is increased by cooling. Augmentation of adrenergic-mediated vasoconstriction by cooling occurs despite generalized depression of contractile machinery and diminished release of norepinephrine from sympathetic nerve endings in the vessel wall. The most likely hypothesis is that cold causes changes at the level of the adrenoceptor, such as an increase in the affinity for norepinephrine or greater efficacy of the agonist/receptor complex. Vanhoutte et al.25 have reported that α2 adrenoceptors are more sensitive than α1 adrenoceptors to temperature change. Whereas cooling slightly depresses α1 adrenergic–mediated vasoconstriction, it markedly augments α2 adrenergic–mediated responses. Conversely, warming augments α1-adrenergic vasoconstriction and depresses α2-adrenergic vasoconstriction.26

These experimental observations may have important implications regarding the pathophysiology of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Flavahan et al.27 examined the distribution of α1 and α2 adrenoceptors in arterial tissue from amputated limbs of patients who did not have vascular disease. They reported that α2 adrenoceptors were more prominent in digital arteries. Chotani et al.28 found that human dermal arterioles selectively expressed α2C adrenoceptors. Jeyaraj et al.29 observed that cooling redistributed α2C adrenoceptors from the Golgi to the plasma membrane in human embryonic kidney cells. It is therefore an intriguing observation by Keenan and Porter that the density of α2 adrenoreceptors is increased in platelets from patients with Raynaud’s disease.30

In support of these findings, Coffman and Cohen reported that α2 adrenoceptors were more important than α1 adrenoceptors in mediating sympathetic nerve–induced vasoconstriction in the fingers.31 They administered the α1-antagonist prazosin and the α2-antagonist yohimbine to patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon during reflex sympathetic vasoconstriction caused by body cooling. Whereas prazosin caused no significant change in finger blood flow or finger vascular resistance, yohimbine significantly increased finger blood flow and decreased finger vascular resistance. This study confirmed that postjunctional α2 adrenoceptors are present in human digits and strongly suggested that these receptors contribute to digital vasoconstriction during environmental cooling in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Thereafter, Coffman and Cohen demonstrated that compared to normal subjects, patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon were hypersensitive to the vasoconstrictor effects of clonidine, an α2-adrenoceptor agonist, but not to phenylephrine, an α1-adrenoceptor agonist.31 Cooke et al.32 found that both α1– and α2-adrenoceptor antagonists induced digital vasodilation in patients with acute Raynaud’s phenomenon, yet did not inhibit digital vasoconstriction caused by local digital cooling. Although still speculative, these studies suggest that episodic digital vasospasm may be secondary to a predominance of postjunctional α2 adrenoceptors in digits of patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Increased Sympathetic Nervous System Activity

Although appealing as a potential mechanism for digital vasospasm, the concept of exaggerated reflex sympathetic vasoconstrictor responses to cold environment has not been convincingly demonstrated. Increased concentrations of epinephrine and norepinephrine in peripheral venous blood at the wrist were found to be higher in patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon than in normal subjects by one investigator,33 but others found normal local levels of norepinephrine in brachial arterial and venous blood samples.34 The latter group of investigators reported that the reflex vasoconstrictor response of the hand to a cold stimulus in affected patients is similar to that in a control group, and there were comparable vasoconstrictor responses to the intraarterial infusion of tyramine, a drug that causes vasoconstriction by releasing norepinephrine from sympathetic nerve terminals. Central thermoregulatory control of skin temperature has also been reported to be comparable in normal individuals and patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon.35 Finally, microelectrode recordings of skin sympathetic nerve activity do not demonstrate an abnormality in patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon.36 There was no hypersensitivity of the vessels to strong sympathetic stimuli or abnormal increase in sympathetic outflow.

β-Adrenergic Blockade

Raynaud’s phenomenon is observed frequently in individuals treated with β-adrenoceptor antagonists.37–39 It may be inferred from this observation that β-adrenergic vasodilation normally attenuates digital vasoconstrictor tone. Cohen and Coffman40 examined the effect of isoproterenol and propranolol on fingertip blood flow after vasoconstriction had been induced by a brachial artery infusion of norepinephrine or angiotensin, or reflexly by environmental cooling. Intraarterial isoproterenol administration increased fingertip blood flow during infusions of norepinephrine and angiotensin, but not during reflex sympathetic vasoconstriction. Conversely, propranolol served to potentiate vasoconstriction caused by intraarterial norepinephrine, but not that caused by reflex sympathetic vasoconstriction. These investigators concluded that a β-adrenergic vasodilator mechanism may be active in human digits, but does not modulate sympathetic vasoconstriction. There is no evidence to support the contention that decreased sensitivity or number of β adrenoceptors contributes to the pathophysiology of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the absence of pharmacological blockade of β adrenoceptors.

Vasoconstriction Caused by Circulating Vascular Smooth Muscle Agonists

The possibility that vasoconstrictors released during platelet aggregation may be pertinent to the pathophysiology of Raynaud’s phenomenon has been further evaluated by studies that have either measured levels of TxA2 or administered a thromboxane synthetase inhibitor.41,42 Coffman and Rasmussen compared the thromboxane synthetase inhibitor dazoxiben to placebo in patients with either primary or secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon.41 Dazoxiben did not affect total fingertip blood flow or fingertip capillary blood flow, whether measured in a warm (28.3 °C) or cool (20 °C) environment. With chronic treatment, there was a small decrease in frequency of vasospastic episodes in patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. To date, however, there is insufficient evidence to support a role for TxA2 in digital vasospasm.

Endothelin-1 is an endothelium-derived, powerful, and prolonged-acting vasoconstrictor agent suggested to play a part in the pathogenesis of Raynaud’s phenomenon. It rises in response to a cold pressor test and constricts cutaneous blood vessels.43 Studies measuring ET-1 in primary or secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon have been conflicting.44 Controlled clinical trials of ET-1 receptor antagonism in the treatment of Raynaud’s disease have achieved little success.45,46 It is therefore doubtful that it plays a role in Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Decreased Intravascular Pressure

Patency of a blood vessel requires balance between arterial wall tension (favoring closure of the vessel) and intravascular distending pressure. Landis measured intravascular pressure in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon by introducing a micropipette into a large digital capillary.47 During cyanosis, capillary pressure fell to approximately 5 mmHg, and flow ceased. These findings suggested that the site of closure was proximal to the capillaries at the arterial level. Interestingly, Thulesius reported that brachial artery blood pressure in patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon was significantly lower than that in a normal control population.48 Cohen and Coffman also found that blood pressure was lower in patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon compared with normal subjects.49 In addition to lower brachial blood pressure, systolic blood pressure (SBP) measured at the proximal and distal digital arteries averaged 18 mmHg less than that in normal digits.

Hyperviscosity may reduce blood flow velocity in digital vessels, leading to a decrease in intravascular pressure. Indeed, Raynaud’s phenomenon occurs in patients with hyperviscosity due to polycythemia vera or Waldenström macroglobulinemia.50,51 In patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to disorders such as cryoglobulinemia and cold agglutinin disease, hyperviscosity caused by cooling may contribute to digital vasospasm.52–54 Indeed, cooling has been shown to abolish hand blood flow in patients with cold agglutinins, possibly because the vessels become occluded by agglutinated red cells.54 Data invoking hyperviscosity as a cause of Raynaud’s phenomenon in patients who do not have an established blood dyscrasia, however, are less compelling.

Secondary Causes of Raynaud’s Phenomenon

The secondary causes of Raynaud’s phenomenon include collagen vascular diseases, arterial occlusive disorders, thoracic outlet syndrome, several neurological disorders, blood dyscrasias, trauma, and several drugs (see Box 48-1).

Collagen Vascular Diseases

Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma)

Several serological studies are consistent with the diagnosis of scleroderma. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be elevated, and ANAs are present in the majority of individuals with this disorder. Patients may have antibodies to nucleolar antigens, nuclear ribonucleoprotein, and to the centromeric region of metaphase chromosomes. In patients with systemic sclerosis and Raynaud’s phenomenon, capillary microscopy often demonstrates enlarged and deformed capillary loops surrounded by relatively avascular areas, particularly in the nailfolds.55 Angiography frequently demonstrates digital vascular obstruction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree