62 Quality of Care in Interventional Cardiology

Interventional cardiology has grown rapidly since its inception about 30 years ago. Invasive cardiovascular procedures have become a cornerstone for the evaluation and management of many cardiovascular diseases, especially coronary artery disease (CAD). Since these procedures are widely used, easily identified with claims data, and expensive, considerable attention has been focused on the cardiac cath lab. This attention has intensified in the present era because of increasing state and federal regulations, more frequent requests for the public reporting of hospital and physician data, consumer pressures for care of the highest quality, and increasing pressure from payers for care to be cost efficient with an increasing focus on ensuring the appropriate use of cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs). At the same time, there is a growing awareness that the quality of health care is compromised by several factors, including (1) preventable medical errors, (2) the absence of evidence-based standards in many areas, (3) a lack of emphasis on disease prevention, (4) inadequate personal responsibility for maintaining health, and (5) disparities in health care delivery related to race, gender, income, and insurance status. The desire to improve the quality of cardiovascular care was growing even before these recent trends in the health care marketplace and the focus on health care reform. Numerous government and private agencies in the United States have been involved in the development of quality measures and the dissemination of data for several years (Table 62-1). Statewide “report cards” on cardiac surgeries and PCIs for hospitals and individual physicians exist in some states.2,3 Interest in such reports on quality continues to increase as data have emerged showing that patients fail to receive up to 45% of the tests and treatments recommended by evidence-based guidelines.4 In an attempt to promote quality and improve outcomes, programs generally referred to as “pay-for-performance,” in which providers receive financial incentives for achieving certain benchmark goals in patient care, have been developed.5

TABLE 62-1 Organizations Involved in the Assessment of Quality Care

| Organization | Mission / Goals / Focus | Web Site |

|---|---|---|

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) | Lead Federal agency charged with improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of health care for all Americans | www.ahrq.gov |

| National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) | An initiative of AHRQ that is a public resource for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines | www.guideline.gov |

| Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) | Host site for Hospital Compare (www.hospitalcompare.hss.gov), a Web site that reports process of care, risk-adjusted outcome, and patient satisfaction measures for all hospitals in the United States | www.medicare.gov |

| Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) | Provides links to hundreds of sites on the Internet that contain reliable health care information and links to many government and nongovernment sources of information on healthcare quality | www.healthfinder.gov |

| The Joint Commission | Provides accreditation to hospital and other health care facilities; provides quality care and hospital quality measures for public reporting through the ORYX reporting program | www.jointcommission.org |

| National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) | A private, 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization dedicated to improving health care quality. Operate the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), a tool used by more than 90 percent of America’s health plans to measure performance on important dimensions of care and service | www.ncqa.org |

| The American Health Quality Association (AHQA) | An educational, not-for-profit national membership association dedicated to health care quality through community-based, independent quality evaluation and improvement programs | www.ahqa.org |

| National Quality Forum (NQF) | Sets national priorities and goals for performance improvement and endorses national consensus standards for measuring and publicly reporting on performance | www.qualityforum.org |

| American Medical Association (AMA) | Sponsored by the AMA, the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI) is committed to enhancing quality of care and patient safety by taking the lead in the development, testing, and maintenance of evidence-based clinical performance measures and measurement resources for physicians | www.ama-assn.org/ |

| American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) | In collaboration with other professional organizations develops clinical practice guidelines, expert consensus documents, and other quality programs including: Guidelines Applied in Practice (GAP) to provide assistance with guideline application in clinical practice and Hospital to Home (H2H), an effort to improve the transition from inpatient to outpatient status for individuals hospitalized with cardiovascular disease | www.cardiosource.org |

| American Heart Association (AHA) | In collaboration with other professional organizations develops clinical practice guidelines, expert consensus documents, and other quality programs including: Get With The Guidelines, a hospital-based quality improvement program designed to ensure that every patient is consistently treated according to the most recent evidence-based guidelines and Mission: Lifeline, a national, community-based initiative to improve systems of care for patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) | www.my.americanheart.org |

| The Leapfrog Group | A voluntary program organized by large employers to promote big leaps in healthcare safety, quality, and customer value. | www.leapfroggroup.org |

Although there are no formal national standards to judge the quality of cardiac cath labs, some states have used clinical practice guidelines and expert consensus documents published by the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) to develop quality standards.6–8 Although these documents were never intended to serve as state or national standards, they have often become the de facto basis for licensure regulations imposed by state health departments in an attempt to improve quality. To more completely understand the current status of quality efforts in the cardiac cath lab, it is helpful to examine some of the major events that form the history of quality efforts in U.S. health care.

A Brief History of Quality Efforts in U.S. Medicine

A Brief History of Quality Efforts in U.S. Medicine

Despite the many concerns about the state of American medicine today, there have been profound improvements during the past 150 years. The American Medical Association (AMA) was founded in 1847, in part, to address the disorganized and poor quality of health care in the United States. As a forerunner of efforts to come, in 1917, the American College of Surgeons established the Hospital Standardization Program promoting five minimal patient care standards and began surveying health care organizations to determine their acceptability for accreditation. On the basis of these early efforts, in 1952, several other organizations collaborated with the American College of Surgeons to form the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals.9 The U.S. concepts of quality in health care were advanced by Avedis Donabedian in 1966 with the publication of his classic article that provided a broad definition of quality and recommended evaluations in three areas: structure, process, and outcome.10 This format was widely adapted and is still in use today. During this early period, quality was often assessed by random chart audits or outcome-oriented chart surveys to evaluate metrics such as the use of blood products in surgical cases. Audit requirements were later minimized in favor of hospital-wide quality assurance programs designed to detect care that was felt to be outside acceptable standards. Physician profiles reflecting the number of procedures performed, indications, and complications were compared with grouped data from similar physicians to identify “outliers” with the hope that they might be induced to change their practice habits by colleagues, the hospital, or other agencies.11 Around 1990, a technique developed primarily for industry, called continuous quality improvement (CQI), was advocated by the Joint Commission. Compared with quality assurance programs, this approach tries to improve the performance of the entire group, rather than simply identifying poor performers.12–14 As quality efforts by the medical profession were maturing, state and federal agencies were also becoming interested in regulating health care, developing standards, and promoting high-quality medical care. By the late 1800s, many states required physician licensure and mandated educational standards for physicians. The National Board of Medical Examiners was founded in 1915 to provide a nationwide examination that licensing authorities could accept and use to judge candidates for licensure. As the medical field expanded and specialty training became available, it was recognized that some type of certification process for specialists was necessary. To establish a uniform system, the American Board of Medical Specialties was formed in 1933. There are now 24 specialty boards that certify physicians, and this process has evolved to one of continuous professional development and life-long learning through a Maintenance of Certification process requiring ongoing measurement of six core competencies.15 One of the first federal initiatives was the formation of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1906. With the enactment of Social Security in 1935, followed by Medicare in 1965, the Federal government became more involved in setting requirements for the delivery of health care funded by federal dollars. To monitor the care of Medicare patients, Congress enacted rules called Conditions of Participation, which required hospitals to provide certain services and conduct utilization reviews to determine the appropriateness of hospital admissions. In 1972, amendments to the Social Security Act created the Professional Standards Review Organization program to promote hospital efficiency and eliminate unnecessary hospital use. This program failed to meet expectations and was unpopular, as many felt it emphasized cost containment rather than quality.11 It was abandoned but was replaced by other peer review organizations (PROs).16 As this was evolving, substantial changes in hospital reimbursement occurred with a shift to a cost-per-case system based on assignment to a diagnosis-related group (DRG). The PROs were responsible for validating correct assignment to a DRG and also for monitoring hospital admissions, re-admissions, surgical procedures, complications, and hospital deaths. PROs emphasized quality but focused more on outcomes metrics rather than on structure and process metrics and so were not without their critics.17 Not surprisingly, as the amount of Medicare spending increased, the federal government became increasingly involved in monitoring and controlling payments to physicians and hospitals. Before 1989, physician payments for services within the Medicare program were based on usual and customary charges for services by similar physicians in the previous year. Substantial changes in Medicare payments to physicians occurred as a result of the Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989, which redirected payments based on costs rather than charges. Costs were determined for the actual work involved, the overhead required to provide the service, and malpractice costs, with all three elements further adjusted for geographic differences in cost. This caused major changes in practice patterns, which had both positive and negative effects on the quality of care. Additional federal funding led to the formation of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, which had a turbulent history and narrowly escaped being eliminated in 1995, only to be reauthorized in 1999 with a new mandate and name as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Many other quality initiatives and programs were developed by professional organizations and government agencies over the next 10 years with variable degrees of success. Now, several more are proposed as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPAHA-Public Law 111-148) of 2010. In addition to the sweeping changes in the delivery of health care, there are several provisions in this legislation specifically targeting the quality of health care. These include (1) establishment of a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, (2) formation of a Medicare Innovation Center with $10 billion to fund payment reform and quality improvement pilots, and (3) development of new systems linking payment to quality outcomes. These PPAHA and other progressive initiatives are aimed at ushering in substantial transformation of the American health care delivery system through the re-alignment of payment incentives rewarding quality rather than quantity of care.

Quality in Interventional Cardiology

Quality in Interventional Cardiology

The potential to deliver high-quality care in the cardiac cath lab centers on the core values promoted by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). In its report titled “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” quality is defined as “the degree to which health care systems, services, and supplies for individuals and populations increase the likelihood for desired health outcomes in a manner consistent with current professional knowledge.”19 The IOM further states that health care should be safe, effective, evidence based, timely, equitable, and patient centered. Several different definitions of quality have been proposed, reflecting the complexity of the health care system and its heterogeneous stakeholders. The Rand Institute defines quality care as “providing patients with appropriate services in a technically competent manner, with good communications, shared decision making, and cultural sensitivity.”20 An increasingly popular operational definition of quality is based on error reduction and the recognition that there are three major types of errors in health care: (1) underuse, (2) overuse, and (3) misuse.21 Underuse is defined as failure to provide a medical intervention when it is likely to produce a favorable outcome for a patient, such as the failure to prescribe lipid-lowering therapy for secondary prevention following a myocardial infarction (MI) in a patient with hyperlipidemia. Overuse is defined as the use of a test or therapy, even though its benefits do not justify the potential harm or costs, such as performance of a PCI in an asymptomatic patient with a stenosis of intermediate severity without first documenting the presence of important ischemia. Misuse occurs when a preventable complication eliminates the benefit of a therapy such as stent thrombosis because platelet inhibitors were not prescribed after placement of a coronary stent or when a stent is inadequately deployed in an artery and thus is not opposed to the vessel wall. Whatever definition of quality is used, there are several key elements that contribute to the development of quality health care.

Building Blocks of Quality in Health Care

Building Blocks of Quality in Health Care

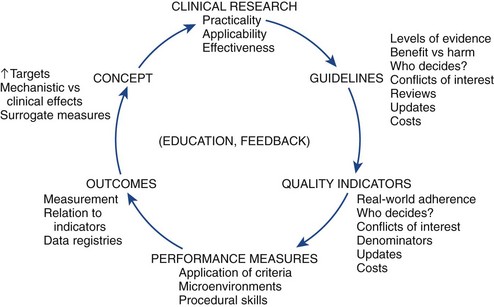

Fundamental to the development of a quality health care environment is the assurance that the patient is receiving the correct treatment for his or her condition. Obviously, if the patient receives flawless and efficient delivery of the wrong treatment for his or her condition, quality cannot exist. A model for the integration of quality into the cycle of therapeutic development has been proposed (Fig. 62-1).22 This starts with a hypothesis derived from the basic sciences, animal research, or other observations, progresses into early clinical research with small nonrandomized and unblinded case series, and eventually leads to a large randomized, blinded, and well-designed clinical trial. After one or more well-performed clinical trials provide clear information about a clinical question, the substrate is established for a clinical practice guideline.

Clinical Practice Guidelines

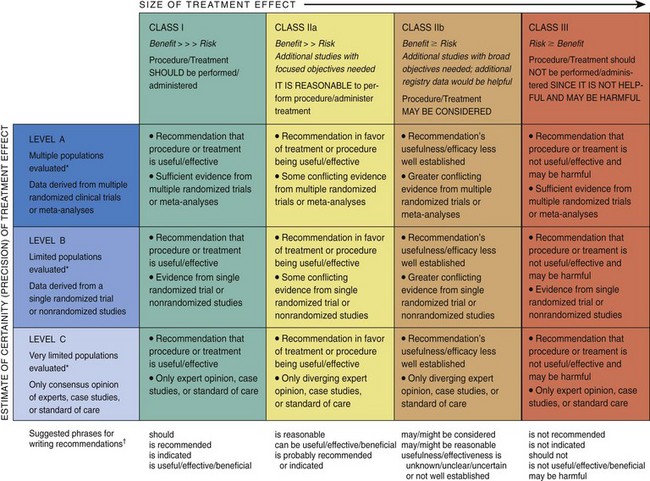

The IOM defines guidelines as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.”23 For nearly 20 years, the AHA and the ACCF, in conjunction with subspecialty organizations, where appropriate, have collaborated to develop clinical practice guidelines in cardiology. Guidelines have the potential to improve the quality of cardiovascular care and enhance the appropriateness of clinical practice, which, in turn, should lead to better patient outcomes, improved cost-effectiveness, and the identification of knowledge gaps that require further research. After a thorough review of all relevant evidence, guideline recommendations are developed with a level of evidence in a structured format (Fig. 62-2). To remain relevant and be embraced by clinicians, clinical practice guidelines must incorporate new evidence in a timely fashion; therefore, more focused guideline updates are now produced as new and important data are published. Recommendations contained within a guideline can be synthesized into algorithms, which then can be used to develop quality indicators, specifying the clinical circumstances under which a technology or treatment should or should not be used. In general, class I and III guideline recommendations with a level of evidence A identify recommendations that can be considered for the development of a quality measure. Unfortunately, the process is not as straightforward as it seems because of the many treatment considerations for which reasonable uncertainty exists. A challenging issue in the development of quality indicators occurs during the attempt to define which patients actually qualify for a particular indicator. In one study involving Medicare patients, less than half of all patients with an acute MI (AMI) actually qualified for a particular quality measure because of a long list of exclusions.24 If a large number of patients are excluded from a particular quality measure, the measure may not be a meaningful reflection of a physician’s or a facility’s care. Determining how well a provider or an institution meets specified quality indicators is one potential way to gauge the quality of the health care delivered.

Data Standards

A critical step for the success and application of quality standards is to have standardized data elements and corresponding definitions so that there is consistency in what is reported. For comparisons to be meaningful, there must be a common lexicon for describing the process and outcomes of clinical care, whether in randomized trials, observational studies, registries, or quality improvement initiatives. Particularly for quality performance measurement initiatives in which comparison of facilities or providers is proposed, common data standards and definitions must be clearly understood, consistently used, and properly interpreted by a broader audience for the entire process to be meaningful. To that end, the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards has undertaken the job of developing and publishing clinical data standards, data elements, and corresponding definitions that can be used in the assessment of patient management and outcomes and for research and epidemiologic assessments.25 Data standards have been developed for acute coronary syndromes (ACS), atrial fibrillation (AF), cardiac imaging, congestive heart failure (CHF), peripheral arterial disease (PAD), and electrophysiologic studies and are planned for several other topics.26 Cardiovascular data standards and their corresponding definitions then become the source for the data elements used in cardiovascular registries.

Performance Measures

Selecting performance measures involves evaluating the strength of evidence supporting the performance measure, defining the importance of the outcome most likely to be achieved by adherence to the performance measure, and assessing the association between adherence to the performance measure and a clinically important outcome. A detailed description of the methodology for the selection and creation of ACC/AHA performance measures has been published.27 Similar to quality measures, class I guideline recommendations identify potential patient care decisions that could be considered for a performance measure. Performance measures, in general, represent “must do” elements of clinical care, whereas failure to adhere to a performance measure represents inadequate or inferior care. Other important attributes to consider in the development of a performance measure are the cost associated with implementing the measure, availability of reimbursement for the therapy or intervention, and the cost of collecting data required for the measure (Table 62-2).

TABLE 62-2 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Attributes for Satisfactory Performance Measures

| Useful in improving patient outcomes |

| Measure design |

| Measure implementation |

(Adapted from Spertus JA, Eagle KA, Krumholtz HM, et al: American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association methodology for the selection and creation of performance measures for quantifying and quality of cardiovascular care, J Am Coll Cardiol 45(7):1147–1156, 2005.)

Performance measures also require that a threshold for acceptable performance be developed. This leads to questions regarding who determines the threshold and how the threshold level of performance is determined, as it is unlikely that 100% compliance will be achieved for every performance measure. One proposed method to define thresholds is to establish achievable benchmarks of care.28 Adherence to a performance measure is determined in a large sample and then the rate of adherence in the top 10% of facilities or physicians is set as the achievable benchmark. Using this method avoids establishing unreasonable goals which could paradoxically lead to inappropriate actions to achieve the established goal. Table 62-3 lists current performance measures related to cardiology and some additional measures under development. More recently, there has been interest in developing composite performance measures.29 A composite performance measure is the combination of two or more measures into a single index. Such composite measures reduce the information burden by distilling the available indicators into a simple summary that can examine multiple dimensions of provider performance and facilitate comparisons. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons has developed and validated a composite measure for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) consisting of five process measures and six outcome measures, all of which are endorsed by the National Quality Forum30,31 (Table 62-4). However, there are challenges to this approach. Details of an important individual measure can be diluted in the overall composite; methods for deriving the composite must be transparent to prevent it from being perceived as a black box.

TABLE 62-3 Current and Planned American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Performance Measure Sets

| Topic | Publication Date | Partnering Organizations |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic heart failure | 2005 | ACC/AHA: Inpatient measures ACC/AHA/PCPI Outpatient measures |

| Chronic stable coronary artery disease | 2005 | ACC/AHA/PCPI |

| Hypertension | 2005 | ACC/AHA/PCPI |

| ST and non-ST myocardial infarction | 2006 | ACC/AHA |

| Cardiac rehabilitation | 2007 | AACVPR/ACC/AHA |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2008 | ACC/AHA/PCPI |

| Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease | 2009 | ACCF/AHA |

| Peripheral artery disease | 2010 | ACCF/AHA/ACR/SCAI/SIR/SVM/SVN/SVS |

| Cardiac diagnostic imaging | 2011 | Planned |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 2011 | Planned |

ACC(F), American College of Cardiology (Foundation); AHA, American Heart Association; PCPI, American Medical Association—Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement; AACVPR, American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; ACR, American College of Radiology; SCAI, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; SIR, Society for Interventional Radiology; SVM, Society for Vascular Medicine; SVN, Society for Vascular Nursing; SVS, Society for Vascular Surgery.

TABLE 62-4 Individual Measures and Domains Included in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Composite Score

| Operative care domain |

| Perioperative medical care domain |

| Risk-adjusted mortality domain |

| Risk-adjusted major morbidity domain |

(From O’Brien SM, Shahian DM, DeLong ER, et al: Quality measurement in adult cardiac surgery: Part 2—Statistical considerations in composite measure scoring and provider rating, Ann Thorac Surg 83(4 Suppl):S13–S26, 2007.)

Real-World Impact of Performance Measures and Guidelines

With the goal to improve outcomes for patients with cardiovascular disease at the forefront of all the efforts described above, it is important to note that some studies do show a positive relationship between adherence to performance measures and clinical outcomes.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree