PVOD Medical Management

M. ASHRAF MANSOUR

Presentation

A 71-year-old man is sent to the vascular office by his Primary Care Physician because of absent pedal pulses and an abnormal CT of the chest that demonstrated a left subclavian stenosis. The patient is a former smoker (25 pack-years) with a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. He complains of bilateral calf cramping when walking, especially on an incline. He does not have any arm symptoms or dizziness with head turning. He denies angina with exertion. He denies rest pain or ulcers on the feet. He does have mild dyspnea with exertion.

Differential Diagnosis

Patients who complain of intermittent claudication, described as a cramp-like feeling in the calf that starts after walking and subsides with rest, should be suspected of having peripheral vascular occlusive disease (PVOD). It is important to ask if the symptoms are unilateral or bilateral. Patients with the classic risk factors for PVOD, including smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, will invariably have either aortoiliac or femoropopliteal occlusive disease. Other less common vascular conditions include thrombosed popliteal aneurysm, popliteal entrapment, or cystic adventitial disease of the popliteal artery. Nonvascular conditions mimicking claudication include neurogenic claudication (compression of lumbar nerves) and venous claudication (due to iliac vein stenosis or occlusion).

Workup

A good clinician can identify many clues about the location and extent of PVOD. For example, a diminished femoral pulse leads to a suspicion for iliac occlusive disease.

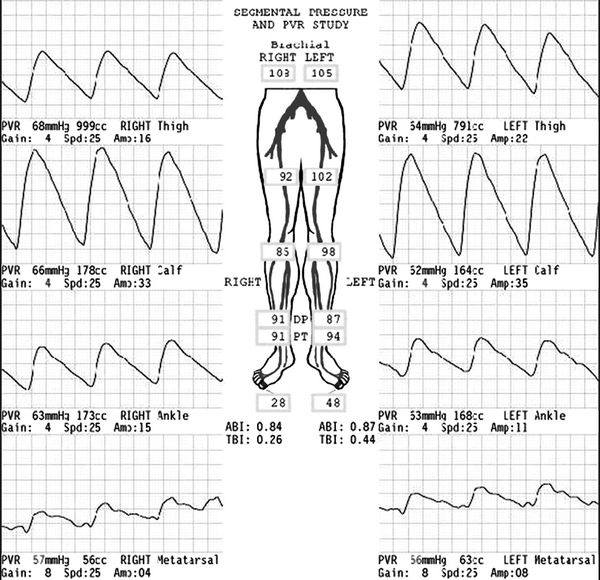

A complete physical examination should include palpation of all the peripheral pulses. An ankle-brachial index (ABI) should be obtained in the office, ideally with segmental arterial pressures and waveforms (Fig. 1). In some vascular laboratories, an arterial duplex mapping can be performed to image the lower extremity arterial tree. This is time consuming and requires a proficient vascular technologist performing the test.

FIGURE 1 Segmental arterial pressures and pulse volume recordings from a patient with mild claudication. Normal ABI is >0.94. This test suggests mild femoropopliteal occlu- sive disease.

More invasive imaging, such as computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), will require intravenous administration of contrast material (Isovue for CTA and gadolinium for MRA) both of which are contraindicated in patients with renal insufficiency. Digital subtraction angiography is also invasive since it involves intra-arterial injection of contrast and imaging in a Cath Lab or Endovascular Suite. In general, more invasive studies are obtained in cases where some intervention is being planned and not as screening tests.

Discussion

Claudication due to PVOD is a very common vascular problem. It is estimated that 10 to 12 million individuals in the United States suffer from claudication. There are many risk factors that contribute to PVOD, and they include tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. The clinician who evaluates a patient with claudication must consider the patient as a whole, including the medical management of risk factors, and decide on the goals of therapy. It is unlikely that an elderly, obese patient with a sedentary life style will benefit significantly from an intervention aimed at improving the ABI.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The diagnosis of PVOD is established when the clinical findings on physical examination and noninvasive testing correlate with the patient’s symptoms. With the widespread use of CTA, there are many patients who have evidence of PVOD but are not particularly symptomatic. Conversely, a patient may present with classic symptoms of calf claudication, and yet palpable pedal pulses are present on exam. In the latter case, an exercise stress test is needed to confirm the diagnosis. If the ABIs are normal at rest, drop with treadmill walking, and return to baseline after a period of rest, the test is considered positive. Conversely, if the ABIs do not drop with walking, the test is considered negative.

The management of PVOD depends on the severity of symptoms and the disease. For example, a patient presenting with toe gangrene will require a more aggressive and urgent approach compared to a patient with three- to four-block calf claudication. In general, the management of PVOD will involve one or more of these three broad categories: medical, endovascular, and surgical management.

Medical Management

In most vascular patients, atherosclerotic changes are not confined to the peripheral vascular circulation. In fact, PVOD is a marker for cardiovascular complications (such as stroke and myocardial infarction) and death. Therefore, it is important to initiate medical management of all patients with PVOD (regardless of whether or not an intervention is planned). The cornerstone is primarily risk factor modification and counseling for a healthier lifestyle.

Risk factor modification includes smoking cessation, controlling hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. Using an ACE inhibitor and lipid-lowering agents has been found to be beneficial to patients with PVOD. Similarly, aspirin (80 to 100 mg) daily is beneficial. The specific goals of medical management include maintaining a blood pressure of less than 140/90 mm Hg, LDL cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL (although newer guidelines suggest not necessarily treating to a goal reduction), and hemoglobin A1c < 7.0%.

Cilostazol (Pletal) is a drug that has been approved for the treatment of intermittent claudication. It acts by a dual mechanism of platelet inhibition and peripheral vasodilation; it is a phosphodiesterase III inhibitor. However, this agent cannot be used in those with low ejection fractions (EF less than 30%) or with a history of Congestive Heart Failure.

In addition to prescribing medications, the physician should counsel patients to lose weight, adopt a Mediterranean diet, exercise regularly, and embrace a generally healthier lifestyle, although the evidence that these changes affect PVOD progression is lacking.

Long-Term Management

As previously mentioned, the long-term goals of treating patients with PVOD are to improve their symptoms and decrease the risk of cardiovascular complications, including myocardial infarction and stroke, and limb loss. It is paramount to convince patients that they need to adopt a healthy lifestyle and shun bad habits, such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and a fatty diet. Indeed, smoking cessation is one of the most important changes a patient can make. Many studies have shown that regular supervised exercise, daily walking, can significantly improve the symptoms of PVOD. With a proper exercise regimen, patients are able to increase their walking distance and generally feel better.

Case Conclusion

The patient started a regular walking program with the help of his wife, with a goal to walk for 25 minutes at least five times a week. Cilostazol was started. At 3 months, the patient reported significant relief of his symptoms.