Pulmonary Vasculitis

NOMENCLATURE AND DEFINITIONS

Pulmonary vasculitis is usually a manifestation of a systemic disorder leading to inflammation of vessels of different sizes by a variety of immunological mechanisms. Vasculitis can be categorized into primary vasculitis and secondary vasculitis. The primary systemic vasculitides are a heterogeneous group of syndromes of unknown etiology, which share a clinical response to immunosuppressive therapy (Table 74-1). Their wide spectrum of frequently overlapping clinical manifestations is defined by the size and location of the affected vessels as well as the nature of the inflammatory infiltrate. Secondary vasculitis may represent significant management problems in the context of a well-defined underlying disorder, such as diffuse alveolar hemorrhage caused by systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Alternatively, secondary vasculitis may be an incidental histopathological finding, for instance, in the context of an infection or necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis.

Classification schemes and definitions of the various forms of vasculitis have evolved over the past decades. Historically, the classification of the vasculitis has been based on the size of the most prominently affected vessels. The primary purpose of classification and nomenclature is to standardize communication between clinicians and investigators and to facilitate more uniform treatment approaches. Ideally, they reflect the current understanding of pathogenesis. The first international consensus conference on the nomenclature of systemic vasculitides held in 1992 in Chapel Hill aimed to reconcile definitions and classification schemes used by European and American investigators. The resulting nomenclature and definitions were based mainly on histopathological criteria, particularly the size of the vessels involved, but allowed for radiographic and clinical surrogates to fulfill the definitions. These definitions, nomenclature, and classification found wide acceptance. The terminology was recently revised and updated at the second 2012 Chapel Hill International Consensus Conference so that it reflects novel insights into the pathogenesis of various vasculitides while avoiding the use of eponyms as much as possible.1 In this chapter, the specific definition of each form of vasculitis is discussed in detail as part of the description of the clinical manifestations and differential diagnosis of each entity.

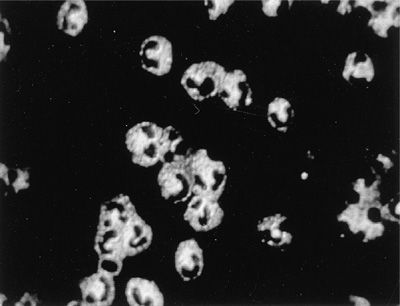

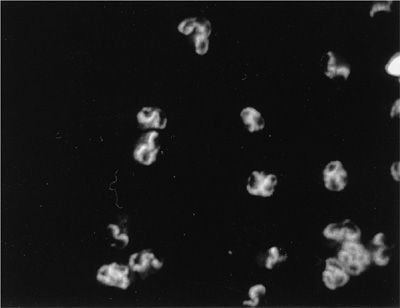

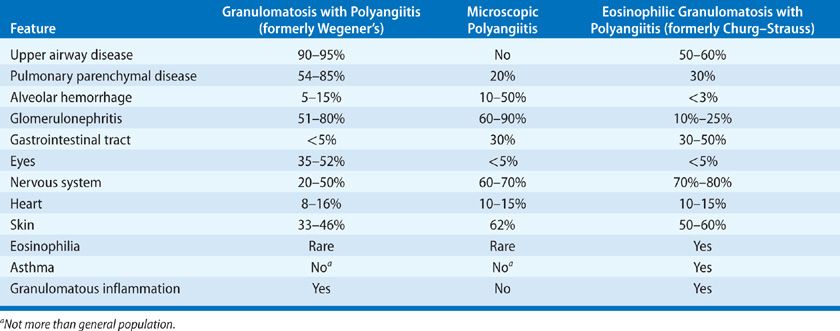

The 2012 Chapel Hill nomenclature is clinically very useful to pulmonologists as it reflects the clinical and histopathological pulmonary features and facilitates the therapeutic approach to individual patients. The three small vessel vasculitides that present most often with respiratory symptoms are granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA [formerly Wegener granulomatosis]), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA [formerly Churg–Strauss syndrome]). Most patients with these syndromes have antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA) detectable in the serum at the time of initial presentation.2 Consequently, this group of small vessel vasculitides is referred to in cumulo as “ANCA-associated vasculitis.” In patients with vasculitis, two types of ANCA are of clinical significance. In more than 80% of patients with GPA (Fig. 74-1), ANCA occur and are associated with a cytoplasmic immunofluorescence pattern (C-ANCA) on ethanol-fixed neutrophils that react with the neutrophil granule enzyme, proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA). In contrast, ANCA that cause a perinuclear immunofluorescence pattern (P-ANCA) on ethanol-fixed neutrophils and react with myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA) occur in fewer than 10% of patients with GPA but in the majority of patients with MPA (Fig. 74-2). MPO-ANCA are also the predominant type of ANCA encountered in patients with EGPA, in which PR3-ANCA are the exception. Despite these circulating autoantibodies, hardly any immunoglobulin deposits can be detected in the tissue lesions of ANCA-associated vasculitis, and they are consequently called “pauci-immune” lesions.

Figure 74-1 Cytoplasmic indirect immunofluorescence (C-ANCA) pattern in ethanol-fixed neutrophils caused by ANCA reacting with PR3.

Figure 74-2 Perinuclear indirect immunofluorescence (P-ANCA) pattern in ethanol-fixed neutrophils caused by ANCA reacting with MPO.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The primary systemic vasculitides are rare and few epidemiological studies have been conducted, mostly in ethnically homogeneous populations.3 Giant cell arteritis is the most frequent form of systemic vasculitis with an annual incidence of 13 per million adults (40 per million over the age of 60). It appears to be increasing in frequency and becoming cyclical over time. The latter observation has been interpreted as possibly suggesting a relationship with infections. Respiratory manifestations rarely represent significant management problems in these patients. Various studies from different regions of the world report a fairly uniform annual incidence of one to two cases per million for Takayasu arteritis. Pulmonary vascular complications occur in about half of the afflicted patients. The estimated annual incidence of GPA has been rising over the decades from 0.5 to 0.7 per million during the 1970s and early 1980s to current estimates of about 10 to 12 per million. Similar increases in annual incidence have been observed for MPA and EGPA. The average frequency of MPA is similar to that of GPA; for EGPA it is estimated to be of the order of one to three per million. The ANCA-associated vasculitides have different ethnic predilections: GPA affects predominantly whites, and northern Europeans appear more prone to develop GPA. In contrast, individuals of southern European and Mediterranean descent appear to be relatively more apt to develop MPA. GPA and MPA can affect individuals of any age. However, the incidence of GPA plateaus after age 50, whereas the likelihood of developing MPA continues to increase with age.

The annual incidence of the secondary vasculitides varies widely. The reported frequencies for rheumatoid vasculitis and vasculitis in SLE are 12.5 per million and 3.6 per million, respectively. Behçet disease has a peculiar geographic distribution along the old Silk Road, with the highest prevalence being reported from Turkey, Central and far eastern Asia, where the frequencies range from 100 to 380 per 100,000, compared with only 1 per 100,000 in western Europe.

The available population-based studies need to be interpreted with some caution because they do not distinguish between whether the observed increased incidence of systemic vasculitis is true, or the result of more frequent recognition of the disease. Moreover, whether individual diagnoses are accurate and consistent is challenged by the changing definitions of the syndromes over time.

ANCA-ASSOCIATED VASCULITIS

The ANCA-associated vasculitides include granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. The clinical presentation, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment of these entities are discussed below.

GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS: CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS: CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

GPA is the most common form of vasculitis to involve the lung. The Chapel Hill Consensus Conference defined GPA as “necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the respiratory tract, and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.”1 However, it is important to recognize that GPA is a systemic disease that can affect almost any organ (Table 74-2). The most frequently involved sites are the upper airways, lungs, and kidneys.4 Symptoms and clinical disease manifestations are the result of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and small vessel vasculitis that occur in variable degrees of combination.

In the 1960s the term “limited Wegener granulomatosis” was introduced to indicate patients with GPA who lacked renal disease. The use of this term and its implications have evolved over the last two decades. Even in the absence of renal involvement, patients may have life-threatening pulmonary or neurological disease requiring aggressive immunosuppressive treatment. For instance, a patient who “only” has alveolar hemorrhage in the absence of glomerulonephritis should never be classified as having “limited” GPA. Consequently, today, the use of the term “limited GPA” implies that (a) the pathology is predominantly a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation, and the vasculitis seen on biopsy is of lesser clinical significance; and (b) there is no immediate threat either to the patient’s life or that the affected organ is at risk for irreversible damage. In this sense, the terms “limited” or “nonsevere” GPA are now used interchangeably as distinction from “severe” GPA, which by definition either threatens the patient’s life (alveolar hemorrhage) or a vital organ with the risk of irreversible damage (rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, scleritis, or mononeuritis multiplex). These definitions and distinctions form the basis for stratification of current standard therapy.

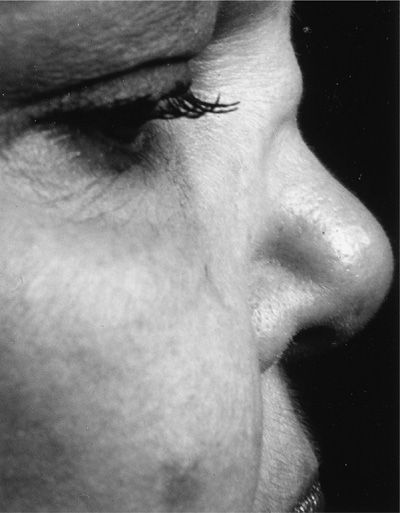

Over 90% of patients with GPA first seek medical attention for symptoms arising from either the upper and/or lower airway. Nasal and sinus disease is characterized by congestion and epistaxis due to mucosal friability, ulceration, and thickening. Patients may also have features of chronic sinusitis and recurrent or chronic serous otitis. Perforation of the nasal septum and/or saddle nose deformity may result from ischemia of the nasal cartilage (Fig. 74-3). Oral manifestations include gingival hyperplasia (Fig. 74-4) and oropharyngeal ulcerations. Subglottic stenosis occurs in approximately 20% of patients and can cause life-threatening compromise of the airway. Subglottic stenosis may occur in the absence of other features of active GPA, and its symptoms may be nonspecific, for example, dyspnea, hoarseness, cough or stridor; the latter is occasionally mistaken for wheezing.

Figure 74-3 Saddle nose deformity of granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Figure 74-4 Strawberry or mulberry gums in a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

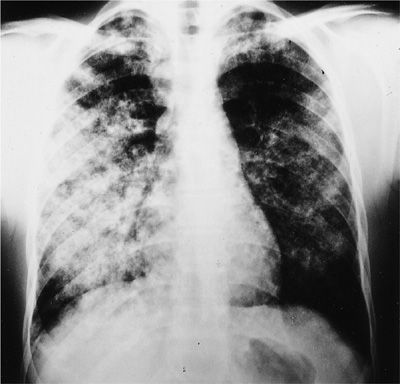

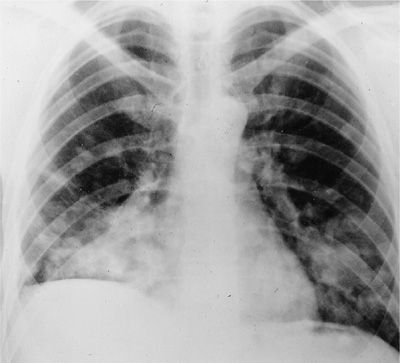

GPA involving the lower airways can affect the pulmonary parenchyma, the bronchi, and rarely the pleura. Presenting features of parenchymal involvement may include cough, dyspnea, chest pain, or hemoptysis. However, some patients may be completely asymptomatic. Patients with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage usually present with progressive dyspnea and anemia (Fig. 74-5). Hemoptysis is absent in about one-third of patients. Patients with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage may deteriorate rapidly and experience respiratory failure, which has a mortality rate up to 50%.

Figure 74-5 Chest radiograph of a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis displaying an alveolar filling pattern indicative of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

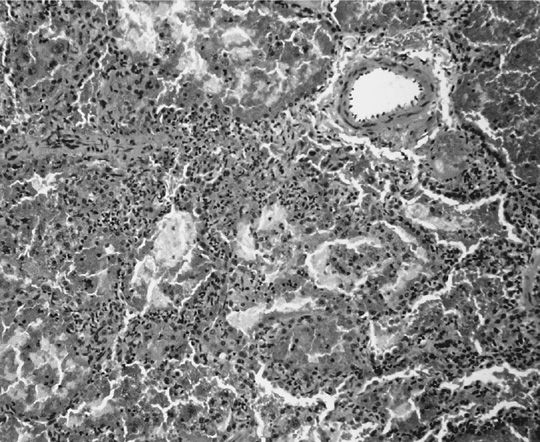

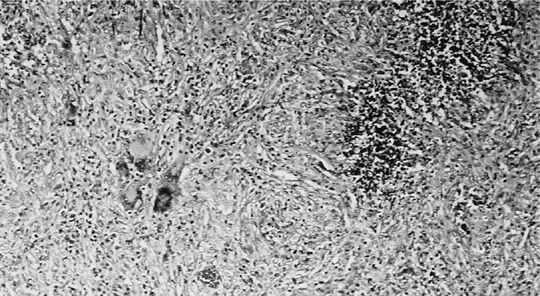

The clinical presentation of alveolar hemorrhage is caused by pulmonary capillaritis (Fig. 74-6). The predominant inflammatory cells are neutrophils. However, eosinophils or monocytes may also be present. Capillaritis usually causes fibrinoid necrosis of alveolar and vessel walls and may culminate in the destruction of the underlying architecture of the lung. An important hallmark of capillaritis is the presence of pyknotic cells and nuclear fragments from neutrophils undergoing apoptosis, a feature called leukocytoclasis. This hallmark enables distinction between true capillaritis and margination of neutrophils related to surgical trauma. Depending on the acuteness and duration of alveolar hemorrhage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages and interstitial hemosiderin deposits may be present.

Figure 74-6 Alveolar capillaritis causing pulmonary hemorrhage in granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

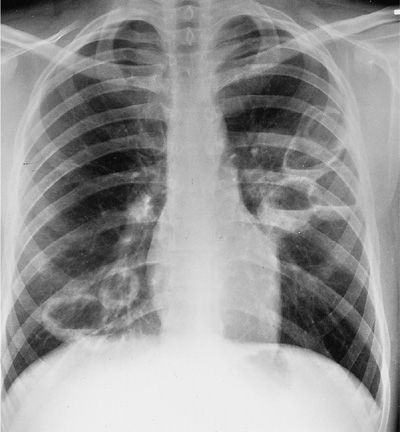

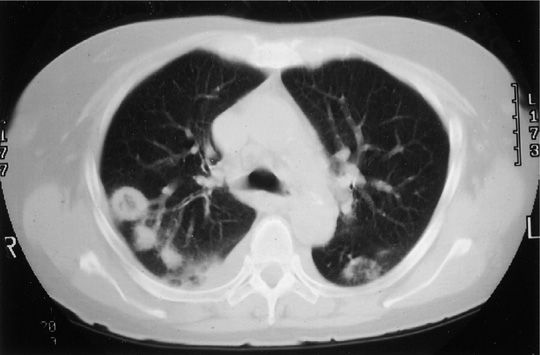

The most common form of pulmonary involvement in GPA is caused by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and presents radiographically as nodules or mass lesions, which may cavitate (Figs. 74-7–74-9). These lesions may be incidental findings on thoracic imaging studies as they cause little symptoms and do not result in significant abnormalities of pulmonary function. Prominent air–fluid levels can be seen when the necrotic center of the inflammatory lesion gets superinfected (Fig. 74-8). These necrotizing granulomatous lesions are a disease-defining feature of GPA. Their presence easily separates GPA from MPA. In the absence of other features of small vessel vasculitis in other organs, the differential diagnosis of these lesions consists primarily of infections, particularly caused by fungal or mycobacterial organisms, and less likely of malignancies or necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis.

Figure 74-7 Chest radiograph of a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis displaying multiple nodules with and without cavitation.

Figure 74-8 Chest radiograph of a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis showing multiple large cavities, some with air–fluid levels.

Figure 74-9 Computed tomography scan of a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis showing multiple nodules, some with cavitation. There are also small bilateral pleural effusions.

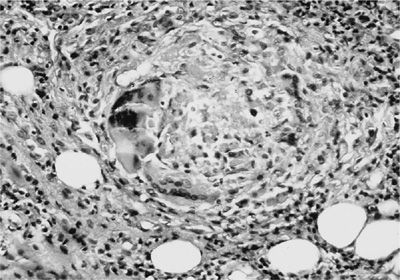

The lung nodules of GPA have very characteristic histopathological features. Small necrotizing microabscesses appear to be the earliest lesion. They enlarge and coalesce until the typical geographic and basophilic appearance of the necrosis has developed (Fig. 74-10). The necrotic center is surrounded by palisading histiocytes and scattered giant cells. Occasionally the necrosis may be bronchocentric. When this type of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation extends into the walls of small vessels it is referred to as granulomatous vasculitis (Fig. 74-11). In contrast to capillaritis, this type of vasculitis seems to be a secondary phenomenon of the necrotizing granulomatous inflammation affecting the lung parenchyma. The inflammatory background of the granulomatous necrosis and vasculitis consists of a mixed cellular infiltrate containing lymphocytes, plasma cells, scattered giant cells, and eosinophils. It may cause extensive parenchymal consolidation mimicking organizing pneumonia. Well-defined sarcoid-like nonnecrotizing granulomas are not found in GPA.

Figure 74-10 Geographic basophilic necrosis with palisading histiocytes and giant cells from a lung nodule in a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Figure 74-11 Granulomatous vasculitis with giant cells in a lung biopsy of a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Inflammation and stenosis of the tracheobronchial tree occur in at least 15% of patients with lung involvement.5,6 Endobronchial disease may be an incidental finding on bronchoscopy or present with cough, hemoptysis, wheezing, dyspnea, or symptoms related to parenchymal collapse or postobstructive infection. Spirometry including inspiratory and expiratory flow–volume loops may show characteristic abnormalities indicative of degree and location of airway narrowing. Subglottic stenosis represents a fixed airway obstruction resulting in flattening of both the inspiratory and expiratory loops. If the intrathoracic trachea, or more commonly, one or both mainstem bronchi are affected, flattening of the expiratory curve can be found. Pleural effusions may occur, but are usually small, asymptomatic, and incidental findings (Fig. 74-9). Other thoracic manifestations of GPA include inflammatory pleural pseudotumors or hilar adenopathy. The latter should raise the suspicion of infection, sarcoidosis, or lymphoma.

Glomerulonephritis is among the most concerning disease manifestations of GPA as it can progress to complete renal failure in the absence of symptoms. It is usually detected by the presence of abnormal laboratory results such as active urine sediment with microscopic hematuria and red cell casts, proteinuria, and declining renal function. Continued vigilance for glomerulonephritis is essential as it is present at diagnosis in less than half of all patients. However, over the course of their disease, the kidneys are affected in 80% of patients.

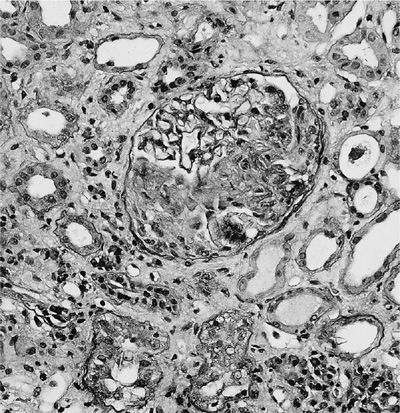

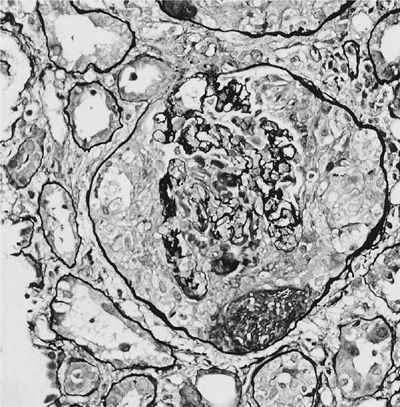

A renal biopsy is useful to establish a diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis and to determine the renal prognosis. The glomeruli are not affected uniformly (focal) by segmental, necrotizing inflammation (Fig. 74-12), and cellular crescents (Fig. 74-13) are frequently found. The number of glomeruli affected, degree of crescent formation, and destruction of individual glomeruli as well as the amount of sclerosis found determine the chance of recovery of renal function. In addition, tubular fibrosis and atrophy affect renal outcomes. Direct immunofluorescence reveals no or only scant immune deposits (pauci-immune glomerulonephritis). Granulomatous inflammation affecting the renal parenchyma and tubulointerstitial nephritis can also be found rarely.

Figure 74-12 Focal necrotizing glomerulitis of granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Figure 74-13 Rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis in granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

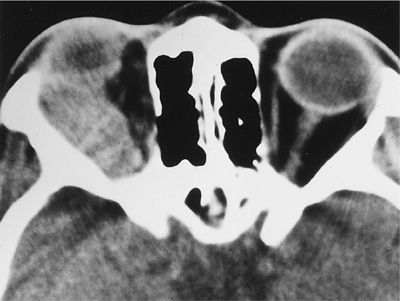

A wide spectrum of ocular manifestations has been observed in GPA, which may threaten vision by affecting the eye directly or involving its contiguous structures. Manifestations may include conjunctivitis, episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis, corneal ulceration, uveitis, and retinal vasculitis. Involvement of the lacrimal system may result in epiphora, dacryocystitis, and fistula. Retro-orbital inflammatory pseudotumors may affect one or both the eyes, threaten the vision, and represent the most difficult challenge in the management of GPA (Figs. 74-14 and 74-15). Any patient with GPA who presents with eye pain or redness, proptosis, change in visual acuity, diplopia, or loss of visual field should be referred for emergent ophthalmological consultation.

Figure 74-14 External ophthalmoplegia of the left eye due to orbital involvement with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Figure 74-15 Computed tomography scan of the orbits in a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis showing a mass in the right orbit causing external ophthalmoplegia.

Nervous system involvement may occur in up to one-third of patients. Mononeuritis multiplex of the peripheral nervous system caused by inflammation of the vasa nervorum as well as central nervous system vasculitis and pachymeningitis represent severe disease manifestations with substantial risk of irreversible damage, persisting even after the acute inflammation is adequately controlled.

Cardiac involvement may be occult. Regional wall motion abnormalities with a noncoronary distribution pattern are frequent echocardiographic findings.7 It is unclear whether this type of cardiomyopathy is the result of small vessel disease or inflammatory infiltration of the cardiac muscle. Pericarditis, valvulitis, and inflammatory pseudotumor have also been described.

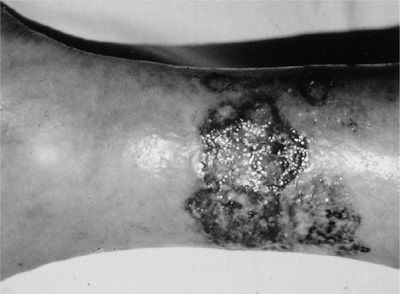

A wide spectrum of cutaneous manifestations may be observed in GPA. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis presenting as palpable purpura is most common, followed by pyoderma gangrenosum–like lesions (Fig. 74-16) and so-called Churg–Strauss granulomas.

Figure 74-16 Pyoderma gangrenosum of the leg in a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

MICROSCOPIC POLYANGIITIS: CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

MICROSCOPIC POLYANGIITIS: CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

Histopathologically, the necrotizing small vessel vasculitis of MPA causing necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis and pulmonary capillaritis is indistinguishable from that encountered in GPA.8 Consequently, there is substantial overlap in organ manifestations and symptoms between the two syndromes (Table 74-2). A timely diagnosis of MPA may be delayed by a gradual onset or the nonspecific nature of symptoms such as fever, malaise, and weight loss. All organ systems may be involved. The kidneys are most commonly affected in up to 80% of patients. Other commonly encountered disease manifestations include diffuse alveolar hemorrhage due to pulmonary capillaritis affecting 10% to 30% of patients. MPA is the most frequent cause of pulmonary renal syndrome. Several cases of MPA in association with severe obstructive airway disease or bronchiectasis have also been described. More recently, several case series have highlighted an association between usual interstitial pneumonia and MPO-ANCA–positive MPA. In these cases, the fibrotic changes either precede the development of MPA or are already present at the time of diagnosis of MPA.

Palpable purpura caused by leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the skin, and musculoskeletal complaints, such as arthralgias and myalgias, are also common. Gastrointestinal involvement occurs in about one-third of patients. This is in contrast to GPA, in which gastrointestinal involvement is very rare. Visceral angiography is generally not helpful for the evaluation of abdominal symptoms as the vessels involved are too small to be visualized. CT with or without contrast injection may be more helpful if gastrointestinal involvement is suspected. However, the use of contrast is relatively contraindicated in patients with active renal involvement. Sinusitis and asthma are rarely found in MPA, and should lead to the consideration of an alternative diagnosis.

Most patients with MPA have ANCA, and in 40% to 80% they are of the P-ANCA variety, reacting with MPO. C-ANCA reacting with PR3 is seen less frequently. Occasionally patients with MPA later develop granulomatous inflammation and are reclassified as having GPA; this is more likely to occur in patients with C-ANCA.

As in GPA, a histopathological diagnosis may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis before the patient is committed to prolonged immunosuppressive therapy. The biopsy specimen should be sought from the most accessible site. Renal biopsy shows pauci-immune focal segmental–necrotizing glomerulonephritis, with extracapillary proliferation forming crescents. In contrast to GPA, granulomatous inflammation is not a feature of MPA. All other histopathological features are indistinguishable from those of GPA. Treatment of MPA should follow the principles applied to the management of GPA. Consequently, most cases of MPA require immunosuppressive therapy used for patients with severe GPA.

EOSINOPHILIC GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS: CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

EOSINOPHILIC GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS: CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

EGPA is the third type of vasculitis that commonly affects the lung. The 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus definition for the disease is “eosinophil-rich and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation often involving the respiratory, and necrotizing vasculitis predominantly affecting small- to medium-sized vessels, and associated with asthma and eosinophilia.”1 EGPA is included among the ANCA-associated vasculitides even though only 40% to 70% of patients with active EGPA are ANCA positive.9–11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree