Pulmonary Sarcomas

Jennifer M. Boland, M.D.

Eunhee S. Yi, M.D.

Fabio R. Tavora, M.D., Ph.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Overview and Terminology

Pulmonary sarcomas are rare, and comprise tumors that arise from the parenchyma and those that occur within the pulmonary arteries (intimal sarcomas). Parenchymal sarcomas are most frequently, synovial sarcomas, epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas (EHEs) leiomyosarcomas, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.1 Other sarcomas that have rarely been reported to involve the lung include undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (previously malignant fibrous histiocytoma),2 liposarcoma,3,4 and rhabdomyosarcoma.5,6

Although there is overlap, mesenchymal tumors that more frequently involve the pleura than the parenchyma, including solitary fibrous tumor, synovial sarcoma, and angiosarcoma, are presented in Chapter 96.

Pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) and primary pulmonary myxoid sarcoma (PPMS) are rare sarcomas unique to the lung parenchyma and are also discussed in this chapter.

Leiomyosarcoma

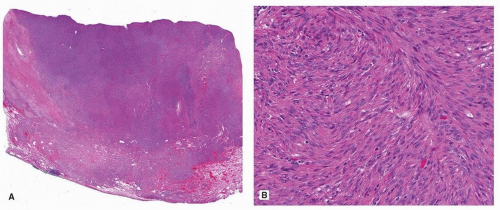

Pulmonary leiomyosarcoma is rare and is diagnosed only after a metastatic tumor from an occult primary site is excluded. These tumors occur in adults of both sexes, but there may be a male predominance.1 Parenchymal leiomyosarcoma should be considered separately from intimal sarcomas with leiomyosarcomatous differentiation and those rare tumors that arise in the bronchi.7 The diagnosis can be obtained by surgical resection or endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle biopsy.8 Grossly, parenchymal leiomyosarcomas are large, fleshy tumors that are typically larger than 10 cm.1 Histologically, pulmonary leiomyosarcomas are similar to those arising in soft tissue (Fig. 93.1). Prognosis is poor,1 although long-term survival has been reported.9

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma

In the lung, EHE formerly went by the name intravascular bronchioloalveolar tumor (IVBAT), but this term is outdated and should no longer be used.10

Clinical Findings

Pulmonary EHE has a predilection for adult females and tends to involve the lung in a multifocal fashion (multiple bilateral nodules < 2 cm, often pleural based).11,12 The observed age range is wide, spanning children to the elderly, but most patients are middle aged (third to fifth decade of life). Clinical and radiographic findings may suggest metastatic disease involving the lung or old granulomatous disease. However, unusual presentations have been well documented, including a solitary pulmonary nodule, diffuse pleural thickening simulating mesothelioma, and lymphatic distribution mimicking lymphangitic carcinoma.13 The three most commonly observed radiographic patterns include multiple pulmonary nodules, multiple pulmonary reticulonodular opacities, or diffuse infiltrative pleural thickening.14 Most patients are asymptomatic at the time of presentation, but some will have localizing symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis, pain, or pleural effusion.11

Pathologic Features

Pulmonary EHE usually appear as circumscribed firm gray-white nodules that may have a chondroid or mucoid cut surface. Some tumors with extensive pleural involvement may alternatively show diffuse pleural thickening.10 Whether cases of EHE presenting bilaterally in the lungs without an obviously primary site elsewhere may represent metastases from an occult primary remains unclear.10

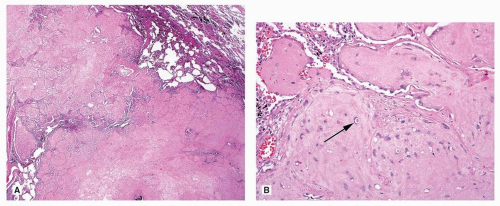

The nodules of pulmonary EHE often have central hyalinization or necrosis with accentuation of cellularity at the periphery of the nodule. The tumor is often associated with vascular structures (arteries, veins, or lymphatics) and often shows intravascular growth. The pleura is often involved and diffusely thickened. The combination of vascular and pleural involvement leads to a lymphangitic growth pattern in many cases.

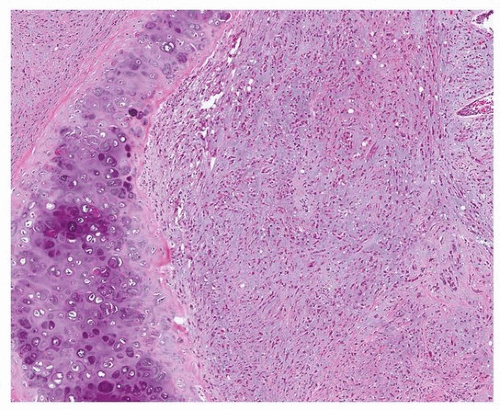

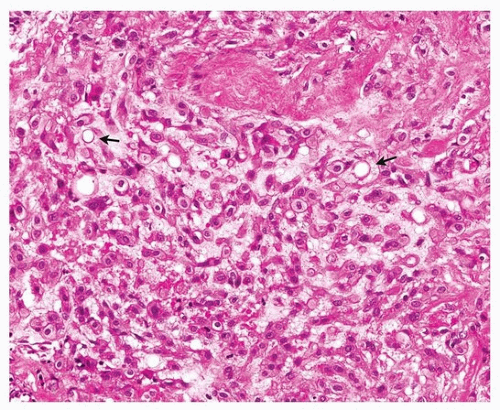

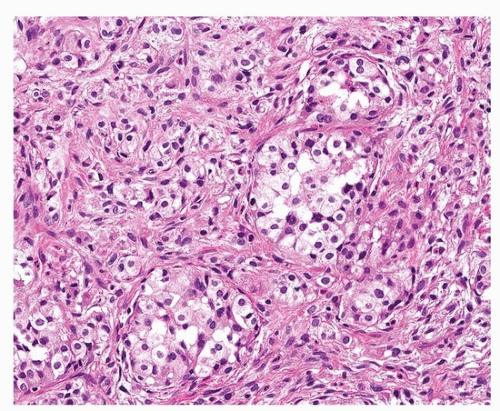

Bland epithelioid endothelial cells grow in chains and cords and are dispersed in a myxohyaline or myxochondroid matrix (Figs. 93.2, 93.3, 93.4, 93.5). Scattered EHE cells will have intracytoplasmic vacuoles/vascular lumens, which may contain an erythrocyte (often fragmented), but EHE cells typically do not form extracellular vascular structures.15 Intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions have also been noted frequently in EHE.10 In the lung, EHE tends to show a “micropolypoid” growth pattern, showing protrusion into bronchioles and alveolar spaces, often with little or no apparent reactive response in the alveolar septa. Most “classic” EHEs have bland, low-grade cytology, but some examples may show atypical/intermediate-grade features including moderate pleomorphism, increased cellularity, and necrosis, which may correlate with a more aggressive behavior.10

FIGURE 93.3 ▲ Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. There are cords of cells with abundant pink cytoplasm and occasional vacuoles (arrows). |

EHEs typically express a variety of vascular endothelial markers including CD31, ERG, Fli1, and CD34, but CD31 and ERG may be the most sensitive for pulmonary EHE.10 EHEs also commonly express low molecular weight cytokeratin or EMA (25% to 40% of cases), which is a potential diagnostic pitfall.10 EHEs have recently been discovered to harbor a recurrent t(1;3)(p36;q23-25), resulting in the WWTR1–CAMTA1 fusion gene in the majority of cases.10,16,17

FIGURE 93.4 ▲ Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. A nested pattern resembling carcinoid tumor may occur. |

Some EHEs seem to lack this fusion gene, so negative genetic testing, which is not necessary in typical cases, does not exclude the diagnosis.10

Prognosis

EHE is generally an indolent tumor, but distant metastases will occur in around 20% to 30% of cases, and 5-year survival is around 60%.18 Patients with pulmonary EHE who present with clinical symptoms or with extensive involvement of bronchioles, vascular structures, and pleura seem to have a worse outcome.10 Proposed criteria for classifying a thoracic EHE as intermediate grade/high risk include increased mitotic rate (>1/mm2), necrosis, and moderate nuclear pleomorphism.10

Pleuropulmonary Blastoma

PPB is a very rare malignant primitive embryonal tumor of infancy and childhood.19,20 PPB should not be confused with the similarly named pulmonary blastoma, which is a subtype of sarcomatoid carcinoma (see Chapter 85), and has completely distinct clinical and pathologic characteristics. Despite the name, the earliest phase of PPB is thought to arise in the lung parenchyma and subsequently grow toward the pleural surfaces. For this reason, PPBs are considered primary tumors of the lung parenchyma.

Incidence and Clinical Features

The vast majority of PPBs occur in children under 5 years, although older children can rarely be affected and rare cases have been observed even into young adulthood.20,21 PPBs should be subtyped based on gross and microscopic proportions of cystic and solid components, as types 1 to 3: type 1 is entirely cystic, type 2 is solid and cystic, while type 3 is entirely solid.22 The average age seems to correlate with the subtype of PPB, with type 1 patients presenting at the youngest age (average 8 months) and type 3 patients presenting at an older average age (average 41 months).20,21 Infants with type 1 and 2 lesions often present in respiratory distress, and pneumothorax is also common at presentation due to the cystic nature of the mass.21 Children with type 2 and 3 PPB may present with localizing symptoms including cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.23 Imaging studies reveal a lung mass or consolidation, which may have a multiloculated cystic component.21 Most tumors are confined to the lung but may rarely extend to involve the mediastinum or chest wall, and some will be multifocal.24

Gross Pathology

The cystic component of PPB (if present) is characterized by large thin-walled multiloculated cysts that may collapse upon sectioning.20,25 The solid components may form nodules, plaques, or polypoid projections in an otherwise cystic lesion.20 The solid component may vary in appearance from firm and rubbery to soft and gelatinous.20 In cystic lesions, the specimen should be closely examined for any solid areas, which should be liberally sampled. Some lesions may appear relatively circumscribed, while others infiltrate the surrounding parenchyma.20

Microscopic Findings

The cystic spaces of PPB are lined by flattened to cuboidal metaplastic (nonneoplastic) respiratory epithelium, which is often attenuated and may be ciliated.20,21 Within the septa of the cysts, careful examination typically reveals primitive mesenchymal cells, which show small round blue cell or rhabdomyoblastic morphology.26 These cells often form a cambium layer below the metaplastic epithelium (Fig. 93.6), but they may be quite subtle and rare in some cases, so any case showing the characteristic large cysts lined by metaplastic epithelium should be carefully examined and liberally sampled. The solid component of PPB is frankly sarcomatous and has a diverse morphology. Observed patterns may be mixed, and often include small round blue cells/blastema, rhabdomyoblastic cells resembling embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, and/or high-grade spindle cell sarcoma.20,21 Embryonal (immature) or malignant-appearing cartilage is present in about half of PPBs and is a very helpful morphologic feature to suggest the diagnosis when identified.20 The proportion of observed cystic and solid components should be used to subtype PPBs. Type 1 PPBs are entirely cystic but still have identifiable primitive cells, type 2 is cystic and solid, and type 3 is completely solid.20,21 It seems that the immature cells of PPBs may regress completely (PPB-R), leaving only the cystic spaces lined by attenuated epithelium with fibrous septa, without any identifiable primitive cells.21 Tumors with the typical architecture but with no identifiable residual primitive cells should be categorized as PPB-R.21

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree