Figure 22.1

Congenital pulmonary adenomatous malformation

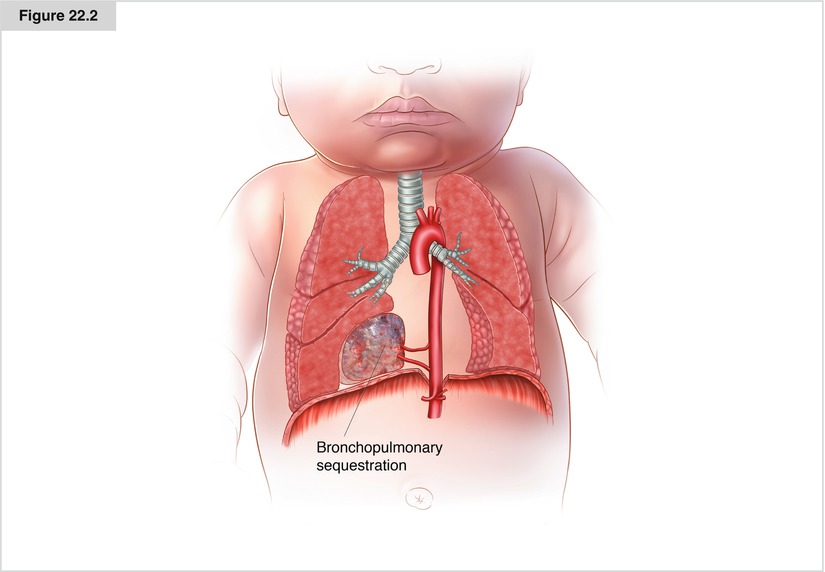

Figure 22.2

Bronchopulmonary sequestration

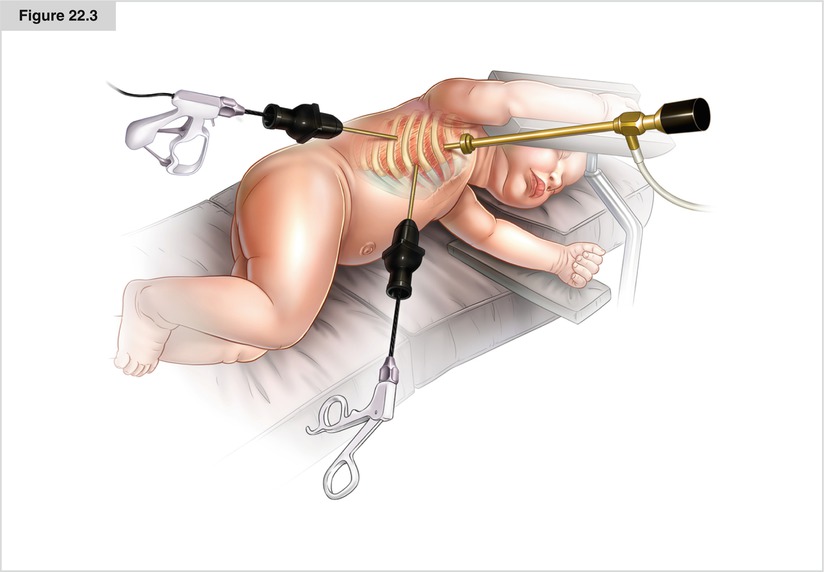

Figure 22.3

Thoracoscopy in infants

History

The first description in the English language literature of CPAM—also called CCAM (congenital cystic adenomatous malformation)—was written by Ch’in and Tang in 1949.

Since 1977, the histopathologic classification penned by JT Stocker has been widely quoted, although, by itself, it does not affect treatment decisions, has no prognostic value, and is not even sufficient to provide an accurate diagnosis.

Pulmonary sequestrations were first described in 1861 by the Austrian anatomist Rokitansky as accessory pulmonary lobes, but were renamed pulmonary sequestrations by Pryce in 1946. The first parenchymal lung lesion to be detected antenatally was reported in 1975 in Australia. Subsequently, large series reporting early outcomes were published in the 1990s.

Indications

There is no doubt that surgical intervention is necessary for postnatally symptomatic cystic or parenchymal pulmonary lesions; however, in the unborn fetus, a range of therapeutic options is available. Ultrasonically defined macrocystic disease may be aspirated or shunted using a thoracoamniotic shunt, or even excised with fetal surgery or intranatal techniques, such as the EXIT (ex utero intrapartum treatment) maneuver. Early thoracotomy to excise expanding cystic lesions is safe, is nearly free of complications, and allows appropriate growth of the normal compressed lung.

Most macrocystic lesions, stable lesions, and lesions with a fetal mediastinal shift come to surgery. Sometimes, prenatally observed cystic lesions become smaller, and this spontaneous shrinkage is prognostically favorable. However, true resolution of antenatally diagnosed lesions is the exception; therefore, they must be evaluated by frequent CT or MRI scans postnatally.

In 2009, Stanton et al. performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 41 reports describing 1,070 patients. They found that 505 neonates survived into infancy without surgery and only 16 of them (3.2 %) became symptomatic. The authors showed that for all ages, elective surgery was associated with significantly fewer complications than emergency surgery. The onset of symptoms occurred within the first 7 months of life. Therefore, resection must be planned before 10 months of age; most authors advise elective resection at the age of 6 months. Because lung tissue develops in the first year of life, this period of maturation should be utilized for the expected compensatory capacity of the rest of the lung tissue after resection.

When considering surgical intervention, one must weigh the risk of postoperative complications against the lifelong risk of leaving lesions in situ. There are many cases describing a correlation between CPAM and malignancy (rhabdomyosarcoma, adenocarcinoma, and bronchoalveolar carcinoma); however, there were no reports of malignancy in the series collected by Stanton et al.

So far, there is no identifiable prognostic feature in postnatal life suggesting the need for intervention, although there have been attempts to correlate size with outcome at the antenatal stage. Furthermore, there is no consensus regarding the indications for resecting small symptom-free lesions. Davenport et al. summarized: We continue to advocate excision of all “significant” lesions, even if asymptomatic, although this can be difficult to define. . .we believe that the accumulated hazards of pulmonary infection and a risk of malignancy later in life outweigh the risks of early, elective excisional surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree