Pulmonary Hypertension

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

• Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is defined by a mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) >25 mm Hg.1

• Discrimination of the type of PH (i.e., precapillary vs. postcapillary) requires additional information about the left heart’s filling pressures and the pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR).

Classification

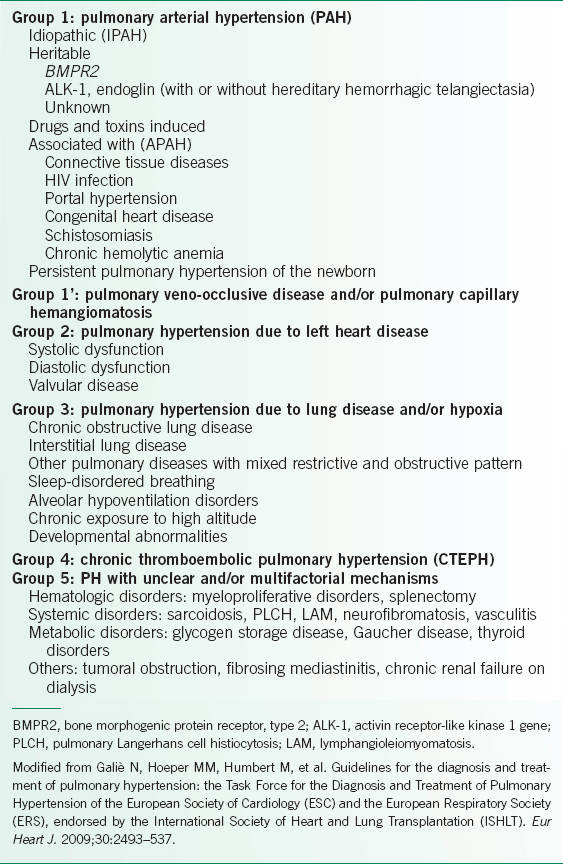

• PH is classified into five groups (Table 22-1).2,3

• Individuals can have more than one underlying condition leading to a so-called mixed form of PH.

• Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH, group 1) patients are stratified by World Health Organization (WHO) functional classes I–IV that guide therapies and provide a tool to monitor clinical response (Table 22-2).4

Epidemiology

• The most common type of PH in the developed world is group 2, followed by group 3.

• Group 3 PH tends to correlate with degree of severity of underlying lung disease and/or hypoxemia but exceptions include concomitant conditions having an additive effect, and a discordant degree of PH with the underlying lung disease as measured by spirometry (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea [OSA] and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]).

• Prevalence of PAH is estimated to be 15–25 cases per million with female/male ratio between 2:1 and 3:1. Prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) is estimated at 6 per million.1

• Survival rates for PAH at 1, 3, and 5 years are 84%, 67%, and 58%, respectively with a median survival of 3.6 years.5 However, survival can be substantially affected by etiology.

• Estimated cumulative incidence of PH after acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is 1.0% at 6 months, 3.1% at 1 year, and 3.8% at 2 years with cumulative burden of emboli being a risk factor.6

Pathophysiology

• The common finding in all forms of PH is elevated pressures within precapillary pulmonary vessels as blood flows across the pulmonary circuit.

• Group 1 PH (PAH) involves complex mechanisms that progressively narrow and stiffen the pulmonary arterioles.

Pathogenesis in PAH may vary with the different etiologies but converges upon endothelial and smooth muscle cell proliferation and dysfunction that result in the complex interplay of the following factors:

Pathogenesis in PAH may vary with the different etiologies but converges upon endothelial and smooth muscle cell proliferation and dysfunction that result in the complex interplay of the following factors:

Vasoconstriction caused by overproduction of vasoconstrictor compounds such as endothelin and insufficient production of vasodilators such as prostacyclin and nitric oxide.

Vasoconstriction caused by overproduction of vasoconstrictor compounds such as endothelin and insufficient production of vasodilators such as prostacyclin and nitric oxide.

Endothelial and smooth muscle proliferation due to mitogenic properties of endothelin and thromboxane A2 in the setting of low levels of inhibitory molecules, such as prostacyclin and nitric oxide.

Endothelial and smooth muscle proliferation due to mitogenic properties of endothelin and thromboxane A2 in the setting of low levels of inhibitory molecules, such as prostacyclin and nitric oxide.

In situ thrombosis of small- and medium-sized pulmonary arteries resulting from platelet activation and aggregation.

In situ thrombosis of small- and medium-sized pulmonary arteries resulting from platelet activation and aggregation.

The physiologic consequences of this proliferative vasculopathy are an increase in PVR and right ventricle (RV) afterload.

The physiologic consequences of this proliferative vasculopathy are an increase in PVR and right ventricle (RV) afterload.

Complex origins of PAH include infectious/environmental insults in the setting of predisposing comorbidities and/or underlying genetic predisposition, for example, gene mutation of bone morphogenetic protein receptor II (BMPR II) or activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1).1,7,8

Complex origins of PAH include infectious/environmental insults in the setting of predisposing comorbidities and/or underlying genetic predisposition, for example, gene mutation of bone morphogenetic protein receptor II (BMPR II) or activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1).1,7,8

BMPR2 gene mutations are found in 75% of familial PAH and 25% of IPAH, while ALK1 gene mutations, causative of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, rarely present with PAH.1,9

BMPR2 gene mutations are found in 75% of familial PAH and 25% of IPAH, while ALK1 gene mutations, causative of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, rarely present with PAH.1,9

• Elevated pressures in groups 2–5 result from:

Elevated downstream pressures on the left side of the heart (group 2),

Elevated downstream pressures on the left side of the heart (group 2),

Hypoxemic vasoconstriction (group 3),

Hypoxemic vasoconstriction (group 3),

Occlusion of the vasculature by material foreign to the lung (group 4),

Occlusion of the vasculature by material foreign to the lung (group 4),

High flow that exceeds capacitance of the pulmonary circuit (group 5), or

High flow that exceeds capacitance of the pulmonary circuit (group 5), or

Blood vessel narrowing and destruction from processes external to the vasculature (group 3, group 5).

Blood vessel narrowing and destruction from processes external to the vasculature (group 3, group 5).

TABLE 22-1 2008 DANA POINT CLINICAL CLASSIFICATION OF PULMONARY HYPERTENSION (PH)

TABLE 22-2 WHO FUNCTIONAL CLASSIFICATION

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

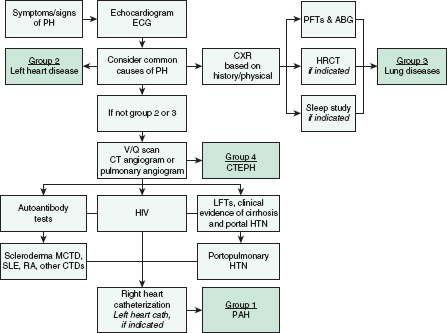

An algorithm for evaluating PH is outlined in Figure 22-1.

History

• Dyspnea with exertion is the most often reported symptom for patients with PH. Orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea are important clues of left heart disease and group 2 PH. Symptoms that reflect more advanced disease and secondary RV dysfunction include fatigue, syncope, peripheral edema, and angina.

• Hoarseness can also be encountered because of left recurrent laryngeal nerve compression by the enlarging pulmonary artery (i.e., Ortner syndrome).

• Past medical history relevant to several organ systems, including the respiratory, cardiovascular, hepatic, rheumatologic, and hematologic systems must be explored.

• Particular emphasis should be placed on prior cardiac conditions, including myocardial infarction, heart failure (HF), arrhythmias, rheumatic heart disease, other valvular heart disease, and congenital heart disease.

• Social history should focus on prior or current tobacco and alcohol use, as well as illicit or recreational drug use, particularly methamphetamines or cocaine.

• Family history should also be explored to exclude a genetic predisposition.

• Risk factors for exposure to HIV may disclose an unexpected etiology for PH.

• Careful medication history to document use of current or past drugs linked to development of PH is also necessary. This includes anorexigens (e.g., fenfluramine, dexfenfluramine, diethylpropion) and chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., mitomycin).1

FIGURE 22-1. Diagnostic approach to pulmonary arterial hypertension. PH, pulmonary hypertension; PFT, pulmonary function tests; ABG, arterial blood gases; HRCT, high-resolution CT; V/Q scan, ventilation/perfusion scan; CTEPH, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; LFT, liver function test; HTN, hypertension; MCTD, mixed connective tissue disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CTD, connective tissue disease; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Physical Examination

• A thorough physical examination to corroborate or refute suspicions of underlying medical problems should be performed; attention should be directed toward the cardiopulmonary examination.

• Auscultatory examination of the heart may reveal an accentuated S2 sound with a prominent P2 component, systolic ejection murmur at left lower sternal border due to tricuspid regurgitation, and diastolic decrescendo murmur (Graham Steell murmur) along the left sternal border due to pulmonary insufficiency. Additional cardiac finding, including continuous murmurs or rumbles and fixed-split S2, may suggest an underlying congenital cardiac defect.

• As PH worsens and right HF ensues, resting tachycardia, S3 gallop, elevated jugular venous pulsation of the neck, hepatomegaly, ascites, peripheral edema, diminished peripheral pulses, and cyanosis occur. Presence of these findings, in the absence of clues of left heart disease, should raise suspicion for right HF due to PH.

• Digital clubbing indicates underlying conditions such as interstitial lung disease (ILD), bronchiectasis, or congenital heart disease.

Diagnostic Criteria

• PH is defined as mean PAP >25 mm Hg.1

PAH requires normal left ventricular (LV) filling pressures (i.e., pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), left atrial pressure, or left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) ≤15 mm Hg).

PAH requires normal left ventricular (LV) filling pressures (i.e., pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), left atrial pressure, or left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) ≤15 mm Hg).

Some centers also require an elevated PVR (≥3 Wood units) to establish PAH.

Some centers also require an elevated PVR (≥3 Wood units) to establish PAH.

• Diagnosis of PAH requires a right heart catheterization (RHC).

• Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) can be estimated noninvasively by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), whereby a PASP >40 mm Hg is considered abnormal and suggestive of PH but is not diagnostic.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

• Essential laboratory studies to evaluate unexplained PH mirror the studies of a general medical evaluation: complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and coagulation studies may offer diagnostic clues and direct further exploration. A prerenal pattern of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine elevations in conjunction with passive congestion of the liver is a sign of advanced right HF and low cardiac output.

• Screening for collagen vascular disease with antinuclear antibody (ANA), anticentromere antibody, rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-scl-70 antibody, and antiribonucleoprotein antibody should be completed, as the associated underlying conditions are linked to PAH.

• Thyroid studies, hemoglobin electrophoresis for sickle cell disease, HIV serology, hepatitis serologies, antiphospholipid antibody, or anticardiolipin antibody should also be performed if clinical suspicions exist.

• Arterial blood gas can provide invaluable information. Significant resting hypoxemia should raise suspicion for right-to-left shunt, severely reduced cardiac output, or underlying pulmonary disease. Significant hypercarbia supports a group 3 diagnosis.

Electrocardiography

• RV enlargement is suspected by the presence of an R wave in V1 or an S wave in lead V6 while RV strain appears as a triad of S wave in lead I, Q wave in lead III, and inverted T wave in lead III. Other potential findings in cases of PH include right atrial enlargement and right bundle branch block.

• LV hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, left axis deviation, atrial fibrillation, or evidence of prior myocardial infarction provide clues of significant left heart disease that could lead to group 2 PH.

Imaging

• CXR

Features indicative of PH are enlarged central pulmonary arteries on frontal views and RV enlargement on lateral examination. When PAPs reach systemic levels, pulmonary artery calcifications can be seen.

Features indicative of PH are enlarged central pulmonary arteries on frontal views and RV enlargement on lateral examination. When PAPs reach systemic levels, pulmonary artery calcifications can be seen.

Obliteration of the distal pulmonary arteries leads to tapering of vessels in the peripheral third of the lung parenchyma, referred to as pruning, is classically seen in IPAH.

Obliteration of the distal pulmonary arteries leads to tapering of vessels in the peripheral third of the lung parenchyma, referred to as pruning, is classically seen in IPAH.

In contrast, prominent pulmonary arteries extending to the periphery of the lung suggest systemic-to-pulmonary shunts and a hypercirculatory state (e.g., atrial or ventricular septal defects).

In contrast, prominent pulmonary arteries extending to the periphery of the lung suggest systemic-to-pulmonary shunts and a hypercirculatory state (e.g., atrial or ventricular septal defects).

CXR should also be reviewed for underlying cardiopulmonary diseases, including ILD, emphysema, or HF.

CXR should also be reviewed for underlying cardiopulmonary diseases, including ILD, emphysema, or HF.

• Ventilation/perfusion scan

Provides an easy and sensitive screen for the detection of chronic thromboembolic disease.

Provides an easy and sensitive screen for the detection of chronic thromboembolic disease.

While PH due to nonembolic processes, such as IPAH, can display a heterogeneous or mottled perfusion pattern, anatomic perfusion defects of the segmental or lobar level are more concerning for thromboembolic disease.

While PH due to nonembolic processes, such as IPAH, can display a heterogeneous or mottled perfusion pattern, anatomic perfusion defects of the segmental or lobar level are more concerning for thromboembolic disease.

Differential diagnosis for an abnormal perfusion scan also includes pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (widespread obstruction of the pulmonary veins due to fibrous tissue), mediastinal fibrosis, or pulmonary vasculitis.

Differential diagnosis for an abnormal perfusion scan also includes pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (widespread obstruction of the pulmonary veins due to fibrous tissue), mediastinal fibrosis, or pulmonary vasculitis.

• Chest CT

While CT angiography can display features of chronic thromboembolic disease, it is less sensitive and less predictive of surgical response than the ventilation/perfusion scan.

While CT angiography can display features of chronic thromboembolic disease, it is less sensitive and less predictive of surgical response than the ventilation/perfusion scan.

Chest CT may be necessary to exclude mediastinal disease, (e.g., mediastinal fibrosis or compressive lymphadenopathy).

Chest CT may be necessary to exclude mediastinal disease, (e.g., mediastinal fibrosis or compressive lymphadenopathy).

High-resolution chest CT (HRCT) can exclude ILD, if suspicion exists.

High-resolution chest CT (HRCT) can exclude ILD, if suspicion exists.

• TTE

TTE with Doppler and agitated saline injection serves as an initial test to identify PH.

TTE with Doppler and agitated saline injection serves as an initial test to identify PH.

If tricuspid regurgitation is present, Doppler interrogation allows for estimation of PASP.

If tricuspid regurgitation is present, Doppler interrogation allows for estimation of PASP.

TTE also identifies potential left-sided cardiac causes of PH and provides estimate of LV systolic and diastolic function.

TTE also identifies potential left-sided cardiac causes of PH and provides estimate of LV systolic and diastolic function.

The agitated saline, so-called bubble study may discover an intracardiac shunt; a patent foramen ovale allows for right-to-left shunting that could explain exertional hypoxemia in PH patients, but is not considered causative of PH.

The agitated saline, so-called bubble study may discover an intracardiac shunt; a patent foramen ovale allows for right-to-left shunting that could explain exertional hypoxemia in PH patients, but is not considered causative of PH.

Finally, presence of a pericardial effusion is a predictor of mortality in PAH.1

Finally, presence of a pericardial effusion is a predictor of mortality in PAH.1

Diagnostic Procedures

• Pulmonary function testing (PFT)

PFTs should be inspected for obstructive lung disease while measurement of lung volumes may provide a clue for ILD.

PFTs should be inspected for obstructive lung disease while measurement of lung volumes may provide a clue for ILD.

DLCO values, if normal or elevated, argue against PH.

DLCO values, if normal or elevated, argue against PH.

Classically, patients with IPAH exhibit normal spirometry, minimally reduced total lung capacity (∼75%), significant reduction of DLCO, normal resting PaO2, and exercise-induced hypoxemia.

Classically, patients with IPAH exhibit normal spirometry, minimally reduced total lung capacity (∼75%), significant reduction of DLCO, normal resting PaO2, and exercise-induced hypoxemia.

• RHC1

RHC is the gold standard for diagnosing PAH.

RHC is the gold standard for diagnosing PAH.

Pressure measurements include PA pressures, RV end-diastolic pressure, right atrial pressure, and the PCWP; in particular, the right atrial pressure is an important predictor of survival.

Pressure measurements include PA pressures, RV end-diastolic pressure, right atrial pressure, and the PCWP; in particular, the right atrial pressure is an important predictor of survival.

Cardiac output is determined by either the thermodilution or Fick method. Either can be used but both have drawbacks. Thermodilution is affected by significant tricuspid regurgitation. For Fick, direct oxygen consumption (VO2) is rarely measured and only an assumed Fick calculation is typically done.

Cardiac output is determined by either the thermodilution or Fick method. Either can be used but both have drawbacks. Thermodilution is affected by significant tricuspid regurgitation. For Fick, direct oxygen consumption (VO2) is rarely measured and only an assumed Fick calculation is typically done.

Once the other aforementioned measures are made, PVR can be calculated as (mean PAP – PCWP)/cardiac output, or the ratio of pressure decline across the pulmonary circuit and the cardiac output.

Once the other aforementioned measures are made, PVR can be calculated as (mean PAP – PCWP)/cardiac output, or the ratio of pressure decline across the pulmonary circuit and the cardiac output.

An acute vasodilator challenge can also be performed to guide the choice of therapeutic agent in group 1 (PAH) patients. A short-acting vasodilator such as inhaled nitric oxide, IV adenosine, or IV epoprostenol is administered. A 10 mm Hg drop in the mean PAP and a concluding mean PAP <40 mm Hg without systemic hypotension or a decrease in cardiac output signifies a significant acute hemodynamic response.

An acute vasodilator challenge can also be performed to guide the choice of therapeutic agent in group 1 (PAH) patients. A short-acting vasodilator such as inhaled nitric oxide, IV adenosine, or IV epoprostenol is administered. A 10 mm Hg drop in the mean PAP and a concluding mean PAP <40 mm Hg without systemic hypotension or a decrease in cardiac output signifies a significant acute hemodynamic response.

• Left heart catheterization (LHC) should be performed to rule out coronary artery disease and/or directly measure the LVEDP when left heart disease is strongly suspected or the PCWP is felt to be unreliable.

• Polysomnography should be obtained if there is a concern for OSA or obesity hypoventilation syndrome as a contributing component to PH.

TREATMENT

• Management of PH depends on the specific category determined after a comprehensive evaluation.

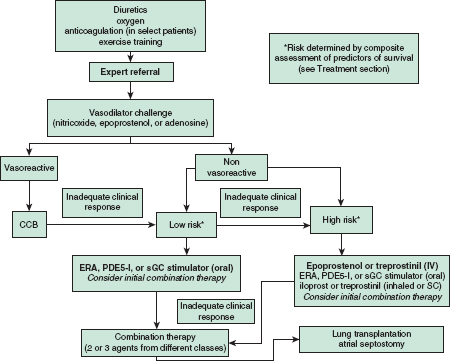

• A treatment algorithm for PAH (i.e., group 1) is presented in Figure 22-2.1

Treatment of Groups 2–4

• Group 2

PH owing to left heart disease (group 2) should receive appropriate therapy for underlying causative left heart conditions with a hemodynamic goal of lowering the PCWP (and LVEDP) as much as possible.

PH owing to left heart disease (group 2) should receive appropriate therapy for underlying causative left heart conditions with a hemodynamic goal of lowering the PCWP (and LVEDP) as much as possible.

Patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction often develop secondary PH and exertional dyspnea and require afterload-reducing agents (to minimize LV afterload), diuretics (to avoid excess volume), and negative chronotropes (to avoid tachycardic states).

Patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction often develop secondary PH and exertional dyspnea and require afterload-reducing agents (to minimize LV afterload), diuretics (to avoid excess volume), and negative chronotropes (to avoid tachycardic states).

Chronic use of NSAIDs can aggravate HF and should be avoided.

Chronic use of NSAIDs can aggravate HF and should be avoided.

Subset of patients of LV systolic HF and associated PH appear to benefit from sildenafil (a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, PDE-5I), in terms of exertional capacity, hemodynamics during exercise, and quality of life.10,11 Sildenafil should only be used if PH is persistent after optimization of LV filling pressures (i.e., near-normal PCWP or LVEDP) and optimization of LV systolic function. Careful hemodynamic assessment should be used to demonstrate an elevated PVR.

Subset of patients of LV systolic HF and associated PH appear to benefit from sildenafil (a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, PDE-5I), in terms of exertional capacity, hemodynamics during exercise, and quality of life.10,11 Sildenafil should only be used if PH is persistent after optimization of LV filling pressures (i.e., near-normal PCWP or LVEDP) and optimization of LV systolic function. Careful hemodynamic assessment should be used to demonstrate an elevated PVR.

• Group 3

PH caused by parenchymal lung diseases (group 3) should be treated with appropriate therapies for the underlying pulmonary condition: bronchodilators, pulmonary rehabilitation (obstructive lung disease), immunomodulators (ILDs), and noninvasive ventilation (OSA and/or hypoventilation syndrome).

PH caused by parenchymal lung diseases (group 3) should be treated with appropriate therapies for the underlying pulmonary condition: bronchodilators, pulmonary rehabilitation (obstructive lung disease), immunomodulators (ILDs), and noninvasive ventilation (OSA and/or hypoventilation syndrome).

Adequate oxygen saturation (SpO2 ≥90%) is critical to avoid hypoxic vasoconstriction and cor pulmonale.

Adequate oxygen saturation (SpO2 ≥90%) is critical to avoid hypoxic vasoconstriction and cor pulmonale.

• Group 4

Group 4 PH (CTEPH) can be cured by pulmonary thromboendarterectomy at specialized centers and requires careful screening to determine candidacy and expected hemodynamic response.1,12

Group 4 PH (CTEPH) can be cured by pulmonary thromboendarterectomy at specialized centers and requires careful screening to determine candidacy and expected hemodynamic response.1,12

When the disease is considered nonsurgical due to distal predominance of the culprit lesions, medical therapy (as in PAH) can be attempted.

When the disease is considered nonsurgical due to distal predominance of the culprit lesions, medical therapy (as in PAH) can be attempted.

Regardless, lifelong therapeutic anticoagulation with warfarin should be prescribed with a goal INR of 2.0–3.0.1

Regardless, lifelong therapeutic anticoagulation with warfarin should be prescribed with a goal INR of 2.0–3.0.1

FIGURE 22-2. Pulmonary arterial hypertension treatment algorithm. Only patients with an acute vasodilator response (see text) should receive CCB treatment. Typical first-line treatment is listed first. Risk determined by variables listed in text. CCB, calcium channel blocker; ERA, endothelin receptor antagonist; PDE-5I, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor; sGC, soluble guanylate cyclase. (Modified from McLaughlin V, Archer S, Badesch D, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1573–619.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree