Pulmonary Adenomas

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Sclerosing Pneumocytoma (Hemangioma)

Sclerosing pneumocytoma is a distinctive benign tumor of pneumocyte origin. Although the epithelial nature of the tumor has been established for over 25 years,1 the term “sclerosing hemangioma” is entrenched in the medical literature and appears synonymously with “pneumocytoma” to this day.

Sclerosing pneumocytomas are rare, with few published series of more than 10 patients2,3; there appears to be a higher prevalence in China than in Western countries.4,5,6,7 There is a >5:1 female predominance, up to 15:1 in China.6 The mean or median age was 46 in the two largest series published.3,4 Most are discovered incidentally, although some patients present with cough or hemoptysis.

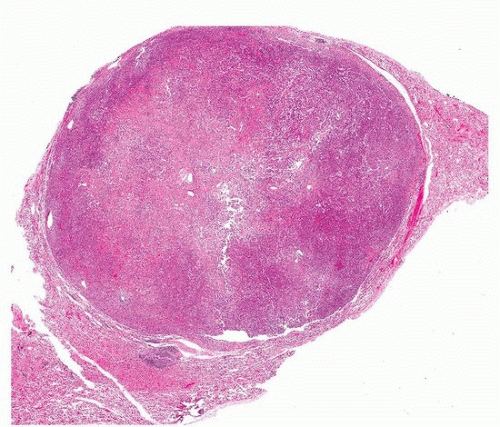

Although a predilection for the right middle lobe has been reported,4 there was no site predilection in the largest study from the United States.3 Fewer than 5% of sclerosing pneumocytomas are multiple, and when they are, the nodules are usually in the same lobe, as a dominant mass with satellite nodules.3,5 The typical tumor is peripheral or subpleural. Rare endobronchial8 or visceral pleural-based tumors have been reported.3 Sclerosing pneumocytomas are typically well circumscribed, solid, and homogeneous, without cystic areas (only 3% in the largest series).3 Foci of hemorrhage are seen in about one-fourth of tumors and

correspond to the hemorrhagic histologic pattern. The mean size is 25 to 30 mm, with the largest reported at 8 cm.6 By computed tomographic scans, most are round, with absent or small spicules and homogenous. There may be calcifications or heterogeneous enhancement, especially in larger tumors. Because of the nonspecificity of computed tomographic findings and positivity on positron emission tomography, many sclerosing pneumocytomas are diagnosed as probably malignancies.5,7,9

correspond to the hemorrhagic histologic pattern. The mean size is 25 to 30 mm, with the largest reported at 8 cm.6 By computed tomographic scans, most are round, with absent or small spicules and homogenous. There may be calcifications or heterogeneous enhancement, especially in larger tumors. Because of the nonspecificity of computed tomographic findings and positivity on positron emission tomography, many sclerosing pneumocytomas are diagnosed as probably malignancies.5,7,9

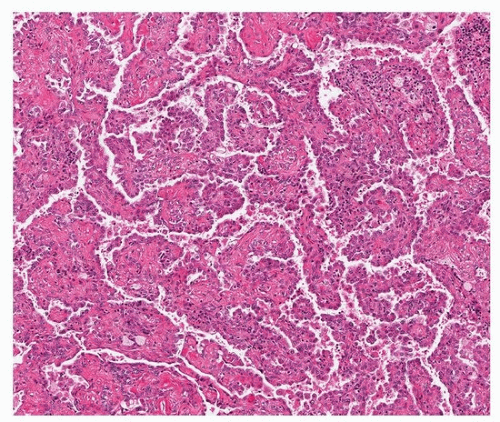

FIGURE 67.1 ▲ Sclerosing pneumocytoma. At low power, the tumor is highly circumscribed. At this magnification, a benign tumor or metastatic lesion is likely. |

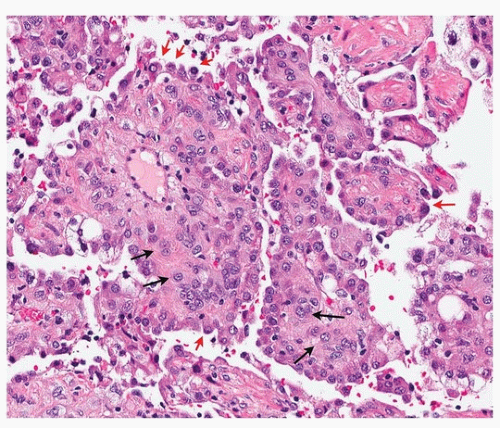

Histologically, there are two cell types (round and surface) that classically form four overlapping patterns. The most common is the papillary pattern (Figs. 67.1, 67.2, 67.3), followed by sclerotic, solid, and hemorrhagic patterns (Figs. 67.4 and 67.5). About one-half of tumors show all four. It is generally believed that the “tumor” cell is the round cell, which is present within the papillary stalks and in the sclerotic and solid areas, and that the cells lining the surfaces of the papillae and tubular structures are reactive (“activated”) pneumocytes. The hemorrhagic pattern is characterized by blood-filled spaces lined by pneumocytes and the sclerotic pattern by small nests of round cells in a dense collagen stroma. The surface cells may show multinucleation and intranuclear inclusions. Entrapped cysts may be lined by reactive pneumocytes or ciliated bronchiolar epithelium that may fill with mucus.3

Immunohistochemically and ultrastructurally, the two cell types show divergent characteristics, the surface cells showing features of mature “type II” pneumocytes and the round cells more primitive pneumocytes (sometimes called “pneumoblasts”10). The finding of a low proliferative index in the round cells, compared to zero Ki-67 proliferative index in the surface cells, supports this concept,6 as well as the finding of hepatocyte nuclear factor-3α and nuclear factor-3β within the round cells.10

For diagnostic purposes, immunohistochemistry is useful in separating the round cells from the more differentiated, reactive surface cells (Figs. 67.6, 67.7, 67.8, 67.9; Table 67.1). Round cells are negative for

cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and usually negative (about 80%) for cytokeratin 7 and napsin A. Both populations express TTF-1 and EMA.3,11,12 Endocrine differentiation with synaptophysin may occur in some tumors, and vimentin is more likely positive in the tumor cells than in the surface cells.3 In practice, the tumor and reactive cell populations often seem to overlap, but it is generally not difficult to identify that there are two separate cell types.

cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and usually negative (about 80%) for cytokeratin 7 and napsin A. Both populations express TTF-1 and EMA.3,11,12 Endocrine differentiation with synaptophysin may occur in some tumors, and vimentin is more likely positive in the tumor cells than in the surface cells.3 In practice, the tumor and reactive cell populations often seem to overlap, but it is generally not difficult to identify that there are two separate cell types.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree