11

Protozoal and Helminthic

Pulmonary Disease

Protozoal Infection

Amoebiasis

Pulmonary infection by amoeba is most often caused by Entamoeba histolytica, a species usually associated with dysentery.1 Rare cases of pneumonia caused by species of the Hartmanella-Acanthamoeba group also have been reported.2 Pathogenic organisms occur as both cysts and trophozoites; the latter are the tissue-based form and often have ingested red blood cells within their cytoplasm.

Amoebic dysentery is seen throughout the world in environments where hygiene is poor. Cysts are passed in the feces of affected individuals (most of whom are asymptomatic) and are ingested in contaminated water or food. They are acid resistant and travel through the stomach to the small intestine, where the trophozoites excyst, pass to the colon, and cause epithelial ulceration. Organisms enter the colonic veins and pass to the liver, where micro- and macroabscesses may develop. Pulmonary disease is almost always secondary to hepatic involvement and can occur by several mechanisms. The most common is direct extension of a hepatic abscess across the diaphragm into the pleural space (causing empyema) or basal lung parenchyma (causing a pulmonary abscess or bronchobiliary fistula).3 Rarely, pulmonary disease develops at a distance from the liver by rupture of a hepatic abscess into a hepatic vein (resulting in pulmonary emboli of infected debris) or by lymphatic spread.1 Equally rarely, pulmonary disease occurs without hepatic involvement, in which case organisms probably reach the lungs or pleura via the hemorrhoidal veins (in association with lower rectal disease) or the thoracic duct.4

Affected lung shows poorly defined areas of necrosis that characteristically have a mucinous, hemorrhagic appearance that has been likened to anchovy paste or chocolate sauce.4 Histologically, there is a combination of necrosis, fibrosis, and nonspecific chronic inflammation. Although the term abscess is frequently applied to these lesions, polymorphonuclear leukocytes are uncommon. Trophozoites may be seen in tissue stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) at the junction of necrotic and normal lung. They may also be detected in sputum, pleural fluid, or material obtained by needle aspiration; however, they are often few in number, and both over-and underdiagnosis are said to be common.1

Pulmonary symptoms include cough, chest pain and hemoptysis. The cough is initially dry but may become productive of “chocolate sauce” material and, occasionally, bile. Evidence of disease in the liver (including right upper quadrant pain or tenderness) is present in most individuals.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular parasite that appears in tissue sections as a crescent-shaped trophozoite measuring 6 to 7 μm by 2 to 4 μm. In acute infection, the trophozoites multiply rapidly (tachyzoites); in chronic infestation, they do so more slowly (bradyzoites). In the latter form of disease, intracellular cysts measuring 200 to 1011 μm in diameter and surrounded by a toxoplasma-produced membrane develop within the host cell cytoplasm. The organism can be identified with H&E and Giemsa stains; its nucleus stains red and cytoplasm blue with Romanowsky stain.

The disease occurs in many wild and domestic animals throughout the world, particularly in those of the cat family. Humans usually are infected by ingesting contaminated stool or partly cooked meat. Organisms also can be transmitted accidentally in the laboratory, in transfused blood, and in transplanted organs. Clinically significant infection in adults occurs most often in immunocompromised individuals, particularly those who have AIDS, organ transplants, or leukemia/lymphoma, or have received corticosteroid therapy;5–7 most such infections are believed to be the result of reactivation of latent organisms. Pneumonia is usually part of a systemic infection and is manifested clinically by nonproductive cough and dyspnea.

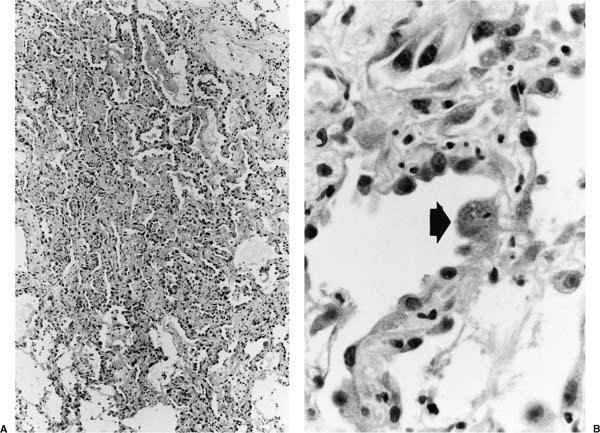

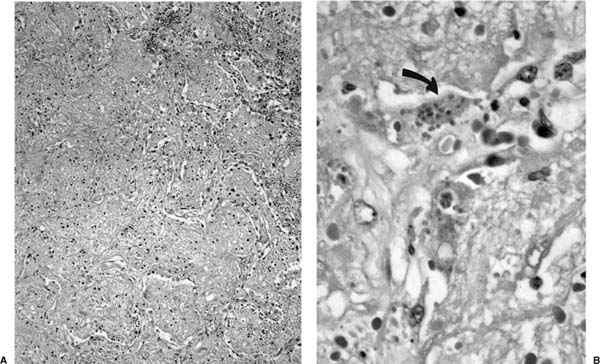

Early toxoplasmosis is manifested histologically as interstitial pneumonitis, sometimes associated with an airspace exudate (Fig. 11–1); a full-blown pattern of diffuse alveolar damage is seen in some cases.8 As disease progresses, parenchymal necrosis develops and may become extensive (Fig. 11–2). Nodular disease representing hematogenous spread is seen in some patients.9 Trophozoites may be seen in the cytoplasm of hyperplastic alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages, free in necrotic tissue, and in specimens of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (Figs. 11–1 and 11–2).10 Confirmation of the identity of the organism in these specimens is aided by immunohistochemical investigation.8

Miscellaneous Protozoal Infections

Clinically evident pulmonary disease is not uncommon in malaria, particularly in patients infested with Plasmodium falciparum.11 Clinical findings range from mild cough with evidence of airflow obstruction to fulminant respiratory failure and death, the latter usually being the result of acute respiratory distress syndrome.12,13 Histologic findings in the latter cases are those of diffuse alveolar damage. Organisms may be identified in red blood cells within pulmonary capillaries.14

Several species of Trichomonas, particularly T. tenax, can be found in the mouth and bronchial washings of patients who have poor oral hygiene.15 Their presence in pleural fluid and necrotic lung tissue, as well as the clinical response to drainage and metronidazole, suggests that they are the cause of empyema or pneumonia in some patients.15–17 It also has been hypothesized that Trichomonas organisms feed on the bacteria that are frequently identified in the focus of pleuropulmonary infection; Lewis et al16 stated that if this is the case, it is unclear to what extent the organisms are pathogenic or “saprophytic.” The organisms can be identified on Wright-Giemsa–and Papanicolaou-stained smears.18

FIGURE 11–1 Toxoplasmosis. (A) Low-magnification view shows interstitial pneumonitis and an airspace exudate. (B) Magnified view shows organisms within the cytoplasm of a cell on the alveolar surface (arrow). (From Fraser RS et al. Fraser and Paré’s Diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest, 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999.)

FIGURE 11–2 Toxoplasmosis. (A) Low-magnification view shows airspace filling with a proteinaceous exudate and focal necrosis. (B) Magnified view shows trophozoites within dead cells (arrow) and free in the extracellular exudate.

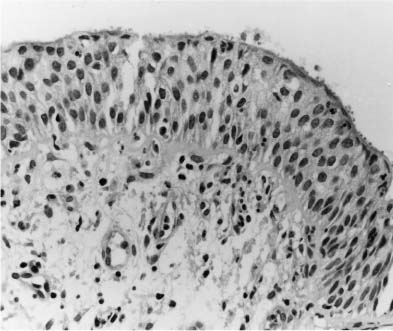

Cryptosporidia are well recognized as a cause of chronic diarrhea in patients who have AIDS. In this setting, they also have been identified in sputum and BAL fluid, on the surface of the airway (Fig. 11–3) or bronchial gland epithelium,19–21 and in association with a Rhodococcus pulmonary abscess.22 Some cases also have been reported of infection in individuals who have other immunosuppressive diseases.23 The organisms most likely gain access to the lungs by aspiration of contaminated material from the small intestine. The predominant clinical finding is cough.

Microsporidiosis caused by organisms of the genera Enterocytozoon and Encephalitozoon is most commonly manifested by intestinal or ocular disease in patients who have AIDS. Disseminated disease with involvement of the lungs has been reported in several patients.24–26 Histologic examination has shown tracheobronchitis and/or bronchiolitis; radiologic evidence of pneumonia also has been reported.27 Organisms have been identified in the supranuclear cytoplasm of airway epithelial cells obtained by biopsy26 and in macrophages in sputum or BAL fluid.24 Symptoms include cough and chest pain.

FIGURE 11–3 Cryptosporidiosis. Bronchial mucosa showing mild chronic inflammation and hyperplastic epithelium. Cryptosporidia are evident as small round dots on its surface.

Infection by Leishmania donovani (the cause of visceral leishmaniasis) rarely results in clinically significant pulmonary disease; however, interstitial pneumonitis associated with cells containing characteristic Leishman-Donovan bodies has been reported28 and organisms have been identified in macrophages obtained by BAL.29 Giardia lamblia has been suspected as the cause of pneumonitis in a patient with cancer from whom it was isolated from BAL fluid.30 Babesiosis is an acute illness caused by protozoa of the genus Babesia and characterized clinically by fever, myalgia, hemolytic anemia, hemoglobinuria, and jaundice. The acute respiratory distress syndrome is a rare complication.31,32

Helminthic Infection

Ascariasis

Most cases of human ascariasis are caused by Ascaris lumbricoides. The adult female worm lives in the small intestine, where it may produce as many as 250,011 eggs per day. When ingested by another host (usually via contaminated food or dirty hands), the ovum hatches in the small intestine. The resulting larvae pass via the intestinal vessels to the lungs, where they are trapped by the alveolar capillaries and emigrate into the airspaces. Here, they develop into third-stage larvae that migrate up the airways to the larynx, where they are swallowed to complete their odyssey by developing into mature worms in the small intestine.

Pulmonary disease is most often caused by migration of the third-stage larvae, and is manifested histologically by eosinophilic pneumonia or bronchitis.33 Larvae may be seen in the airspaces or airway lumen. Rarely, granulomas containing Ascaris ova have been identified within the lung parenchyma at autopsy, probably representing embolization from an extrapulmonary source.33 Adult Ascaris worms have been found within the bronchi in association with foci of bronchopneumonia; it has been assumed that they have been aspirated during vomiting and that the pneumonia is related to the aspiration rather than the organism itself.

Pulmonary symptoms consist of cough (usually non-productive), retrosternal chest pain, and in more severe cases, hemoptysis and dyspnea.

Strongyloidiasis

Most cases of strongyloidiasis are caused by Strongyloides stercoralis, a nematode that is prevalent in tropical and temperate areas throughout the world.34 S. fulleborni also infests individuals in Africa and produces disease similar to that caused by S. stercoralis. Infestation develops when free-living filariform larvae penetrate the skin and pass via the blood to the lung. They exit from the pulmonary capillaries into the alveoli and travel up the airways and down the esophagus to the small intestine, where they develop into adult females that take up residence and lay eggs in the mucosal crypts. As they pass through the gut, eggs develop into noninfectious rhabditiform larvae that are passed in the stool to the soil, where they develop into infectious filariform larvae. In some cases, rhabditiform larvae also transform directly into the filariform organisms within the gut, thus leading to autoinfection by direct penetration of the intestinal mucosa or perianal skin (“hyperinfection”).

The disease is endemic in tropical and subtropical areas where the climate is warm and the soil moist; depending on the particular geographic region, infestation has been estimated to affect about 10 to 50% of the population.35 In the majority of cases, infestation is accompanied by mild or no clinical symptoms; however, severe disease can occur, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, as a result of overwhelming infestation.36,37

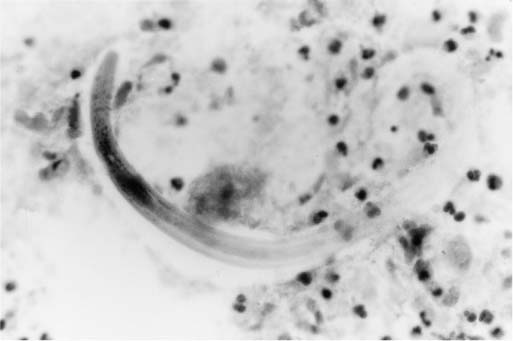

FIGURE 11–4 Strongyloides stercoralis. Bronchial wash specimen shows a curved larva of S. stercoralis in a background of neutrophils. (From Fraser RS et al. Fraser and Paré’s Diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest, 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999.)

Pulmonary disease is caused principally by migration of larvae through the alveolar capillaries into the adjacent airspaces. The associated reaction may consist only of edema and hemorrhage; however, an acute inflammatory exudate and, occasionally, granulomatous inflammation can be seen.38 A pattern of interlobular septal fibrosis also has been reported.39 Rarely, filiform larvae develop into adult worms within the lung itself.40 The organism can be identified on sections stained with H&E and in sputum stained by the Papanicolaou method (Fig. 11–4).41

Pulmonary symptoms are often mild or absent; hemoptysis and dyspnea occur occasionally. Signs and symptoms of asthma develop or worsen in some patients.42

Dirofilariasis

Pulmonary dirofilariasis is caused by most often by Dirofilaria immitis, an organism that is a natural parasite of dogs and, less commonly, cats and a variety of wild carnivores.43 Infestation by D. repens, an organism that usually affects the subcutaneous tissue, also has been reported to involve the lung occasionally.44 Rarely, pulmonary arteries within a focus of necrotic lung similar to that seen with D. immitis have been found to contain degenerated worms morphologically consistent with Wuchereria bancrofti or Brugia malayi.45,46

Infestation with D. immitis begins when microfilariae are regurgitated into the skin by infected mosquitoes. The parasites migrate from the subcutaneous tissue to the right heart chambers, where they mature into adult worms that release microfilaria into the blood. Several species of mosquito can act as intermediaries in dispersal of the organism to both definitive hosts and humans. Because humans are not a natural host, the organism does not complete its life cycle and dies before reaching sexual maturity; it is then carried into the pulmonary circulation where it lodges in a peripheral vessel and causes necrosis of lung tissue.

As might be expected, human dirofilariasis is seen in areas where there is a high canine infection rate. In North America, this is most pronounced along the eastern seaboard. Although only ~250 cases of human disease have been reported, there is serologic evidence that the condition may be more common than this figure suggests;47 in fact, some asymptomatic individuals appear to have had spontaneously resolving pulmonary nodules.47

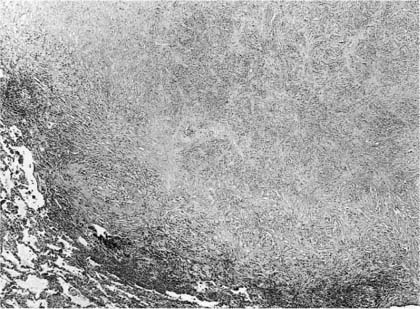

Pathologically, pulmonary disease is characterized by a solitary, more or less well-circumscribed, spherical or lobulated nodule, usually located in the subpleural parenchyma.43,48 Histologically, the nodule is composed predominantly of necrotic lung (Fig. 11–5); although this often has a coagulative appearance, caseous-like necrosis is seen in ~30% of cases.43 The necrotic tissue is surrounded by a variable amount of fibrous tissue and a chronic inflammatory cellular infiltrate, which may be granulomatous or nonspecific in type; eosinophils are prominent in some cases. One or more immature worms can be identified, most often within a pulmonary artery in the necrotic tissue. They usually measure 100 to 300 μm in cross section and have abundant somatic muscle and a prominent, multilayered cuticle that projects inward to form two longitudinal ridges (Fig. 11–6).

FIGURE 11–5 Dirofilariasis. A focus of necrotic lung parenchyma is surrounded by fibrous tissue and a chronic nonspecific inflammatory infiltrate. The appearance is similar to that of resolving tuberculosis. (Courtesy Dr. T. Colby.)

FIGURE 11–6 Dirofilaria immitis. Partly degenerated organism within a pulmonary artery, showing muscle (m) and cuticle with longitudinal ridges (R).

Most patients are asymptomatic, the lesion coming to attention because of a screening radiograph; however, cough, chest pain, and/or hemoptysis have been found in as many as 45% in some series.43,49 The typical radiologic manifestation is a solitary, well-circumscribed nodule 0.5 to 4 cm in diameter. Slight enlargement has been recorded over several years in some cases. The diagnosis has been made on specimens obtained by transthoracic needle aspiration/biopsy,50 but more commonly occurs after the nodule has been removed because of suspicion of pulmonary carcinoma. Apart from the hazards associated with such surgery, infestation is associated with minimal morbidity.

Echinococcosis

Echinococcosis (hydatid disease) is caused by four species of the tapeworm Echinococcus, by far the most common of which is E. granulosus. Infestation by E. multilocularis (alveolar hydatid disease) is less frequent but much more serious, and uncommonly affects the lung; similar disease is caused rarely by E. oligarthus and E. vogeli.51,52

Echinococcus Granulosus

Echinococcosis caused by E. granulosus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree