The familial prevalence of Brugada syndrome (BrS) in a consecutive series of patients was prospectively determined. BrS is genetically determined with autosomal dominant transmission. The familial prevalence of the BrS is unknown. A detailed pedigree of each family of patients with BrS was assembled and permission was obtained to invite relatives for electrocardiography and an ajmaline challenge. Sixty-two of 98 patients participated in the study and were included over a 6-year period. SCN5A genotyping was performed in 56 of these 62 patients (90%). Electrocardiograms (ECGs) of 488 relatives (mean age 38 ± 20 years, 45% men) were recorded and 270 of these relatives agreed to undergo an ajmaline challenge. Spontaneous type 1 BrS ECG was found in 4 of 488 relatives (0.8%). In the group of relatives in whom ajmaline challenge was performed (n = 270), the finding was positive in 79 subjects (29%). SCN5A genotyping identified 5 other affected relatives. As a result, the total number of affected relatives was 88. Standard 12-lead ECG was normal in 64 of the 88 affected relatives (73%). Mean percentage of affected relatives per family was 27 ± 32% (95% confidence interval 19 to 35). Familial forms of BrS were observed in 41 of the 62 families (66%) and no SCN5A mutations were found in sporadic forms. In conclusion, after active family screening affected relatives were found in almost 1/3 of subjects. BrS appeared to be a familial disease in 2/3 of subjects.

The prevalence of the familial form of Brugada syndrome (BrS) has not been thoroughly assessed. One study reported a 36% rate of familial forms of BrS. Patients are usually identified sporadically. The existence of effective therapies, in particular implantable cardioverters–defibrillators (ICDs) or quinidine, justifies family screening to allow the diagnosis in symptomatic relatives. It may also be important to identify asymptomatic carriers because the risk of arrhythmia is increased in situations such as fever, electrolyte imbalance, or absorption of a large range of drugs. In patients presenting with BrS on electrocardiogram (ECG), the discovery of other carriers in the family eliminates an acquired cause for the electrocardiographic abnormality. The yield of systematic family screening is not known and its clinical value has not been clearly demonstrated for asymptomatic patients because risk stratification is still controversial. The aim of this prospective study was to examine the familial prevalence of BrS in all unrelated patients with BrS followed in our center.

Methods

This study was conducted from 2001 to 2007 according to French guidelines for genetic research and was approved by the local ethics committee. A detailed pedigree of the families of each patient with BrS was assembled and permission was obtained from the proband to invite relatives to undergo screening. Subjects were given information about the risks of BrS and the availability of effective prophylactic or therapeutic strategies that might be indicated in some subjects. Written informed consent was obtained from each family member. Investigation included review of medical history, complete physical examination, and 12-lead ECG. Patients were considered “symptomatic” when they presented documented unexplained syncope, resuscitated cardiac arrest, or ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation. Unexplained sudden cardiac death (SCD) was defined as a death occurring <1 hour after onset of symptoms in a patient with no underlying cardiac disease or occurring during sleep. In relatives >15 years of age with a normal or type 2 or 3 BrS ECG, an ajmaline (1 mg/kg) challenge was proposed. In view of the risk of arrhythmias, as recommended by Rolf et al, injection of ajmaline was performed over 10 minutes and stopped at significant J-point increase or widening of the QRS interval by >130%.

BrS ECG was defined by the presence of coved ST-segment elevation ≥0.2 mV (type 1 ECG). First-degree relatives included parents, offspring, and siblings. Screened relatives consisted of relatives in whom an ajmaline challenge was not contraindicated or relatives belonging to a family in which a SCN5A mutation had been found in the proband. Affected relatives were defined by the presence of spontaneous or drug-induced type 1 BrS ECG and/or same SCN5A mutation as the proband. Familial forms were defined by the presence of another family member with proved BrS or carrying the same SCN5A mutation as the proband. Sporadic forms were defined as families with no identified family members with BrS. Electrophysiologic studies were performed in symptomatic relatives with spontaneous or drug-induced type 1 ECG. Asymptomatic relatives with type 1 BrS ECG were also investigated until 2006. Annual ECGs were advised in asymptomatic patients with drug-induced type 1 ECG. Patients were provided with a list of drugs able to induce BrS ECG.

Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid was purified from blood samples treated with ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid by standard methods. Molecular characterization of the mutation was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by direct deoxyribonucleic acid sequencing of PCR products using the primers described by Wang et al. Subsequent sequencing reactions of the complete SCN5A coding sequence and the exon–intron junctions were performed using the BigDye Terminator V3.1 kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). PCR products were analyzed using the ABIPRISM TM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The 3′ untranslated region including the polyadenylation signal was also sequenced.

Data were analyzed with SPSS 10 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Chi-square and Student’s t tests were performed when appropriate to test for statistical differences. Analysis of variance was used for multiple comparisons. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

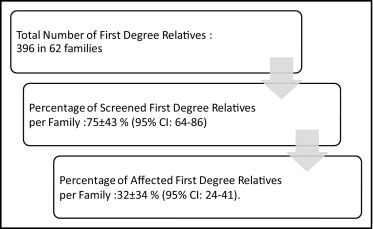

Characteristics of probands are presented in Table 1 . One young symptomatic patient who refused ICD implantation died from nocturnal SCD with documented ventricular fibrillation. The proband’s shocked mother who advised her son to refuse ICD implantation and the first-degree family refused any subsequent screening. The 62 families represented 545 relatives and 488 of them (89%) agreed to participate in the study (mean 7.9 ± 8.6 subjects per family). Mean percentage of screened first-degree relatives per family was 75 ± 43% (95% confidence interval [CI] 64 to 86; Figure 1 ). The 20-year-old son of a proband died from SCD before family screening had been completed.

| Variable | Total (n = 98) | Family Screening Participation | No Family Screening Participation | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 62) | (n = 36) | |||

| Age (years) | 44 ± 13 | 46 ± 14 | 42 ± 12 | NS |

| Men | 76 (76%) | 43 (69%) | 33 (92%) | 0.005 |

| Symptoms | 98 (100%) | 62 (100%) | 36 (100%) | |

| Asymptomatic | 77 (79%) | 45 (73%) | 32 (89%) | NS |

| Syncope | 18 (18%) | 14 (22%) | 4 (11%) | NS |

| Sudden cardiac death | 1 (1%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | NS |

| Aborted sudden cardiac death | 2 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | NS |

| Electrocardiogram | 98 (100%) | 62 (100%) | 36 (100%) | |

| Spontaneous type 1 | 39 (40%) | 26 (42%) | 13 (36%) | NS |

| Drug-induced type 1 | 59 (60%) | 36 (58%) | 23 (64%) | NS |

| Family history of sudden cardiac death | 25 (25%) | 19 (31%) | 6 (17%) | NS |

| Electrophysiologic study | 74 (75%) | 50 (81%) | 24 (67%) | NS |

| Ventricular fibrillation inducibility | 38 (51%) | 31 (62%) | 7 (29%) | 0.01 |

| Implantable cardiac defibrillator | 21 (21%) | 17 (27%) | 4 (11%) | 0.05 |

| Appropriate shocks | 2 (9%) | 2 (12%) | 0 (0%) | NS |

| Inappropriate shocks | 5 (24%) | 4 (24%) | 1 (25%) | NS |

| Hydroquinidine therapy | 18 (18%) | 15 (24%) | 3 (8%) | 0.07 |

| SCN5A genotyping | 67 (68%) | 56 (90%) | 11 (30%) | 0.01 |

| SCN5A mutation | 13 (19%) | 10 (18%) | 3 (27%) | NS |

A spontaneous type 1 BrS ECG was found in 4 of the 488 relatives (0.8%). In the group of relatives in whom ajmaline challenge was performed, the prevalence of affected relatives was 29% (78 cases of 270 tests). ST segment was normal in 73% of these affected relatives and the disease was detected only after ajmaline challenge ( Table 2 ). Mean percentage of affected relatives per family was 27 ± 32% (95% CI 19 to 35) with a higher mean percentage in first-degree relatives (32 ± 34%, 95% CI 24 to 41). Relatives with SCN5A mutation presented a higher rate of normal ECGs (13 of 16, 81%) than probands with SCN5A mutations (2 of 13, 15%). Nineteen relatives underwent electrophysiologic study (2 for syncope, 3 for type 1 BrS ECG, and 14 for familial sudden death) that demonstrated inducible ventricular fibrillation in 6 subjects. Four of these relatives received hydroquinidine and 2 received an ICD. No arrhythmic event occurred during follow-up. Five of 16 patients (31%), from 3 different families, presented with SCN5A mutation (R1913H, F2004L, R1193Q) but did not have a positive finding from the ajmaline challenge. These patients were significantly younger than those with a positive finding from the ajmaline challenge (19 ± 12 vs 45 ± 13 years, p = 0.004). Two relatives from 2 different families in whom a SCN5A mutation was identified in the proband had a positive finding from the ajmaline challenge but no SCN5A mutation. In each of these families, the finding from ajmaline challenge was positive in the proband’s 2 parents, but the SCN5A mutation was present in only 1 parent. One of these 2 families has been previously reported.

| Variable | Total Population (n = 550) | Probands (n = 62) | Affected Relatives (n = 88) | Other Relatives (n = 400) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probands vs Affected Relatives | Affected vs Other Relatives | Probands vs Other Relatives | |||||

| Age (years) | 38 ± 20 | 46 ± 14 | 39 ± 15 | 36 ± 22 | 0.01 | NS | 0.001 |

| Men | 266 (48%) | 43 (69%) | 37 (42%) | 187 (47%) | 0.001 | NS | 0.001 |

| Symptoms | 550 (100%) | 62 (100%) | 88 (100%) | 400 (100%) | |||

| Asymptomatic | 530 (96.3%) | 45 (73%) | 85 (97%) | 400 (100%) | 0.001 | NS | 0.001 |

| Syncope | 16 (2.9%) | 14 (22%) | 2 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.001 | NS | 0.001 |

| Sudden cardiac death | 4 (0.7%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | NS | NS | 0.001 |

| Electrocardiogram | 550 (100%) | 62 (100%) | 88 (100%) | 400 (100%) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Normal | 456 (83%) | 2 (3%) | 64 (73%) | 390 (98%) | |||

| Type 2 | 64 (11%) | 34 (55%) | 20 (23%) | 10 (2%) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Type 1 | 30 (6%) | 26 (42%) | 4 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.001 |

| Sodium channel blocker challenge | 325 (59%) | 55 (87%) | 84 (94%) | 186 (46%) | NS | 0.04 | 0.001 |

| Positive | 134 (41%) | 55 (100%) | 79 (94%) | 0 (0%) | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Negative | 191 (59%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (6%) | 186 (100%) | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| SCN5A genotyping | 197 (36%) | 56 (90%) | 37 (42%) | 104 (26%) | NS | NS | 0.001 |

| SCN5A mutations | 26 (13%) | 10 (18%) | 16 (43%) | 0 (0%) | NS | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Familial forms were found in 66% of subjects. Characteristics of sporadic versus familial forms are listed in Table 3 . SCN5A mutations found in the study population are listed in Table 4 . No SCN5A mutations were found in sporadic forms. Twenty-two of the 41 familial forms included 2 patients. In the other families, the number of affected patients per family was usually 3 or 4 ( Figure 2 ).

| Variable | Total | Sporadic Forms | Familial Forms | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of families | 62 | 21 | 41 | |

| Proband age (years) | 46 ± 14 | 46 ± 14 | 45 ± 14 | NS |

| Men probands | 43 (69%) | 13 (62%) | 30 (73%) | NS |

| Proband symptoms | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 45 (72%) | 18 (86%) | 27 (65%) | NS |

| Syncope | 14 (23%) | 2 (9%) | 12 (30%) | NS |

| Sudden cardiac death | 3 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (5%) | NS |

| Proband electrocardiogram | ||||

| Normal | 2 (4%) | 0 | 2 (5%) | NS |

| Type 2 | 34 (54%) | 15 (71%) | 19 (46%) | 0.03 |

| Type 1 | 26 (42%) | 6 (29%) | 20 (49%) | 0.1 |

| Family history of sudden cardiac death | 21 (34%) | 5 (24%) | 16 (39%) | NS |

| SCN5A genotyping | 56 (90%) | 16 (76%) | 40 (97%) | NS |

| SCN5A mutations | 10 (18%) | 0 | 10 (25%) | 0.02 |

| Relatives screened | 488 (100%) | 114 (23%) | 374 (77%) | — |

| Number screened/family | 7.9 ± 8.6 | 5.3 ± 7.4 | 9.2 ± 8.9 | 0.09 |

| Carriers/family | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 0 | 2.0 ± 2.1 | — |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree