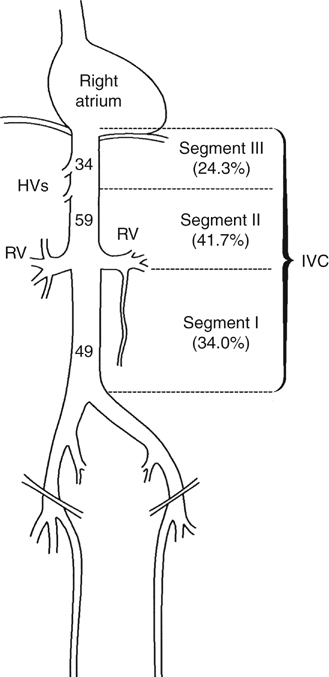

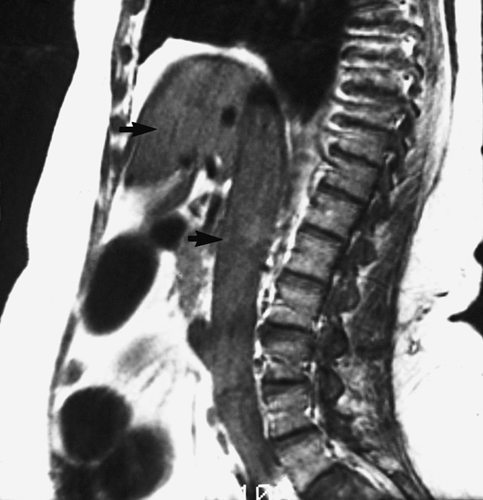

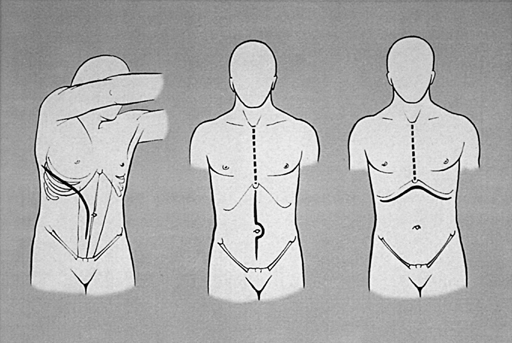

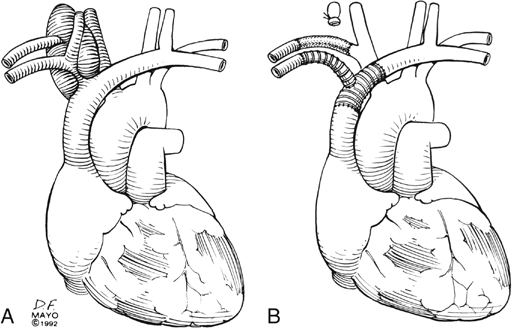

The most common primary tumor of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and superior vena cava (SVC) is leiomyosarcoma. Primary venous leiomyosarcoma involves the IVC in 60% of patients, with three fourths of those involving the suprarenal and infrarenal segments (Figure 1). These tumors are polypoid or nodular, are firmly attached to the vessel wall, and show less intratumor hemorrhage or necrosis than other sarcomas. The most common growth pattern is intraluminal, but the tumor can grow through the vein wall into adjacent structures in advanced cases. Such biologic behavior makes it difficult to differentiate a primary venous leiomyosarcoma from other retroperitoneal sarcomas. Metastatic disease to the lung, liver, kidney, bone, pleura, or chest wall occurs in nearly one half of patients by the time diagnosis is made. Secondary tumors involve the IVC more often than primary tumors. They can affect any segment of the vena cava, and they often infiltrate its wall (Box 1). Some malignancies exhibit intraluminal tumor thrombus as part of their biologic behavior, with renal cell cancer being the most common. Such renal cell cancers tend to be large (>4.5 cm), and they more often involve the right kidney. Thrombus is isolated to the renal vein–caval confluence in 50%; another 40% have thrombus in the suprarenal IVC, and 10% have thrombus extending into the right heart. If a tumor proves to be localized and there is no evidence of metastatic disease, preoperative risk assessment is done, which includes cardiopulmonary assessment. Patient performance status influences the decision to operate. Those who are bedridden or need significant help in daily care are not candidates for operation. CT and MRI are the two most useful studies because assessment of local extent of the tumor is done by axial, coronal, and sagittal images. Venous phase imaging has all but eliminated venacavography as a diagnostic study, unless intraluminal biopsy is needed. The deep veins of the lower extremities are imaged by US to exclude occult bland DVT. MRI is particularly useful in defining the extent of intracaval tumor thrombus, and transesophageal echocardiography is added when there is concern of thrombus extension into the right heart (Figure 2). In patients with renal cell cancer and intracardiac tumor thrombus the approach is through a median sternotomy and midline abdominal incision, though occasionally the sternotomy is combined with a bilateral subcostal incision. The infrarenal IVC is best approached through a midline incision, which allows access to the common iliac veins for inflow control (Figure 3). Most patients with malignant involvement of the SVC are treated by stenting, but for the rare patient in whom tumor-free margins are anticipated, the SVC can be replaced using either femoral vein, spiral saphenous vein, or synthetic graft. For the latter, we prefer externally supported expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) grafts (Figure 4). Should the tracheal or esophageal wall require resection, femoral vein is a good alternative.

Primary and Secondary Vena Cava Tumors

Tumor Types

Evaluation

Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine