Patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) can require antiarrhythmic drugs to manage arrhythmias and prevent device shocks. We sought to determine the prevalence, clinical correlates, and institutional variation in the use of antiarrhythmic drugs over time after ICD implantation. From the ICD Registry (2006 to 2011), we analyzed the trends in the use of antiarrhythmic agents prescribed at hospital discharge for patients undergoing first-time ICD placement. The patient, provider, and facility level variables associated with antiarrhythmic use were determined using multivariate logistic regression models. A median odds ratio was calculated to assess the hospital-level variation in the use of antiarrhythmic drugs. Of the cohort (n = 500,995), 15% had received an antiarrhythmic drug at discharge. The use of class III agents increased modestly (13.9% to 14.9%, p <0.01). Amiodarone was the most commonly prescribed drug (82%) followed by sotalol (10%). Among the subgroups, the greatest increase in prescribing was for patients who had received a secondary prevention ICD (26% in 2006% and 30% in 2011, p <0.01) or with a history of ventricular tachycardia (23% to 27%, p <0.01). The median odds ratio for antiarrhythmic prescription was 1.45, indicating that 2 randomly selected hospitals would have had a 45% difference in the odds of treating identical patients with an antiarrhythmic drug. In conclusion, antiarrhythmic drug use, particularly class III antiarrhythmic drugs, is common among ICD recipients at hospital discharge and varies by hospital, suggesting an influence from local treatment patterns. The observed hospital variation suggests a role for augmentation of clinical guidelines regarding the use of antiarrhythmic drugs for patients undergoing implantation of an ICD.

Despite the potential for adverse events, little is known about the prevalence and patterns of use of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients who have received implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) therapy. The estimates of adjunctive antiarrhythmic therapy for ICD recipients have come from early retrospective case series of patients with sustained ventricular arrhythmias and have varied widely from 40% to 70% of ICD recipients. In clinical trials performed in the late 1990s, approximately 20% of ICD recipients also received antiarrhythmic therapy. Despite the advent of novel antiarrhythmic drugs and the changing indications for ICDs, little contemporary evidence is available regarding the real-world prevalence and patterns of antiarrhythmic use in ICD recipients. The aim of the present study was to characterize the contemporary national patterns of antiarrhythmic drug use in patients receiving ICD therapy in a large national United States registry.

Methods

The subjects were enrolled from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s ICD Registry. Collection of data in the ICD Registry has been mandated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as a stipulation of payment for all primary prevention ICD implantations in the United States since 2006. The registry captures detailed clinical, demographic, and procedural information and includes medications prescribed at discharge using standardized data elements and definitions. The Data are submitted by the participating hospitals using certified software. Data quality is examined using a formal data quality reporting process. Institutions with submissions passing the inclusion and exclusion quality criteria for data completeness were included in the data analytic file used for the present analysis. All patients in the ICD Registry who had received a first time (de novo) ICD (including cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator [CRT-D]) from January 1, 2006 to September 30, 2011 (n = 500,995) were included in the present analysis.

The main outcome of interest was the prescription of an antiarrhythmic medication at discharge, classified as follows: class IA (quinidine, disopyramide, procainamide), class IB (mexiletine), class IC (propafenone, flecainide), and class III (amiodarone, sotalol, dofetilide). Information on dronedarone was not routinely captured by the data collection forms used for the ICD Registry. β Blockers and calcium channel blockers (Vaughan-Williams class II and IV, respectively) were not considered antiarrhythmic drugs, because these drugs are more often prescribed for indications other than arrhythmia.

The patient characteristics were collected in the ICD Registry and included as potential correlates of the prescription of antiarrhythmic drug at discharge: year of implant, age, gender, race, reason for admission (procedure only, hospitalized with a cardiac indication, or hospitalized with a noncardiac indication), insurance payer, syncope, family history of sudden death, history of heart failure, New York Heart Association class, history of cardiac arrest, atrial fibrillation or flutter, ventricular tachycardia (VT), cardiac transplantation, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, ischemic heart disease, previous myocardial infarction, previous coronary bypass surgery, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, previous valvular surgery, previous pacemaker implantation, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, hypertension, renal failure requiring dialysis, ejection fraction, QRS duration, PR interval, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, serum sodium, systolic blood pressure, ICD indication (primary, secondary), and ICD type (single, dual chamber, CRT-D). The provider characteristics and implanting physician’s training (board-certified or nonboard-certified electrophysiologist, surgeon, pediatric cardiologist, Heart Rhythm Society-credentialed, none of these) were also collected. The facility characteristics that were collected included geographic location, owner, urban/rural location, number of patient beds, and teaching status. We used the US Census division as a geographic variable.

All baseline variables collected in the ICD Registry were analyzed and compared between the patients with and without an antiarrhythmic prescription. Univariate associations were examined using t tests for continuous variables and chi-square testing for categorical variables. The factors independently associated with the use of antiarrhythmic drugs were identified using hierarchical logistic regression analysis, accounting for the potential clustering of patients among hospitals using a backward selection method. Most of the covariates had low rates of missing values (<1%); in such cases, the missing values were imputed as the median for continuous variables and the most common category for the categorical variables for the model analyses. For the few variables with missing rates >1%, the missing values were considered as a category for categorical variables. For continuous variables, a dummy variable indicating the missing values was created, and the missing values were imputed as the median. Both variables were considered as candidate variables in all multivariate models.

We prespecified several subgroups of interest to stratify our analysis of antiarrhythmic prescription: primary prevention ICD, secondary prevention ICD, atrial fibrillation or flutter, the absence of atrial fibrillation or flutter, VT, and ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. In addition, we included a subgroup of patients without any clearly documented indication for antiarrhythmic therapy (i.e., primary prevention ICD indication and absence of atrial fibrillation or VT).

To examine the prescription of antiarrhythmic at discharge during different periods, we examined the rate of prescription of antiarrhythmic agents in each year and tested the trend using the Cochran-Armitage trend test for different types antiarrhythmic medications and among the different subgroups.

To assess the institutional-level variation in use, we assessed the distributions and interquartile ranges of discharge antiarrhythmic prescriptions in the entire sample and in each year. To quantify the extent to which the variation in antiarrhythmic drug use was explained by hospital level effects, the hospital-specific median odds ratio (MOR) was determined, adjusting for the patient, clinical, and demographic characteristics. The MOR will always be >1.0. An MOR of 1.0 signifies no clustering effects, and an MOR of 2.0 indicates that an individual patient would have twofold greater odds of receiving an antiarrhythmic medication at discharge if cared for at another randomly selected hospital.

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis Systems statistical package, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and approved by the Yale Human Subjects Investigations Committee. Variables with p <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the entire cohort, 15.1% received an antiarrhythmic drug at discharge. The patients receiving an antiarrhythmic drug were older and more likely to have a history of cardiac arrest, atrial fibrillation or flutter, VT, or syncope ( Table 1 ). They also were more likely to have received an ICD for secondary prevention or to have received a dual-chamber device. However, they were less frequently prescribed an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker or β blocker. Modest differences were present in the prevalence of coexisting illnesses between the 2 groups.

| Characteristic | Antiarrhythmic Use at Discharge | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 425,279) | Yes (n = 75,716) | ||

| Year of implantation | <0.01 | ||

| 2006 | 15.1 | 14.9 | |

| 2007 | 18.3 | 17.8 | |

| 2008 | 18.4 | 17.8 | |

| 2009 | 18.5 | 18.3 | |

| 2010 | 17.6 | 18.2 | |

| 2011 | 12.0 | 13.0 | |

| Age (yrs) | 68 (49–87) | 71 (55–87) | <0.01 |

| Female gender | 28.2 | 23.7 | <0.01 |

| Race | <0.01 | ||

| White | 80.9 | 85.5 | |

| Black | 14.2 | 10.3 | |

| Other | 4.9 | 4.2 | |

| Reason for hospitalization | <0.01 | ||

| Admitted for ICD implant | 64.1 | 41.9 | |

| Hospitalized, cardiac | 17.2 | 25.8 | |

| Hospitalized, noncardiac | 16.2 | 29.0 | |

| NYHA class | <0.01 | ||

| I | 12.6 | 14.0 | |

| II | 35.7 | 31.3 | |

| III | 48.0 | 48.8 | |

| IV | 3.6 | 5.9 | |

| Previous syncope | 17.7 | 22.8 | <0.01 |

| Family history of sudden death | 4.5 | 3.7 | <0.01 |

| Previous heart failure | 78.4 | 75.6 | <0.01 |

| Cardiac arrest | 7.9 | 19.4 | <0.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 26.8 | 58.5 | <0.01 |

| VT | 29.8 | 52.9 | <0.01 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 62.5 | 65.6 | <0.01 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 50.7 | 52.6 | <0.01 |

| Previous coronary bypass | 32.1 | 33.5 | <0.01 |

| Previous percutaneous intervention | 32.5 | 31.4 | <0.01 |

| Previous pacemaker | 10.3 | 13.4 | <0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 14.5 | 16.2 | <0.01 |

| Chronic lung disease | 22.3 | 25.0 | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 37.9 | 36.6 | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 76.9 | 78.2 | <0.01 |

| Renal failure requiring dialysis | 3.7 | 4.8 | <0.01 |

| Diagnostic studies | |||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 27.9 ± 10.9 | 29.0 ± 12.1 | <0.01 |

| Electrophysiologic study performed | 13.2 | 15.4 | <0.01 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 123.7 ± 33.2 | 126.8 ± 34.0 | <0.01 |

| PR interval (ms) | 179.2 ± 41.3 | 187.7 ± 47.4 | <0.01 |

| ACE inhibitor (any) | 61.9 | 57.7 | <0.01 |

| ARB | 16.0 | 13.7 | <0.01 |

| β Blocker (any) | 87.0 | 81.5 | <0.01 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 1.2 | <0.01 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 23.6 ± 13.5 | 25.3 ± 14.4 | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 130.7 ± 22.5 | 130.0 ± 22.6 | <0.01 |

| ICD characteristic | |||

| Primary prevention indication | 84.9 | 66.8 | <0.01 |

| ICD type | <0.01 | ||

| Single chamber | 24.1 | 14.6 | |

| Dual chamber | 39.7 | 49.0 | |

| Biventricular | 36.2 | 36.4 | |

| Training of implanting physician | <0.01 | ||

| Board-certified electrophysiologist | 17.5 | 17.0 | |

| Nonboard-certified electrophysiologist | 58.2 | 57.1 | |

| Surgeon | 7.9 | 7.3 | |

| Pediatric cardiologist | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

| Credentialed ∗ | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| None of these | 6.7 | 7.7 | |

| Hospital characteristics | |||

| Geographic location † | <0.01 | ||

| New England | 4.1 | 3.1 | |

| Mid-Atlantic | 14.1 | 12.1 | |

| South-Atlantic | 22.5 | 21.2 | |

| East North Central | 17.5 | 18.2 | |

| East South Central | 7.4 | 8.2 | |

| West North Central | 7.5 | 7.6 | |

| West South Central | 10.9 | 11.8 | |

| Mountain | 4.5 | 4.5 | |

| Pacific | 8.4 | 9.8 | |

| Owner | |||

| Public | 9.5 | 9.4 | |

| Not-for-profit | 74.1 | 73.5 | |

| Private | 13.2 | 13.8 | |

| Location | <0.01 | ||

| Rural | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Urban | 96.4 | 96.1 | |

| Patient beds (n) | 474.0 ± 292.3 | 461.2 ± 282.7 | <0.01 |

| Teaching status (teaching) | 27.3 | 27.4 | <0.01 |

∗ Credentialed referred to an alternative pathway for nonelectrophysiologist physicians to be credentialed to perform ICD implants; it was strictly voluntary and has subsequently expired such that no additional physicians will be characterized as credentialed through this pathway.

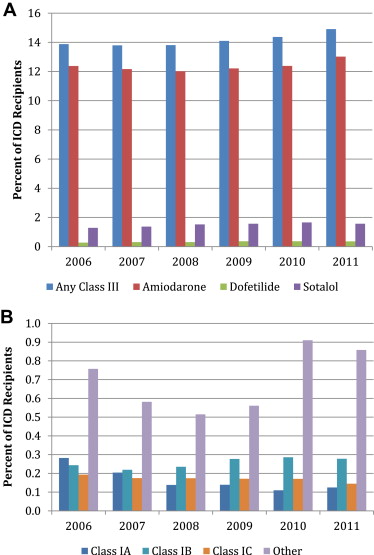

Of the antiarrhythmic drugs used, the class III agents (14.1% of cohort and 93.3% of all antiarrhythmic drugs) were the most commonly prescribed. Of these, amiodarone was the most commonly prescribed (81.5% of all antiarrhythmics) followed by sotalol (9.9%; Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 1 ).

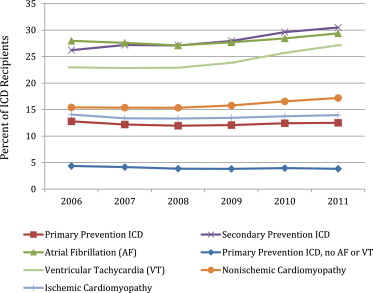

From 2006 to 2011, a modest increase occurred in antiarrhythmic prescriptions (15.0% to 16.1%, p <0.01), with greatest increase for patients who had received an ICD for secondary prevention (26.2% to 30.5%, p <0.01) or with a history of VT (23.0% to 27.1%, p <0.01; Figure 2 ). Also, an increase occurred in the use of antiarrhythmic drugs among patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy (15.4% to 17.2%, p <0.01) but not in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy or those receiving primary prevention ICD or CRT-D therapy. Although a modest increase in use was observed for patients with atrial fibrillation (28.0% to 29.4%, p <0.01), a comparable increase in use was also observed for those without atrial fibrillation (9.1% to 9.7%, p <0.01). Among the patients with a primary prevention ICD and without a history of atrial fibrillation or VT, a small decline occurred in antiarrhythmic prescriptions (4.4% to 3.8%, p <0.01).

From 2006 to 2011, a modest increase was seen in the use of class III drugs (13.9% to 14.9%, p <0.01), with minimal changes in class I use. Each of the class III drugs was significantly more likely to be prescribed in 2011 than in 2006.

The patient, provider, and facility level variables associated with antiarrhythmic prescriptions are listed in Table 2 . The patients who were acutely hospitalized for cardiac or noncardiac indications were more likely to be prescribed antiarrhythmic therapy at discharge than were patients electively hospitalized for ICD implantation. The other patient characteristics associated with increased antiarrhythmic prescription included atrial fibrillation or flutter, a history of cardiac arrest, and VT. Compared with patients whose ICDs were implanted by an electrophysiologist, those whose ICD was implanted by physicians other than electrophysiologists were more likely to be discharged with an antiarrhythmic agent. The characteristics associated with a lower likelihood of antiarrhythmic prescription are also listed in Table 2 . These included black race and renal failure requiring dialysis. Patients undergoing implantation of a primary prevention ICD were less likely to receive an antiarrhythmic drug than were patients who had received an ICD for secondary prevention. Also, patients who had received a single-chamber ICD were less likely to receive an antiarrhythmic drug prescription than were patients who had received a dual-chamber or CRT-D device. Significant regional differences in use were found when stratified by US Census division.

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||

| 2006 | Reference | ||

| 2007 | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | 0.01 |

| 2008 | 0.93 | 0.91–0.96 | <0.01 |

| 2009 | 0.96 | 0.94–0.99 | 0.01 |

| 2010 | 1.04 | 1.01–1.07 | 0.02 |

| 2011 | 1.11 | 1.07–1.14 | <0.01 |

| Age | 1.002 | 1.001–1.003 | <0.01 |

| Female gender | 0.91 | 0.89–0.92 | <0.01 |

| Race | |||

| White | Reference | ||

| Black | 0.87 | 0.85–0.90 | <0.01 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.88–0.95 | <0.01 |

| Reason for hospitalization | |||

| Elective for procedure | Reference | ||

| Hospitalized, cardiac | 1.57 | 1.53–1.60 | <0.01 |

| Hospitalized, noncardiac | 1.72 | 1.68–1.76 | <0.01 |

| Previous syncope | 0.86 | 0.84–0.88 | <0.01 |

| Family history of sudden death | 0.91 | 0.87–0.95 | <0.01 |

| Previous heart failure | 0.96 | 0.94–0.98 | <0.01 |

| NYHA class | |||

| I | Reference | ||

| II | 0.99 | 0.96–1.02 | 0.57 |

| III | 1.06 | 1.02–1.09 | <0.01 |

| IV | 1.22 | 1.16–1.28 | <0.01 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1.57 | 1.53–1.62 | <0.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 3.90 | 3.83–3.97 | <0.01 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 1.97 | 1.93–2.01 | <0.01 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.09 | 1.06–1.12 | <0.01 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1.06 | 1.04–1.08 | <0.01 |

| Previous coronary bypass | 0.93 | 0.91–0.95 | <0.01 |

| Previous percutaneous intervention | 0.95 | 0.94–0.97 | <0.01 |

| Previous valvular surgery | 1.18 | 1.15–1.21 | <0.01 |

| Previous pacemaker | 0.96 | 0.93–0.98 | <0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.95 | 0.92–0.97 | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.92 | 0.90–0.93 | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99 | <0.01 |

| Renal failure requiring dialysis | 0.88 | 0.84–0.92 | <0.01 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 0.995 | 0.994–0.996 | <0.01 |

| QRS duration (per 10 ms) | 1.025 | 1.022–1.028 | <0.01 |

| PR interval (per 10 ms) | 1.030 | 1.027–1.032 | <0.01 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.06 | 1.05–1.07 | <0.01 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (per 10 mg/dl) | 1.012 | 1.006–1.019 | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure (per 10 mm Hg) | 0.994 | 0.990–0.998 | <0.01 |

| Primary prevention indication | 0.56 | 0.55–0.58 | <0.01 |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator type | |||

| CRT-D | Reference | ||

| Single chamber | 0.63 | 0.61–0.65 | <0.01 |

| Dual chamber | 1.23 | 1.20–1.25 | <0.01 |

| Training of implanting physician | |||

| Board-certified electrophysiologist | Reference | ||

| Nonboard-certified electrophysiologist | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | 0.31 |

| Surgeons | 1.23 | 1.15–1.32 | <0.01 |

| Pediatric cardiologist | 0.87 | 0.60–1.26 | 0.45 |

| Credentialed ∗ | 1.12 | 1.08–1.17 | <0.01 |

| None of these | 1.08 | 1.03–1.12 | <0.01 |

| Geographic location † | |||

| Pacific | Reference | ||

| New England | 0.62 | 0.55–0.71 | <0.01 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 0.73 | 0.66–0.80 | <0.01 |

| South-Atlantic | 0.85 | 0.79–0.93 | <0.01 |

| East North Central | 0.90 | 0.83–0.98 | 0.01 |

| East South Central | 1.18 | 1.06–1.32 | <0.01 |

| West North Central | 0.91 | 0.82–1.00 | 0.05 |

| West South Central | 1.04 | 0.95–1.13 | 0.44 |

| Mountain | 0.84 | 0.75–0.94 | <0.01 |

| No. of patient beds (per 10 beds) | 0.998 | 0.997–0.999 | <0.01 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree