The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence and prognosis of patients incidentally diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HC). We studied 380 consecutive patients with HC (49.3 ± 17.2 years; 65% men) for a median of 58 months (range 6 to 454). The patients were divided into 2 groups: those incidentally diagnosed from routine examination findings (precordial murmur and/or abnormal electrocardiographic findings) and those diagnosed either because of symptomatic status or by screening because of a family history of HC. Those patients who had been incidentally diagnosed constituted 29.2% of our study cohort. Although overall mortality did not differ between the 2 groups (p = 0.12), the patients diagnosed either because of symptoms or a family history tended to have at least a 4.5-fold greater risk of cardiovascular death (relative risk 4.5, 95% confidence interval 1.04 to 19.6, p = 0.04) and a 4.22 greater risk of sudden death (relative risk 4.22, 95% confidence interval 1.0 to 18.22, p = 0.04). Despite the greater sudden death mortality among the nonincidentally diagnosed patients, no statistically significant difference was found concerning the sudden death risk factor frequency (p = 0.96) between the 2 groups. In conclusion, the discrepancy between the low numbers of patients reported by published registries and the relatively high prevalence of the disease in the general population can be attributed to the large number of patients who remain asymptomatic, even throughout their life, awaiting an accidental diagnosis. Those patients with an incidental diagnosis have a more benign course, as shown by the total cardiovascular and composite sudden death mortality. A high level of awareness and suspicion for HC among physicians is essential for clinical recognition of such patients.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HC) is probably the most heterogeneous disease in clinical cardiology, in terms of phenotypic presentation, symptoms, and outcome. Its clinical course spans from a fully asymptomatic state to severe cardiovascular manifestations, including heart failure, syncope, stroke, and sudden death. The disease affects 1 in 500 people in the general population. Nevertheless, a large number of patients evade clinical recognition by remaining asymptomatic. In such patients, the diagnosis of HC is often first made incidentally during a routine medical examination. Therefore, we performed a retrospective, observational study of a large cohort of patients with HC from Northern Greece to assess the prevalence and clinical course of incidentally diagnosed HC.

Methods

From February 1992 to March 2009, 380 consecutive patients with documented HC were assessed in AHEPA Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece and were followed up at our institution. The diagnosis of HC was determined by the echocardiographic appearance of a left ventricular maximum wall thickness ≥15 mm, in the absence of any other cause capable of producing such hypertrophy. HC was also considered present in patients with a maximum wall thickness of 13 or 14 mm and a positive family history for HC and/or electrocardiographic changes compatible with HC. Patient follow-up began at the point at which the first diagnosis had been made, even if the diagnosis preceded the baseline patient evaluation in our clinic. The follow-up period was considered the interval from the initial diagnosis to death and/or other end point or, in surviving patients, to the most recent evaluation. The patients were examined every 12 months, except as otherwise indicated. Our study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional ethics committee approved the research protocol, and the study participants provided written informed consent at the first evaluation.

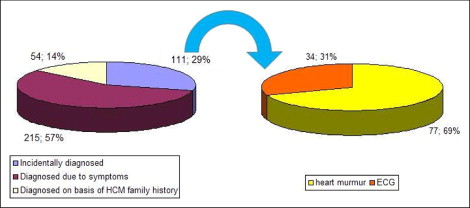

The reasons leading to referral to our institution and, ultimately, to the echocardiographic studies that diagnosed HC were acquired by retrospective review of the patients’ medical records and, if necessary, by direct telephone interviews with the patients. Using the reason leading to the diagnosis, the participants were divided into 2 groups. In the first group (n = 111, 29.2%), we included asymptomatic patients whose HC was diagnosed incidentally by objective routine examination findings (precordial murmur and/or abnormal electrocardiographic findings). In the second group (n = 269, 70.8%), we enrolled patients whose HC had been diagnosed either because they were symptomatic (development of symptoms, including dyspnea, angina or chest pain, palpitations, and/or an acute cardiovascular event manifestation [eg, syncope, atrial fibrillation, stroke, cardiac arrest, acute coronary syndrome]) or from because they had undergone screening owing to a family history of HC.

The baseline patient evaluation included the personal and family history, a clinical evaluation, a 12-lead electrocardiogram, transthoracic echocardiography, 24-hour electrocardiographic monitoring, and an upright treadmill exercise stress test. The echocardiographic studies were performed using commercially available equipments and included M-mode, 2-dimensional, pulsed- and continuous-wave Doppler echocardiography, and tissue Doppler imaging, because at the time it was available in our clinic. Segmental left ventricular hypertrophy was measured in 2-dimensional echocardiography parasternal short-axis views, according to previously described methods. Standard M-mode measurements were made according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography. The basal subaortic gradient was measured using continuous-wave Doppler echocardiography. The patients also underwent a symptom-limited upright exercise test using the Bruce protocol. Finally, 24-hour Holter electrocardiographic recordings were made while the patients performed their ordinary daily activities.

On the basis of previously published data, 5 noninterventional clinical features were defined as risk factors for sudden death: (1) syncope, (2) premature sudden death, (3) recurrent episodes of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, (4) an abnormal blood pressure response, and (5) severe hypertrophy.

Overall mortality, total cardiovascular mortality, and the prevalence of sudden death and its equivalents were considered the primary end points of our study. Overall mortality referred to deaths from any cause and cardiovascular mortality to death from heart failure, stroke, or sudden death. Sudden death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, documented ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, and appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator discharge formed the composite sudden death and surrogates end point. All recorded events were identified either by telephone interview with the patients or by systemic review of death certificates, hospital release forms, and defibrillator record reports. No patient withdrew from the study during the study period.

Normality plots were tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test for p >0.05. The distributions of variables in the study cohort are summarized as the mean ± SD and as the median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data. To determine whether the patients who had been incidentally diagnosed with HC differed from the others in terms of one or more HC-related demographic, clinical, or echocardiographic variables, the chi-square test was used when the variable was categorical and the unpaired Student t test when the variable was continuous and normally distributed. The Mann-Whitney U test was used as a nonparametric alternative.

Survival curves were constructed according to the Kaplan-Meier method. A comparison of the survival curves between the incidentally and nonincidentally diagnosed patients was made using the log-rank test. We also performed comparisons after adjustment for gender and age. The 5-year survival from all-cause or specific mortality was indexed for each subgroup. To assess the role of incidental or nondiagnosis as a possible risk factor for death, cardiovascular death, or sudden death, a set of univariate Cox proportional hazard models were fit to the data. Multivariate Cox regression analysis using the standard 5 noninterventional sudden death risk factors as covariates and incidental diagnosis as a stratifying factor was used to assess the survival rates of the incidentally or not diagnosed patients in the presence of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 risk factors. p Values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Most of the statistical estimates were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

Of the entire HC population followed up at our institution (n = 380), 111 patients had been incidentally diagnosed (29.2%). A routine clinical examination was performed as a part of preparticipation screening for 20 recreational athletes (5.2% of the overall study group), as preoperative testing for noncardiac general surgery for 18 patients (4.7%), and as a prearranged medical evaluation (military service, professional licensure) for 10 patients (2.6%). An additional 12 patients hospitalized for noncardiac reasons were referred to our laboratory because of a pathologic murmur or electrocardiographic findings. Of the remaining 51 patients (46% of those incidentally diagnosed), the diagnosis was elicited through an annual routine general checkup ( Figure 1 and Table 1 ).

| Variable | Overall Population (n = 380) | Incidentally Diagnosed | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 111) | No (n = 269) | |||

| Age at initial evaluation (years) | 53.6 ± 16.3 | 49.5 ± 17.5 | 55.3 ± 15.5 | 0.003 ⁎ |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 49.3 ± 17.2 | 45 ± 18.1 | 51.1 ± 16.5 | 0.003 ⁎ |

| Men | 247 (65%) | 83 (75%) | 164 (61%) | 0.01 ⁎ |

| Referral from other center to ours | 232 (61%) | 73 (66%) | 159 (59%) | 0.25 |

| Follow-up (months) | 58 (6–454) | 60 (8–454) | 58 (6–357) | 0.18 |

| Diagnosed by | 111 (29%) | — | — | — |

| Abnormal electrocardiographic findings | 77 (20%) | 77 (69%) | — | |

| Precordial murmur | 34 (9%) | 34 (31%) | — | |

| Diagnosed by symptoms | 151 (40%) | — | 151 (56%) | — |

| Angina pectoris/angina-like | 49 (13%) | 49 (18%) | ||

| Dyspnea | 92 (24%) | 89 (34%) | ||

| Palpitations | 10 (3%) | 10 (4%) | ||

| Diagnosed because of major event | 64 (17%) | — | 64 (24%) | — |

| Syncope/presyncope | 27 (7%) | 27 (10%) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation (permanent/paroxysmal) | 21 (6%) | 21 (8%) | ||

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | ||

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.4%) | ||

| Stroke | 6 (2%) | 6 (2%) | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 6 (2%) | 6 (2%) | ||

| Diagnosed from family screening | 54 (14%) | — | 54 (20%) | — |

| Family history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 124 (33%) | 24 (22%) | 100 (37%) | 0.004 ⁎ |

| Echocardiographic characteristics | ||||

| Left ventricular outflow tract peak pressure gradient >30 mm Hg | 94 (25%) | 26 (23%) | 68 (25%) | 0.79 |

| Left atrial size (cm) | 4.21 ± 0.75 | 4.08 ± 0.67 | 4.26 ± 0.77 | 0.04 ⁎ |

| Mid-anteroseptum thickness (diastole) (cm) | 2.0 ± 0.63 | 2.24 ± 0.86 | 1.9 ± 0.49 | 0.009 ⁎ |

| Posterior wall diameter (diastole) (cm) | 1.07 ± 0.33 | 1.08 ± 0.38 | 1.07 ± 0.32 | 0.89 |

| New York Heart Association class (during follow-up) | ||||

| I | 162 (43%) | 73 (66%) | 89 (33%) | <0.001 ⁎ |

| II | 165 (43%) | 30 (27%) | 127 (47%) | <0.001 ⁎ |

| III–IV | 53 (14%) | 8 (7%) | 53 (20%) | <0.001 ⁎ |

The patients who were incidentally diagnosed were more likely to be men (74.8% vs 61%, p = 0.01), and were ≥5 years younger than the patients diagnosed because of symptoms or a family history, both at the initial diagnosis and at the first evaluation in our center (45 ± 18.1 vs 51 ± 16.5 years, p = 0.003, and 49.5 ± 17.5 vs 55.3 ± 15.5 years, p = 0.003, respectively). Concerning their symptomatic status during follow-up, 7 of 10 cases discovered incidentally were graded as New York Heart Association class I (73 of 111, 65.8%). In contrast, only 33.1% of the nonincidentally diagnosed cases (89 of 269 patients) belonged to the same New York Heart Association class (p <0.001). Dyspnea remained, by far, the dominating first symptom of the “nonincidental” group (89 of 269, 33.1%). Despite the obvious differences in their clinical manifestations, the 2 groups had nonsignificant differences in echocardiographic data ( Table 1 ).

During a median follow-up period of 58 months (range 6 to 454; p = 0.18 between groups), 23 patients died; 20 were of cardiovascular etiology and 3 were unrelated to the HC substrate ( Table 2 ). The 5-year survival rate from all-cause mortality was 97.4% (95% confidence interval 95.6 to 99.1). The 5-year survival rate from cardiovascular death was 97.6% (95% confidence interval 95.8 to 99.3). Finally, the 5-year survival rate from sudden death (7 patients), ventricular tachycardia (3 patients), implantable cardioverter-defibrillator discharge (4 patients), and resuscitated cardiac arrest (5 patients) was 96.7% (95% confidence interval 94.5 to 98.9; Figure 2 ).

| Variable | Overall Population (n = 380) | Incidentally Diagnosed | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 111) | No (n = 269) | |||

| Death from any cause | 23 (6%) | 4 (4%) | 19 (7%) | 0.12 |

| Cardiovascular death | 20 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 18 (7%) | 0.04 ⁎ |

| Sudden death (and equivalents) | 19 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 17 (6%) | 0.04 ⁎ |

| Risk factors for sudden death | 0.96 | |||

| 0 | 252 (66%) | 76 (69%) | 176 (65%) | |

| 1 | 84 (22%) | 22 (20%) | 62 (23%) | |

| 2 | 31 (8%) | 9 (8%) | 22 (8%) | |

| 3 | 9 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 6 (2%) | |

| 4 | 4 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Risk factors for sudden death | ||||

| Syncope | 51 (13%) | 6 (5%) | 45 (17%) | 0.003 ⁎ |

| Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia | 32 (8%) | 7 (6%) | 25 (9%) | 0.42 |

| Abnormal blood pressure response | 47 (12%) | 17 (15%) | 30 (11%) | 0.30 |

| Maximum wall thickness >3.0 mm | 30 (8%) | 12 (11%) | 18 (7%) | 0.13 |

| Family history of sudden death | 44 (12%) | 13 (12%) | 31 (12%) | 1.0 |

| Progression to end-stage hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 25 (7%) | 3 (3%) | 22 (8%) | 0.02 ⁎ |

| Medication (during follow-up) | 281 (74%) | 67 (60%) | 214 (80%) | <0.001 ⁎ |

| β Blockers | 192 (51%) | 46 (41%) | 146 (54%) | 0.02 ⁎ |

| Disopyramide | 10 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 8 (3%) | 0.66 |

| Verapamil | 20 (5%) | 4 (4%) | 16 (6%) | 0.46 |

| Warfarin | 44 (12%) | 9 (8%) | 35 (13%) | 0.22 |

| Amiodarone | 30 (8%) | 10 (9%) | 20 (7%) | 0.72 |

| Cardioverter defibrillator implantation | 26 (7%) | 7 (6%) | 19 (7%) | 1.0 |

| Stroke incidence | 30 (8%) | 5 (5%) | 25 (9%) | 0.14 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree