aFrom the IAC Standards and Guidelines for Vascular Testing Accreditation (updated 15 June, 2013). For subsequent updates, see http://intersocietal.org/vascular/

The physician interpretation must be available within 2 working days of the examination, and the final signed report should be available within 4 working days. All records related to the examination, including the final report, must be retained in accordance with local, state, and federal guidelines for medical records—generally 5 to 7 years for adult patients.

Reporting Terminology

It is stating the obvious to advocate the use of standard medical nomenclature and clear language in vascular laboratory reports, but achieving this goal requires effort by both technologists and physicians. For example, the terminology for describing the venous system in the lower limbs has been problematic.3,4 Although many vascular laboratories use the historically correct term “superficial femoral vein” to describe the main deep vein of the thigh, experience has shown that some physicians are not aware that this is, in fact, a deep vein.5 Therefore, they may not consider acute thrombosis of this vein as a serious problem requiring immediate treatment. In order to avoid errors in patient management related to this misunderstanding, it is now recommended that the superficial femoral vein be referred to simply as the femoral vein, along with the common femoral and deep femoral veins.

Other potential sources of confusion are abbreviations and eponyms. Nonvascular specialists may not be familiar with the common abbreviations used in the vascular laboratory, so it a good policy to provide definitions of any abbreviations used in a report. For the same reason, eponyms should be avoided. For example, the terms “Giacomini’s vein” and “Leonardo’s vein” sound erudite, but posterior thigh circumflex vein and posterior accessory great saphenous vein are more descriptive.

The physician’s impression or conclusion should address the specific clinical indications for the test. If a patient is referred for workup of a neck bruit, then the final interpretation of the carotid examination should state whether or not a source for a bruit was identified. If the purpose of a venous evaluation is to look for evidence of chronic venous insufficiency, then it is not adequate to conclude that deep venous thrombosis is not identified—the presence or absence of reflux must also be noted. In addition, an effort should be made to avoid vague terms such as “moderate stenosis” or “functional occlusion” that have no standard definitions. Finally, after the interpreting physician has addressed the indications for the test, she or he should note how the findings compare with previous tests and offer recommendations for further follow-up, whenever possible.

SAMPLE REPORTS

Preliminary Reports

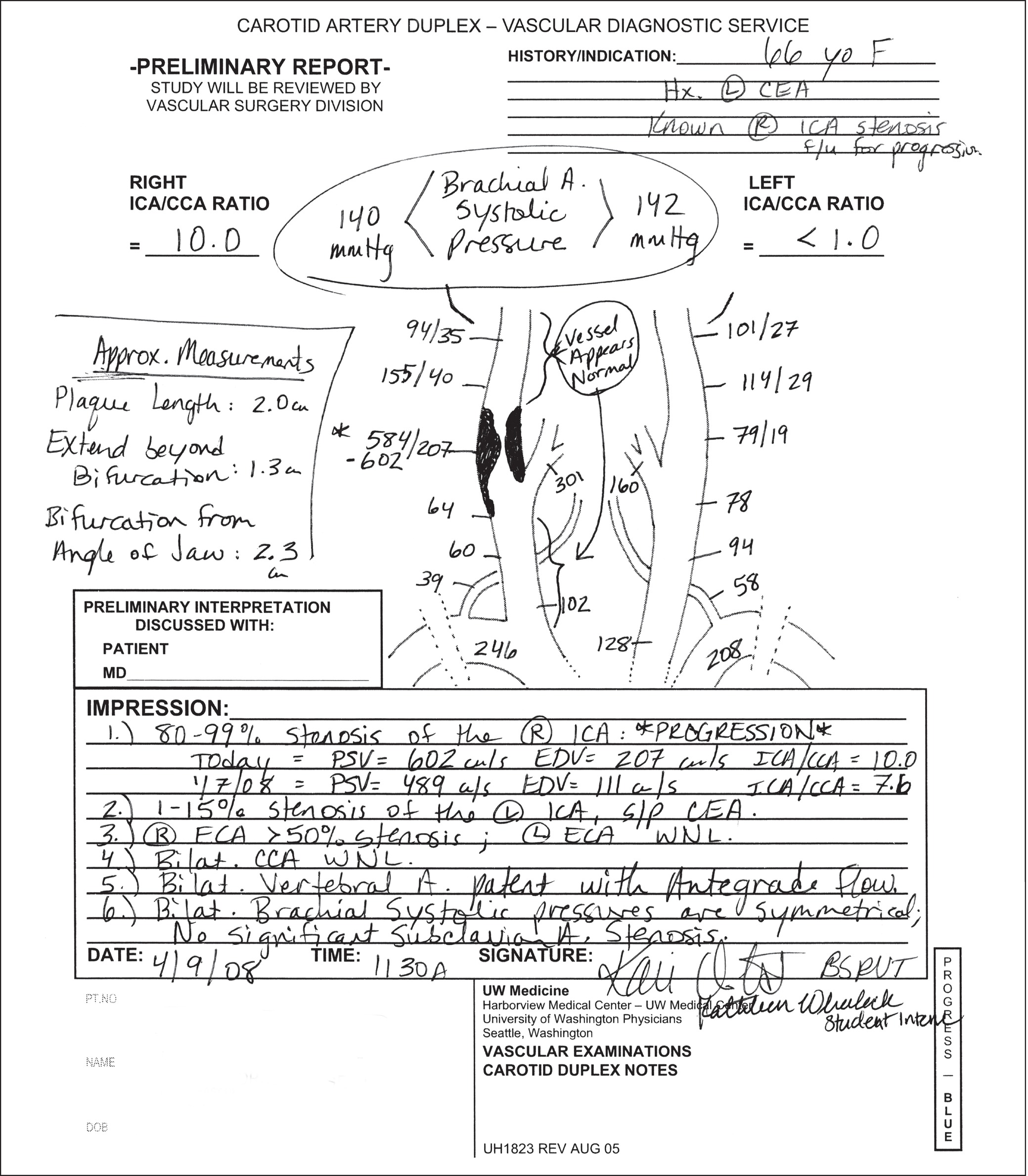

In many vascular laboratories, preliminary reports are either verbal or handwritten (or both). When a report is given verbally, it is important for the technologist to make a note documenting the person who received the report and the time of contact. Handwritten preliminary reports are often in the form of a “worksheet” that is used to record data at the time the study is performed. Figures 2.1 through 2.6 are examples of worksheets that can also serve as preliminary reports. Drawings done by the examining technologist can be very helpful when there are multiple abnormalities or unusual vascular anatomy. While worksheets such as these can be useful in the clinical setting, they are not required, and some laboratories have stopped using worksheets in an effort to go “paperless.”

FIGURE 2.1. Carotid duplex worksheet and preliminary report.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree