Practical Procedures

Arterial blood sampling

An arterial blood sample is used to measure the arterial oxygen tension (PaO2), carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2), pH and bicarbonate/base excess levels, and haemoglobin (Hb) saturation (SaO2).

Familiarize yourself with the location and the use of the blood gas machine. Arterial blood is obtained either by percutaneous needle puncture or from an indwelling arterial line.

Radial artery

The radial artery is more accessible and more comfortable for the patient; it is best palpated between the bony head of the distal radius and the tendon of the flexor carpi radialis with the wrist dorsiflexed. The Allen test is used to identify impaired collateral circulation in the hand (a contraindication to radial artery puncture): the patient’s hand is held high, with the fist clenched and both the radial and ulnar arteries compressed. The hand is lowered, the fist is opened, and the pressure from the ulnar artery is released. Colour should return to the hand within 5 seconds.

Brachial artery

The brachial artery is best palpated medial to the biceps tendon in the antecubital fossa, with the arm extended and the palm facing up. The needle is inserted just above the elbow crease.

Femoral artery

The femoral artery is best palpated just below the midpoint of the inguinal ligament, with the leg extended. The needle is inserted below the inguinal ligament at a 90 degree angle.

The chosen puncture site should be cleaned. Local anaesthetic should be infiltrated (not into the artery). Use one hand to palpate the artery and the other hand to advance the heparin-coated syringe and needle (22-25 gauge) at a 60-90 degree angle to the skin, with gentle aspiration. A flush of bright red blood indicates successful puncture. Remove about 2-3 mL of blood, withdraw the needle, and ask an assistant to apply pressure to the puncture site for 5-15 minutes. Air bubbles should be removed. The sample is placed on ice and analysed within 15 minutes (to reduce oxygen consumption by white blood cells (WBCs)).

Complications

These include persistent bleeding, bruising, injury to the blood vessel, and local thrombosis.

Arterial line insertion: introduction

Indications

Continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure in critically ill patients with haemodynamic instability.

Repeated arterial blood sampling.

Contraindications

Coagulopathy

Raynaud’s phenomenon

Thromboangiitis obliterans

Advanced atherosclerosis

End arteries such as the brachial artery should be avoided.

Initial measures

Locate a palpable artery (e.g. radial or femoral).

Assess ulnar blood flow using the Allen test, before inserting a radial line (see Arterial blood sampling, p. 784).

Arterial blood sampling, p. 784).

Position the hand in moderate dorsiflexion with the palm facing up (to bring the artery closer to the skin).

The site should be cleaned with a sterile preparation solution and draped appropriately.

Use sterile gloves.

Use local anaesthetic (1% lidocaine) in a conscious patient.

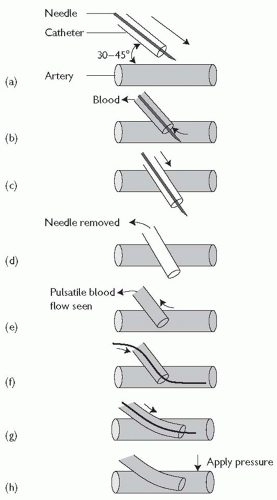

Arterial line insertion: over-the-wire technique (see Fig. 18.1)

Palpate the artery with the non-dominant hand (1-2 cm from the wrist between the bony head of the distal radius and the flexor carpi radialis tendon).

The catheter and needle are advanced towards the artery at a 30-45° angle (Fig. 18.1(a)) until blood return is seen (Fig. 18.1(b)).

The catheter and needle are then advanced through the vessel a few millimetres further (Fig. 18.1(c)).

The needle is removed (Fig. 18.1(d)).

The catheter is slowly withdrawn until pulsatile blood flow is seen (Fig. 18.1(e)).

When pulsatile blood flow is seen, the wire is advanced into the vessel (Fig. 18.1(f)).

The catheter is advanced further into the vessel over the wire (Fig. 18.1(g)).

While placing pressure over the artery, the wire is removed (Fig. 18.1 (h)) and the catheter is connected to a transduction system.

Secure the catheter in place using suture or tape.

Check perfusion to the hand after insertion of the arterial line and at frequent intervals.

The line should be removed if there are any signs of vascular compromise, or as early as possible after it is no longer needed.

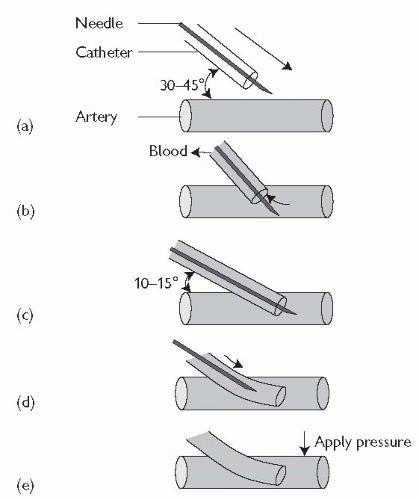

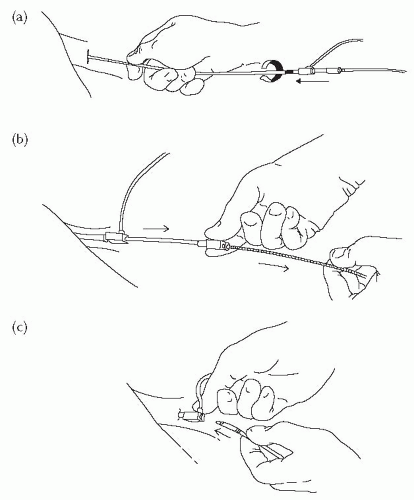

Arterial line insertion: over-the-needle technique (see Fig. 18.2)

Locate and palpate the artery with the non-dominant hand (1-2 cm from the wrist between the bony head of the distal radius and the flexor carpi radialis tendon).

The catheter and needle are advanced towards the artery at a 30-45° angle (Fig. 18.2(a)) until blood return is seen (Fig. 18.2(b)).

The catheter and needle are then advanced slightly further and the catheter/needle angle is lowered to 10-15° (Fig. 18.2(c)).

The catheter is advanced over the needle into the vessel (Fig. 18.2(d)).

Proximal pressure is applied to the artery, the needle is removed (Fig. 18.2(e)), and the catheter is connected to the transduction system.

Secure the catheter in place using suture or tape.

Check perfusion to the hand after insertion of the arterial line and at frequent intervals.

Complications

Local and systemic infection.

Bleeding, haematoma, bruising.

Vascular complications: blood vessel injury, pseudoaneurysm, thromboembolism, and vasospasm.

Arterial spasm may occur after multiple unsuccessful attempts at arterial catheterization. If this occurs, use an alternative site.

There may be difficulty in passing a wire or catheter despite the return of pulsatile blood. Adjustment of the angle, withdrawal of the needle, or a slight advance, may be helpful.

Central line insertion

You will need the following

Sterile dressing pack and gloves.

10 mL and 5 mL syringe with green (21G) and orange (25G) needles

Local anaesthetic (e.g. 2% lidocaine).

Central line (e.g. 16G long Abbocath® or Seldinger catheter)

Saline flush.

Silk suture and needle.

No. 11 scalpel blade.

Sterile occlusive dressing (e.g. Tegaderm®).

Risks

Arterial puncture (remove and apply local pressure).

Pneumothorax (insert chest drain or aspirate if required).

Haemothorax.

Chylothorax (mainly left subclavian lines).

Infection (local, septicaemia, bacterial endocarditis).

Brachial plexus or cervical root damage (over-enthusiastic infiltration with local anaesthetic).

Arrhythmias.

General procedure

The basic technique is the same whatever vein is cannulated.

Lie the patient supine (± head-down tilt).

Turn the patient’s head away from the side you wish to cannulate.

Clean the skin with iodine or chlorhexidine: from the angle of the jaw to the clavicle for internal jugular vein (IJV) cannulation, and from the midline to the axilla for the subclavian approach.

Use the drapes to isolate the sterile field.

Flush the lumen of the central line with saline.

Identify your landmarks (see Central line insertion, p. 790 and Internal jugular vein cannulation, p. 792).

Central line insertion, p. 790 and Internal jugular vein cannulation, p. 792).

Infiltrate the skin and subcutaneous tissue with local anaesthetic.

Have the introducer needle and Seldinger guide wire within easy reach so that you can reach them with one hand without having to release your other hand. Your fingers may be distorting the anatomy slightly, making access to the vein easier, and if released it may prove difficult to relocate the vein.

With the introducer needle in the vein, check that you can aspirate blood freely. Use the hand that was on the pulse to immobilize the needle relative to the skin and mandible or clavicle.

Remove the syringe and pass the guide wire into the vein; it should pass freely. If there is resistance, remove the wire, check that the needle is still within the lumen, and try again.

Remove the needle, leaving the wire within the vein and use a sterile swab to maintain gentle pressure over the site of venepuncture to prevent excessive bleeding.

With a No. 11 blade, make a nick in the skin where the wire enters, to facilitate dilatation of the subcutaneous tissues. Pass the dilator over the wire and remove, leaving the wire in situ.

Pass the central line over the wire into the vein. Remove the guide wire, flush the lumen with fresh saline, and close off to air.

Suture the line in place and cover the skin penetration site with a sterile occlusive dressing.

Measuring the central venous pressure (CVP): tips and pitfalls

When asked to see a patient with an abnormal CVP reading at night on the wards, it is a good habit to always re-check the zero and the reading yourself.

Always do measurements with the mid-axillary point as the zero reference. Sitting the patient up will drop the central filling pressure (pooling in the veins).

Fill the manometer line, being careful not to soak the cotton wall stopping. If this gets wet, it limits the free-fall of saline or dextrose in the manometer line.

Look at the rate and character of the venous pressure. It should fall to its value quickly and swing with respiration.

If it fails to fall quickly, consider whether the line is open (i.e. saline running in), blocked with blood clot, positional (up against the vessel wall—ask the patient to take some deep breaths), arterial blood (blood tracks back up the line). Raise the whole dripstand (if you are strong), and make sure that the level falls. If it falls when the whole stand is elevated, it may be that the CVP is very high.

It is easier, and safer, to cannulate a central vein with the patient supine or head down. There is an increased risk of air embolus if the patient is semi-recumbent.

Internal jugular vein cannulation

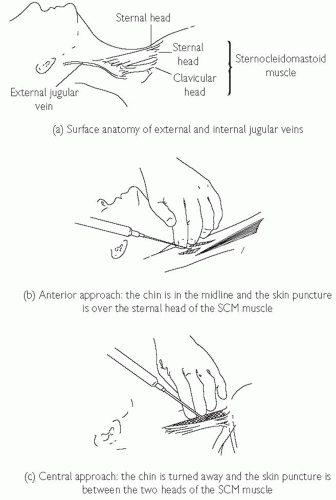

The IJV runs just posterolateral to the carotid artery within the carotid sheath and lies medial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) in the upper part of the neck, between the two heads of the SCM in its medial portion, and enters the subclavian vein near the medial border of the anterior scalene muscle (see Fig. 18.3). There are three basic approaches to IJV cannulation: medial to SCM, between the two heads of the SCM, or lateral to the SCM. The approach used varies and depends on the experience of the operator and the institution.

Locate the carotid artery between the sternal and clavicular heads of the SCM at the level of the thyroid cartilage; the IJV lies just lateral and parallel to it.

Keeping the fingers of one hand on the carotid pulsation, infiltrate the skin with local anaesthetic thoroughly, aiming just lateral to this and ensuring that you are not in a vein.

Ideally, first locate the vein with a blue or green needle. Advance the needle at 45° to the skin, with gentle negative suction on the syringe, aiming for the ipsilateral nipple, lateral to the pulse.

If you fail to find the vein, withdraw the needle slowly, maintaining negative suction on the syringe (you may have inadvertently transfixed the vein). Aim slightly more medially and try again.

Once you have identified the position of the vein, change to the syringe with the introducer needle, cannulate the vein, and pass the guide wire into the vein (see Pulmonary artery catheterization, pp. 800-5).

Pulmonary artery catheterization, pp. 800-5).

Tips and pitfalls

Venous blood is dark, and arterial blood is pulsatile and bright red!

Once you locate the vein, change to the syringe with the introducer needle, taking care not to release your fingers from the pulse; they may be distorting the anatomy slightly, making access to the vein easier, and if released it may prove difficult to relocate the vein.

The guide wire should pass freely down the needle and into the vein. With the left IJV approach, there are several acute bends that need to be negotiated. If the guide wire keeps passing down the wrong route, ask your assistant to hold the patient’s arms out at 90° to the bed, or even above the patient’s head, to coax the guide wire down the correct path.

For patients who are intubated or require respiratory support, it may be difficult to access the head of the bed. The anterior approach may be easier (see Fig. 18.3) and may be done from the side of the bed (the left side of the bed for right-handed operators, using the left hand to locate the pulse and the right to cannulate the vein).

The IJV may also be readily cannulated with a long Abbocath®. No guide wire is necessary, but, as a result, misplacement is more common than with the Seldinger technique.

When using an Abbocath®, on cannulating the vein, remember to advance the sheath and needle a few mm to allow the tip of the plastic sheath (˜1 mm behind the tip of the bevelled needle) to enter the vein. Holding the needle stationary, advance the sheath over it into the vein.

Arrange for a chest X-ray (CXR) to confirm the position of the line.

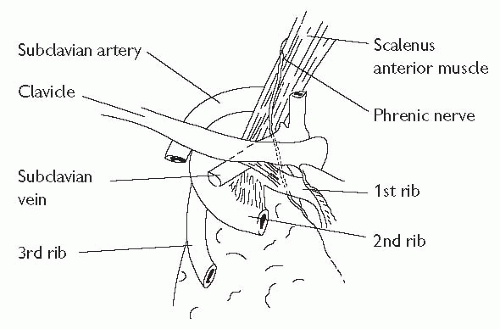

Subclavian vein cannulation

The axillary vein becomes the subclavian vein (SCV) at the lateral border of the 1st rib and extends for 3-4 cm just deep to the clavicle. It is joined by the ipsilateral IJV to become the brachiocephalic vein behind the sternoclavicular joint (see Fig. 18.4). The subclavian artery and brachial plexus lie posteriorly, separated from the vein by the scalenus anterior muscle. The phrenic nerve and the internal mammary artery lie behind the medial portion of the SCV and, on the left, lies the thoracic duct.

Select the point 1 cm below the junction of the medial third and middle third of the clavicle. If possible, place a bag of saline between the scapulae to extend the spine.

Clean the skin with iodine or chlorhexidine.

Infiltrate the skin and subcutaneous tissue and periosteum of the inferior border of the clavicle with local anaesthetic up to the hilt of the green (21G) needle, ensuring that it is not in a vein.

Insert the introducer needle with a 10 mL syringe, guiding gently under the clavicle. It is safest to initially hit the clavicle, and ‘walk’ the needle under it until the inferior border is just cleared. In this way you keep the needle as superficial to the dome of the pleura as possible. Once it has just skimmed underneath the clavicle, advance it slowly towards the contralateral sternoclavicular joint, aspirating as you advance. Using this technique, the risk of pneumothorax is small, and success is high.

Once the venous blood is obtained, rotate the bevel of the needle towards the heart. This encourages the guide wire to pass down the brachiocephalic vein rather than up the IJV.

The wire should pass easily into the vein. If there is difficulty, try advancing during the inspiratory and expiratory phases of the respiratory cycle.

Once the guide wire is in place, remove the introducer needle, and pass the dilator over the wire. When removing the dilator, note the direction that it faces; it should be slightly curved downwards. If it is slightly curved upwards, then it is likely that the wire has passed up into the IJV. The wire may be manipulated into the brachiocephalic vein under fluoroscopic control but, if this is not available, it is safer to remove the wire and start again.

After removing the dilator, pass the central venous catheter over the guide wire, remove the guide wire, and secure as above.

A CXR is mandatory after subclavian line insertion, to exclude a pneumothorax and to confirm satisfactory placement of the line, especially if fluoroscopy was not employed.

Ultrasound-guided central venous catheterization (1)

Traditional central venous catheterization methods rely on anatomical landmarks to predict vein position. However, the relationship between such landmarks and vein position varies significantly in ‘normal’ individuals. Failure and complication rates using landmark methods are significant, and therefore serious complications may occur. Recent advances in portable ultrasound equipment have now made it possible to insert central venous catheters under two-dimensional (2D) ultrasound guidance.

Advantages of this technique include:

identification of the actual and relative vein position

identification of anatomical variations

confirmation of target vein patency.

Guidelines from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (September 2002) state: ‘Two-dimensional imaging ultrasound guidance is recommended as the preferred method for insertion of central venous catheters into the internal-jugular vein (IJV) in adults and children in elective situations’. However, training and equipment availability render such recommendations effectively useless in the UK at present.

Equipment/personnel needed

Standard Seldinger-type kit or whatever is locally available.

An assistant is essential.

Ultrasound equipment:

screen: displays 2D ultrasound image of anatomical structures.

sheaths: dedicated, sterile sheaths of PVC or latex, long enough to cover the probe and connecting cable (a rubber band secures the sheath to the probe).

probe: transducer which emits and receives ultrasound information to be processed for display; marked with an arrow or notch for orientation.

power: battery or mains.

sterile gel: transmits ultrasound and provides good interface between patient and probe.

Preparation

Perform a preliminary non-sterile scan to access each IJV for patency and size.

Patient

Sterile precautions should be taken with patient’s head turned slightly away from the cannulation site. Head-down tilt (if tolerated) or leg elevation should be used to increase the filling and size of the IJV. Ensure adequate drapes to maintain a sterile field.

Excessive head rotation or extension may decrease the diameter of the vein.

Ultrasound equipment

Ensure that the display can be seen.

The sheath is opened (operator) and gel squirted in (assistant).

A generous amount of gel ensures good contact and air-free coupling between the probe tip and sheath. Too little may compromise image quality.

The probe and connecting cable are lowered into the sheath (assistant), which is then unrolled along them (operator).

A rubber band secures the sheath to the probe.

The sheath over the probe tip is smoothed out (wrinkles will degrade image quality).

Apply liberal amounts of gel to the sheathed probe tip for good ultrasound transmission and increased patient comfort during movement.

Ultrasound-guided central venous catheterization (2)

Scanning

The most popular scanning orientation for IJV central catheter placement is the transverse plane:

apply the probe tip gently to the neck lateral to the carotid pulse at the cricoid level or in the sternomastoid-clavicular triangle.

keep the probe perpendicular at all times, with the tip flat against the skin.

orientate the probe so that movement to the left ensures that the display looks to the left (and vice versa). Probes are usually marked to help orientation. By convention, the mark should be to the patient’s right (transverse plane) or to the head (longitudinal scan). The marked side appears on the screen as a bright dot.

if the vessels are not immediately visible, keep the probe perpendicular and gently glide medially or laterally until they are found.

When moving the probe, watch the screen—not your hands.

After identification of the internal jugular vein

Position the probe so that the IJV is shown at the display’s horizontal midpoint.

Keep the probe immobile.

Direct the needle (bevel towards probe) caudally under the marked midpoint of the probe tip at approximately 60° to the skin.

The needle bevel faces the probe to help direct the guide wire down the IJV later.

Advance the needle towards the IJV.

Needle passage causes a ‘wavefront’ of tissue compression. This is used to judge the progress of the needle and position. Absence of visible tissue reaction indicates incorrect needle placement. Just before vessel entry, ‘tenting’ of the vein is usually observed.

One of the most difficult aspects to learn initially, is the steep needle angulation required, but this ensures that the needle enters the IJV in the ultrasound (US) beam and takes the shortest and most direct route through the tissues.

Needle pressure may oppose the vein walls, resulting in vein transfixion. Slow withdrawal of the needle with continuous aspiration can help result in lumen access.

Pass the guide wire into the jugular vein in the usual fashion.

Re-angling the needle from 60° to a shallower angle, e.g. 45°, may help guide-wire feeding. Scanning the vein in the longitudinal plane may demonstrate the catheter in the vessel but after securing and dressing the central venous catheter (CVC), an X-ray should still be obtained to confirm the CVC position, and exclude pneumothorax.

The most common error in measurement of CVP, particularly in CVP lines that have been in place for some time, is due to partial or complete line blockade. With the manometer connected, ensure that the line is

free flowing; minor blockages can be removed by squeezing the rubber bung, with the proximal line being obliterated by acute angulation (i.e. bend the tube proximally). Measure the CVP at the mid-axillary line with the patient supine. CVP falls with upright or semi-upright recumbency, regardless of the reference point. If the CVP is high, lift the stand that holds the manometer so that the apparent CVP falls by 10 cm or so, and replace the CVP stand to ground level. If the saline or manometer reading rises to the same level, then the CVP reading is accurate. In other words, one ensures that the CVP manometer level both falls to and rises to the same level.

free flowing; minor blockages can be removed by squeezing the rubber bung, with the proximal line being obliterated by acute angulation (i.e. bend the tube proximally). Measure the CVP at the mid-axillary line with the patient supine. CVP falls with upright or semi-upright recumbency, regardless of the reference point. If the CVP is high, lift the stand that holds the manometer so that the apparent CVP falls by 10 cm or so, and replace the CVP stand to ground level. If the saline or manometer reading rises to the same level, then the CVP reading is accurate. In other words, one ensures that the CVP manometer level both falls to and rises to the same level.

Pulmonary artery catheterization (1)

Indications

Pulmonary artery (PA) catheters (Swan-Ganz catheters) allow direct measurement of a number of haemodynamic parameters that aid clinical decision making in critically ill patients (evaluate right and left ventricular function, guide treatment, and provide prognostic information). The catheter itself has no therapeutic benefit and there have been a number of studies showing increased mortality (and morbidity) with their use. Consider inserting a PA catheter in any critically ill patient, after discussion with an experienced physician about whether the measurements will influence decisions on therapy (and not just to reassure yourself). Careful and frequent clinical assessment of the patient should always accompany measurements, and PA catheterization should not delay treatment of the patient.

General indications (not a comprehensive list) include:

management of complicated myocardial infarction (MI).

assessment and management of shock.

assessment and management of respiratory distress (cardiogenic vs. non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema).

evaluation of the effects of treatment in unstable patients (e.g. inotropes, vasodilators, mechanical ventilation, etc.).

delivering therapy (e.g. thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism, prostacyclin for pulmonary hypertension, etc.).

assessment of fluid requirements in critically ill patients.

Equipment required

Full resuscitation facilities should be available and the patient’s electrocardiogram (ECG) should be continuously monitored.

Bag of heparinized saline for flushing the catheter and transducer set for pressure monitoring. (Check that your assistant is experienced in setting up the transducer system BEFORE you start.).

8F introducer kit (pre-packaged kits contain the introducer sheath and all the equipment required for central venous cannulation).

PA catheter: commonly a triple-lumen catheter, that allows simultaneous measurement of right atrial (RA) pressure (proximal port) and PA pressure (distal port) and incorporates a thermistor for measurement of cardiac output by thermodilution. Check your catheter before you start.

Fluoroscopy is preferable, though not essential.

General technique (see Fig. 18.5)

Do not attempt this without supervision if you are inexperienced.

Observe strict aseptic technique using sterile drapes, etc.

Insert the introducer sheath (at least 8F in size) into either the internal jugular or subclavian vein in the standard way. Flush the sheath with saline and secure to the skin with sutures.

Do not attach the plastic sterile expandable sheath to the introducer yet but keep it sterile for use later once the catheter is in position (the catheter is easier to manipulate without the plastic covering).

Flush all the lumens of the PA catheter and attach the distal lumen to the pressure transducer. Check the transducer is zeroed (conventionally to the mid-axillary point). Check the integrity of the balloon by inflating it with the syringe provided (1-2 mL air), and then deflate the balloon.

Fig. 18.5 Pulmonary artery catheterization. (a) The sheath and dilator are advanced into the vein over the guide wire. A twisting motion makes insertion easier. (b) The guide wire and dilator are then removed. The sheath has a haemostatic valve at the end preventing leakage of blood. (c) The PA catheter is then inserted through the introducer sheath into the vein. |

Pulmonary artery catheterization (2)

Insertion technique

Flush all the lumens of the PA catheter and attach the distal lumen to the pressure transducer. Check the transducer is zeroed (conventionally to the mid-axillary point). Check the integrity of the balloon by inflating it with the syringe provided and then deflate the balloon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree