Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is associated with increased risk of multiple medical problems including myocardial infarction. However, a direct link between PTSD and atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD) has not been made. Coronary artery calcium (CAC) score is an excellent method to detect atherosclerosis. This study investigated the association of PTSD to atherosclerotic CAD and mortality. Six hundred thirty-seven veterans without known CAD (61 ± 9 years of age, 12.2% women) underwent CAC scanning for clinical indications and their psychological health status (PTSD vs non-PTSD) was evaluated. In subjects with PTSD, CAC was more prevalent than in the non-PTSD cohort (76.1% vs 59%, p = 0.001) and their CAC scores were significantly higher in each Framingham risk score category compared to the non-PTSD group. Multivariable generalized linear regression analysis identified PTSD as an independent predictor of presence and extent of atherosclerotic CAD (p <0.01). During a mean follow-up of 42 months, the death rate was higher in the PTSD compared to the non-PTSD group (15, 17.1%, vs 57, 10.4%, p = 0.003). Multivariable survival regression analyses revealed a significant linkage between PTSD and mortality and between CAC and mortality. After adjustment for risk factors, relative risk (RR) of death was 1.48 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03 to 2.91, p = 0.01) in subjects with PTSD and CAC score >0 compared to subjects without PTSD and CAC score equal to 0. With a CAC score equal to 0, risk of death was not different between subjects with and without PTSD (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.67 to 6.82, p = 0.4). Risk of death in each CAC category was higher in subjects with PTSD compared to matched subjects without PTSD (RRs 1.23 for CAC scores 1 to 100, 1.51 for CAC scores 101 to 400, and 1.81 for CAC scores ≥400, p <0.05 for all comparisons). In conclusion, PTSD is associated with presence and severity of coronary atherosclerosis and predicts mortality independent of age, gender, and conventional risk factors.

Psychological stress and mental disorders have long been linked to cardiovascular disorders. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a growing and well-recognized psychological disorder stemming from previous significant stressful conditions. Lifetime prevalence of combat PTSD is 5% to 20% in the United States and is even more prevalent in military personnel serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. In addition to debilitating declines in physical and psychological health, PTSD is associated with increased rates of multiple medical disorders and many surrogate and biomarker abnormalities. Although many studies have linked PTSD to cardiovascular diseases and myocardial infarction (MI), a conclusive link between PTSD and atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD) has not been made. The Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the nation, provides integrated comprehensive physical and psychological assessment of veterans in the primary care setting. This provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the relation between psychological disorders such as PTSD and CAD. Coronary artery calcium (CAC) is an accurate marker of the presence and overall atherosclerotic burden and correlates with oxidative stress, vascular dysfunction, plaque burden, presence of obstructive CAD, and increased cardiovascular events. The present study investigated the (1) association of PTSD to coronary artery atherosclerosis as measured by CAC score and (2) relation of PTSD to coronary atherosclerosis and mortality in veterans without known CAD.

Methods

The study population consisted of 637 consecutive veterans without known CAD (61 ± 9 years of age, 12.2% women) who underwent CAC scanning for clinical indications. Subjects with established CAD, schizophrenia, and major psychological disorders were excluded.

CAC was detected using a Siemens Definition dual-source 64-slice scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany). The dual-source computed tomographic protocol has been described previously and validated by comparison to electron beam computed tomography. Coronary arteries were imaged with 30 to 40 contiguous 3-mm slices during mid-diastole using electrocardiographic triggering during a 15-second breath-hold. CAC was considered present in a coronary artery when a density >130 HU was detected in ≥3 contiguous pixels (>1 mm 2 ) overlying the coronary artery and then quantified.

Conventional cardiovascular risk factors were measured using the Framingham Risk Score. Medical information was obtained from electronic medical records. Subjects receiving antihypertensive drugs or with systolic or diastolic blood pressures ≥140 and 90 mm Hg were considered hypertensive. Subjects were deemed dyslipidemic if they were receiving lipid-lowering therapy. Subjects were considered diabetic if they were being treated for diabetes. Risk factors were determined and Framingham Risk Score was calculated to assess the risk of developing coronary disease events (MI or coronary heart disease death) over the next 10 years. Mortality verified by Social Security Death Index was obtained from electronic medical records.

The PTSD Checklist–Military and Clinician Administered PTSD Scale were administered. The PTSD Checklist–Military is a 17-item questionnaire adapted from PTSD criteria B to D from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition , which inquires about the 3 symptom clusters of PTSD: 5 re-experiencing symptoms, 7 numbing/avoidance symptoms, and 5 hyperarousal symptoms. The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale assesses the frequency and intensity of PTSD symptoms during the previous month. Those patients with positive Clinician Administered PTSD Scale and PTSD Checklist–Military scores were classified as having PTSD. PTSD diagnosis was collected from Veteran Health Administration electronic medical records.

All continuous data are presented as mean ± SD, and all categorical data are reported as percentage or absolute number. Chi-square and t tests were used to assess differences between groups. Multivariable generalized linear models were used to assess the association of PTSD with presence and severity of coronary atherosclerosis. Multivariable Cox regression survival analysis was employed to assess the inter-relation of PTSD and CAC with mortality risk before and after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors. Relative risk (RR) of death and confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a bootstrapping technique. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed for categories of CAC with and without PTSD and compared with log-rank test. Independent predictors of mortality were determined using Cox regression survival analysis using a bootstrapping technique. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, available at: http://www.sas.com ) and PASW 18 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, available at: http://www.spss.com ). This study was approved by the institutional review board committee of the Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System (Los Angeles, California).

Results

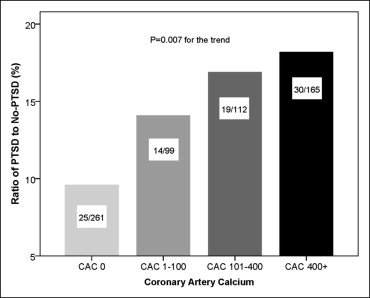

Demographic and conventional risk factors in subjects with and without PTSD are presented in Table 1 . There were no significant differences between veterans with and without PTSD in age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, family history of premature CAD, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, triglyceride, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Prevalence of hypercholesterolemia, male gender, and current smoking was higher in subjects with PTSD. CAC was more prevalent in the PTSD group compared to the non-PTSD group (76.1% vs 59%, p = 0.001). Similarly, prevalence ratio of PTSD increased with severity of CAC from <10% in CAC score 0 to 18.2% in CAC score ≥400 ( Figure 1 ) and an increase in Framingham Risk Score ( Figure 2 ). CAC was significantly greater in each Framingham Risk Score category in the PTSD cohort compared to subjects without PTSD ( Figure 2 ).

| Variable | No PTSD | PTSD | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 549) | (n = 88) | ||

| Age (years) | 58 ± 10 | 59 ± 9 | 0.3 |

| Men | 84% | 98% | 0.001 |

| Hypertension ⁎ | 54% | 63% | 0.1 |

| Hypercholesterolemia † | 47% | 63% | 0.006 |

| Diabetes mellitus ‡ | 25% | 29% | 0.4 |

| Current smoker | 30% | 42% | 0.03 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 29.3 ± 6.2 | 31.0 ± 5.9 | 0.02 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.03 ± 0.22 | 1.05 ± 0.24 | 0.3 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 128 ± 14 | 127 ± 14 | 0.7 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 77 ± 8 | 77 ± 9 | 0.9 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 174 ± 46 | 163 ± 45 | 0.04 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (mg/dl) | 104 ± 34 | 100 ± 37 | 0.3 |

| High-density lipoprotein (mg/dl) | 44 ± 17 | 38 ± 13 | 0.005 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 133 ± 69 | 141 ± 76 | 0.3 |

| Framingham Risk Score | 12.1 ± 8.1 | 14.1 ± 6.7 | 0.02 |

| Coronary artery calcium score | 332 ± 336 | 448 ± 472 | 0.0001 |

| Follow-up (months) | 43 ± 12 | 39 ± 15 | 0.04 |

| Mortality | 10.4% | 17.1% | 0.003 |

⁎ Self-reported diagnosis of hypertension, prescribed medication for hypertension, or current systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg diastolic (>130/80 mm Hg if diabetic).

† Self-reported diagnosis of high cholesterol, prescribed medication for high cholesterol, or current total cholesterol level >200 mg/dl.

‡ Self-reported diagnosis of diabetes (type 1 or 2) or prescribed medication for diabetes.

Multivariable generalized linear regression analysis identified PTSD as an independent predictor of presence and extent of atherosclerotic CAD. After adjustment for risk factors, RR of presence of CAC was 1.59 in the PTSD compared to the non-PTSD groups. Similarly, mean CAC was 86 HU higher in subjects with PTSD compared to subjects with a similar profile without PTSD ( Table 2 ).

| Model | Presence of CAC ⁎ | Severity of CAC † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Beta (95% CI) | p Value | |

| I | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 2.17 (1.16–3.95) | 0.001 | 116 (78–262) | 0.001 |

| II ‡ | ||||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1.59 (1.20–2.91) | 0.01 | 86 (37–137) | 0.008 |

⁎ Logistic regression analysis.

† Generalized linear regression analysis.

‡ Covariates were age, gender, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, family history of coronary heart disease, and smoking status.

During a mean follow-up of 42 months, there were 72 (11.3%) deaths in the entire population. The death rate was higher in the PTSD compared to the non-PTSD group (15, 17.1%, vs 57, 10.4%, p = 0.003). After adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors, CAC and PTSD were independent predictors of mortality, in which the risk of death increased 2.28-fold with presence of PTSD ( Table 3 ). Furthermore, multivariable survival regression analyses showed a significant linkage of PTSD and CAC with increased RR of death independent of risk factors ( Figure 3 and Table 4 ). The RR of death was 1.48 (95% CI 1.03 to 2.91, p = 0.01) in subjects with PTSD and CAC score >0 compared to those without PTSD and CAC score 0 after adjustment for risk factors.

| Model | RR of Death (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| I | ||

| Unadjusted | ||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1.82 (1.05–3.17) | 0.003 |

| Coronary artery calcium ⁎ | 12.54 (2.83–17.85) | 0.001 |

| II † | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.58 (1.37–4.65) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 2.81 (1.12–3.41) | 0.02 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1.77 (1.02–3.14) | 0.03 |

| III ‡ | ||

| Coronary artery calcium ⁎ | 10.85 (1.41–24.27) | 0.0001 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 2.28 (1.19–4.37) | 0.001 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree