Popliteal Artery Aneurysm—Open Repair

PAUL D. DIMUSTO and PETER K. HENKE

Presentation

A 65-year-old man was referred to the vascular surgery clinic for evaluation of a large abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) discovered on screening ultrasound performed by his primary care physician given his 50-pack-year smoking history. The patient also has medical history significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease with prior myocardial infarction, and he is morbidly obese. He has undergone coronary artery bypass grafting 10 years ago and coronary artery stent placement 3 years ago. He takes an aspirin, statin, and beta-blocker daily, among other medications. He has a family history of coronary artery disease, but no family history of aneurysms.

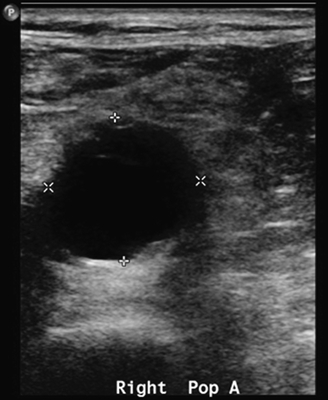

On examination in the clinic, he has a pulsatile abdominal mass and palpable femoral and pedal pulses bilaterally. As a part of his evaluation, he undergoes a duplex ultrasound scan of his bilateral femoral and popliteal arteries to survey for occult aneurysms, as well as ankle-brachial index (ABI). He is discovered to have bilateral popliteal aneurysms measuring 2.5 cm in diameter on the right (Fig. 1) and 2.2 cm on the left, with the right extending below the tibial plateau. His ABIs are 0.9 bilaterally with triphasic pedal waveforms.

FIGURE 1 Ultrasound image showing large right popliteal aneurysm.

Differential Diagnosis

Popliteal artery aneurysms (PAAs) are uncommon in the general population, with an incidence of less than 0.1%. However, in patients with AAAs, up to 14% will have femoral or popliteal aneurysms, with 10% having isolated PAA. They may present as a pulsatile mass in the popliteal fossa, but the majority are not detectable on physical exam, especially as the population becomes more obese. The differential diagnosis for a mass in the popliteal fossa includes a Baker’s cyst, lipoma, hematoma, venous thrombosis, sarcoma, or lymphoma. These are all less likely in this patient.

Discussion

A PAA is defined as a dilation of the artery that is 1.5 to 2 times the diameter of the normal artery. Thus, a diameter of 1.5 to 2 cm is considered aneurysmal in most patients. PPAs occur almost exclusively in men with an approximately 30:1 male-to-female ratio in incidence. Ninety-six percent of PAAs were found in men in a large review of the literature. This is different than AAA, which typically has a 4:1 male-to-female ratio of incidence.

The pathophysiology of PAA is not entirely clear, but is thought to be more inflammatory in nature compared to the atherosclerotic degeneration seen in AAAs. In a study of patients with known AAAs, peripheral artery disease was more common in patients with PAA than in those AAAs and no peripheral aneurysms.

In this patient, his PAAs are asymptomatic and were discovered incidentally while undergoing workup for his AAA. However, 40% to 60% of patients will present with some form of symptoms. Most will present with ischemic symptoms, ranging from claudication (25%), to rest pain, to acute critical limb ischemia (25%). Patients may also present with evidence of repeated distal embolization, commonly referred to as “blue toe syndrome,” and often have a slight decrease in perfusion and tibial occlusion. Finally, symptoms due to compression of the tibial nerve (neuropathy) or the popliteal vein (limb swelling or deep venous thrombosis) can also occur.

If a PAA is discovered de novo, the patient should undergo screening for AAA, as 38% to 62% of patients presenting with PAA will have a concomitant AAA and 15% will have a concomitant iliac aneurysm. Additionally, 35% to 48% of patients will have bilateral PAA as our patient does.

Imaging

Duplex ultrasonography, with both gray-scale imaging to detect the aneurysm size and any luminal thrombus present, as well as color Doppler flow to assess the flow above, through, and below the aneurysm, is the initial imaging study used in the workup. This is an excellent screening test as it is noninvasive and does not involve radiation or iodinated contrast. Duplex ultrasound can also be used to follow patients postrepair.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can also be used to further evaluate a patient with a suspected or diagnosed popliteal aneurysm, particularly if the patient also has an AAA and is undergoing evaluation for repair. These can help define the inflow and outflow as well as the full extent of the aneurysm and surrounding anatomy (Table1).

TABLE 1. Key Technical Steps and Potential Pitfalls

In patients who present with acute thrombosis of a PAA and acute limb ischemia, angiography with thrombolysis may be indicated as the initial imaging study. All patients being considered for PAA repair should undergo preoperative angiography, as this will help define the outflow vessels to the foot and a suitable distal target for bypass if the ABIs are abnormal. Up to 69% of patients will have 0 to 1 infrapopliteal arteries open due to embolization from the aneurysm. However, angiography should not be used as an initial evaluation of a suspected asymptomatic aneurysm, as the aneurysm may not be detected due to thrombus in the aneurysm sac.

Case Continued

The patient underwent a CTA of the abdomen, pelvis, and lower extremities to further define the anatomy of his AAA as well as his PAA. This confirmed a 6.9-cm juxtarenal AAA as well as bilateral PAA greater than 2 cm in diameter (Figs. 2 and 3). The right extended to below the knee; the left was confined to behind the knee.

FIGURE 2 Contrast CTA in sagital section showing right popliteal aneurysm.