Etiology

Clinical appearance

Size (British Medical Society)

Spontaneous

Closed pneumothorax (also called pneumothorax simplex)

Small (lung <2 cm from the chest wall)

Symptomatic

Open pneumothorax

Large (lung >2 cm from the chest wall)

Iatrogenic

Tension pneumothorax

—

Traumatic

Hemopneumothorax

—

Some types of pneumothorax—namely, tension pneumothorax, hemopneumothorax, and simultaneous bilateral pneumothorax—may be life threatening. Tension pneumothorax is dangerous because the air freely enters the pleural space, but a valve effect created by the ruptured tissue (chest wall or lung parenchyma) prevents the air from escaping the pleural cavity, resulting in increasing pressure in the pleural cavity, total collapse of the affected lung, a shift of the mediastinum toward the opposite side, and compression of the opposite healthy lung. The return of blood to the right atrium is inhibited by the intrathoracic pressure, and without intervention the patient may die of empty heart syndrome. In these cases, patients have severe dyspnea, the affected hemithorax may look overinflated, and cyanosis of the upper part of the body may be visible. These patients often require immediate intervention via a needle puncture of the pleural space (Kelly et al. 2008).

Pneumothorax is a recurrent disease, with 53–75 % of cases recurring less than 5 years after the first episode (Devenand et al. 2004).

The differential diagnosis for pneumothorax should include the following:

Myocardial infarction

Pulmonary artery embolism

Exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Pneumonia

Hydrothorax or hemothorax

There are three basic treatments for pneumothorax (Kelly 2009):

Bed rest

Chest tube drainage

Pleurectomy

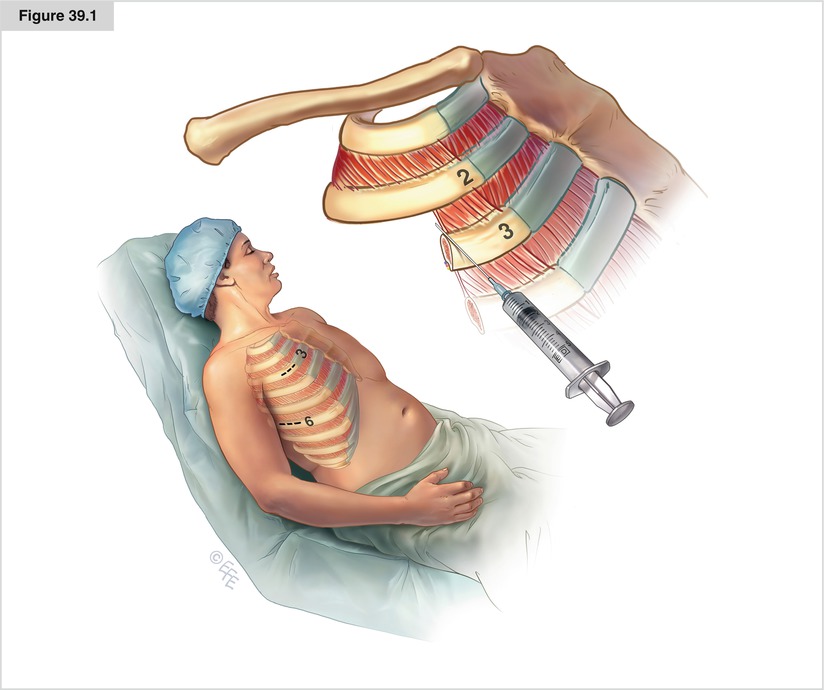

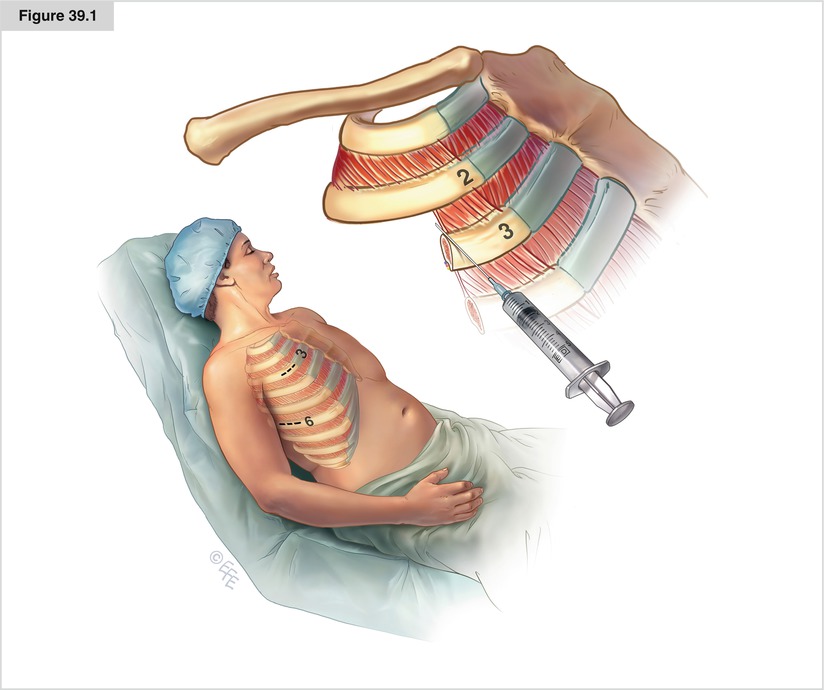

Figure 39.1

Chest tube drainage remains the most common treatment for pneumothorax. The most frequent location for drain placement is the fifth to sixth intercostal space in the midaxillary line, although some surgeons use the second intercostal space in the midclavicular line. Several types of drains are commercially available, but most surgeons prefer relatively large (24F–32F), nonirritating (silicone or soft rubber), easy-to-install drains. Before the procedure, the patient should receive an explanation of the planned treatment, as well as a sedative and analgesic. The patient is placed in a semi-sitting position (i.e. with the chest elevated ~30°). The surgeon marks the incision site; the incision should be 1–2 cm long in the second intercostal space in the midclavicular line or slightly lateral to this line (not medial because of the risk of internal mammary artery laceration). It is advisable to make the incision slightly lower on the third rib (not on the second intercostals space) to provide an oblique channel for the drain directed toward apex, which is the preferred direction for the drain. The incision site should be anesthetized by instillation of 5–8 ml of 1 % lidocaine. The needle should penetrate the pleural space on the upper rim of the third rib (not the lower rim, to avoid intercostal vessel damage) and air must be aspirated, finally confirming the diagnosis of pneumothorax

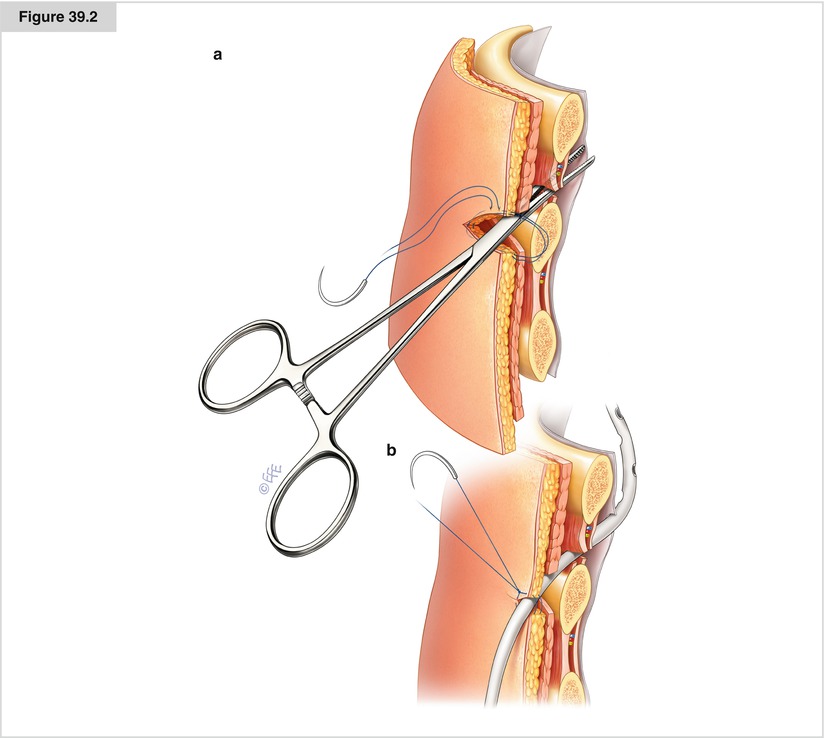

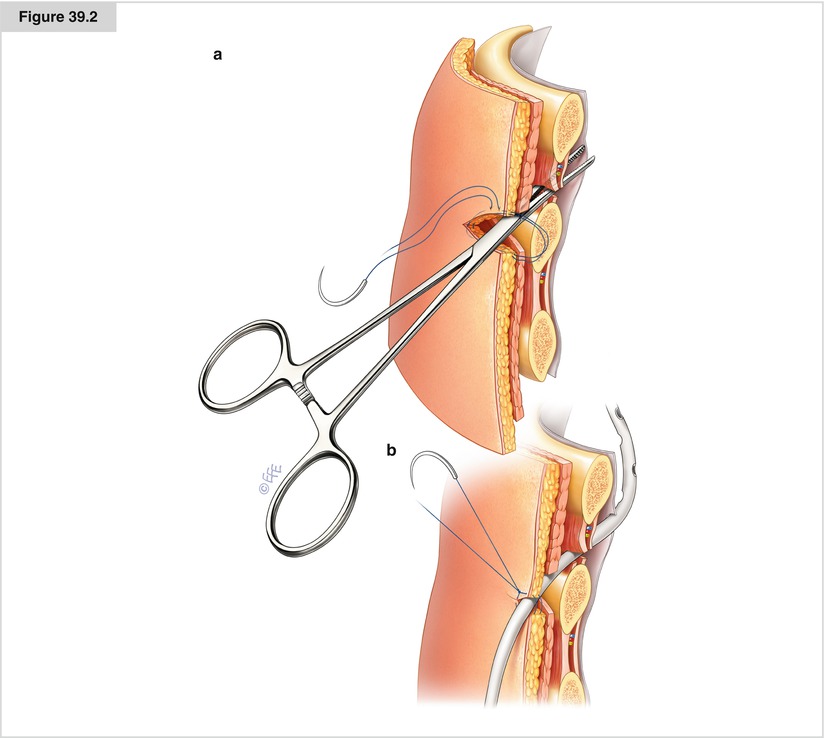

Figure 39.2

After the skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised, a suture may be placed across the incision and left untied; after the tube is removed, the suture may be tied to close the drain channel and prevent air from entering the pleura. Afterward, the surgeon should continue blunt dissection of the tissues with a clamp or trocar (delivered with some drain types) until it reaches the pleural space. A wheezing sound of evacuating air typically is heard after the pleural space is reached. The patient may experience dyspnea at this moment and become fearful of the reexpanding lung, but this usually resolves within a few minutes. (a) It is important to insert the instruments close to the upper margin of the lower rib. Inserting instrument close to the lower margin of the upper rib increases the risk of the intercostal vessels injury. (b) The chest drain should be placed upwards. It is essential to fix it to the skin by suture

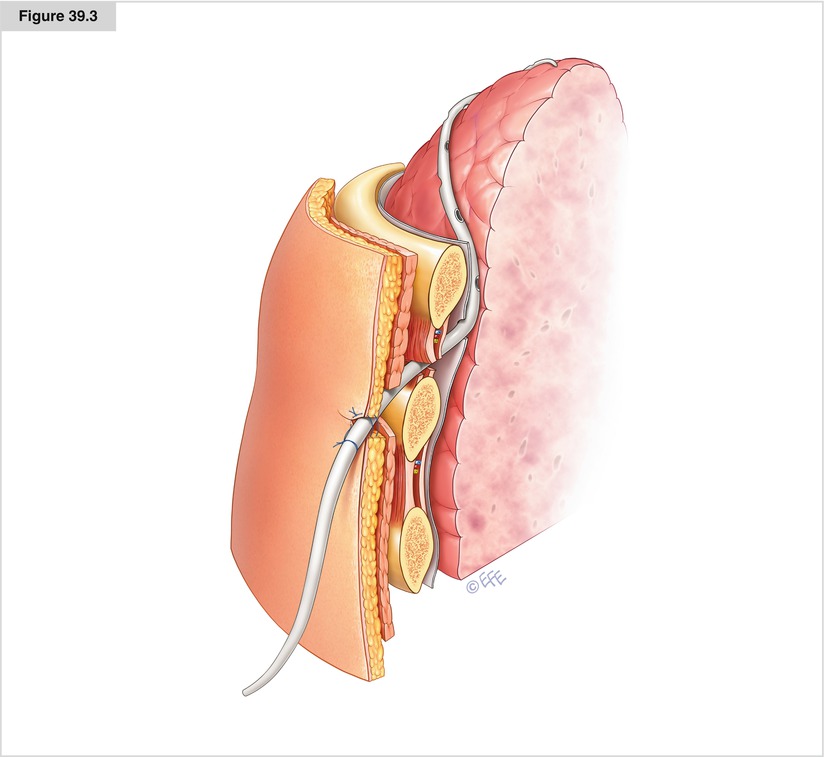

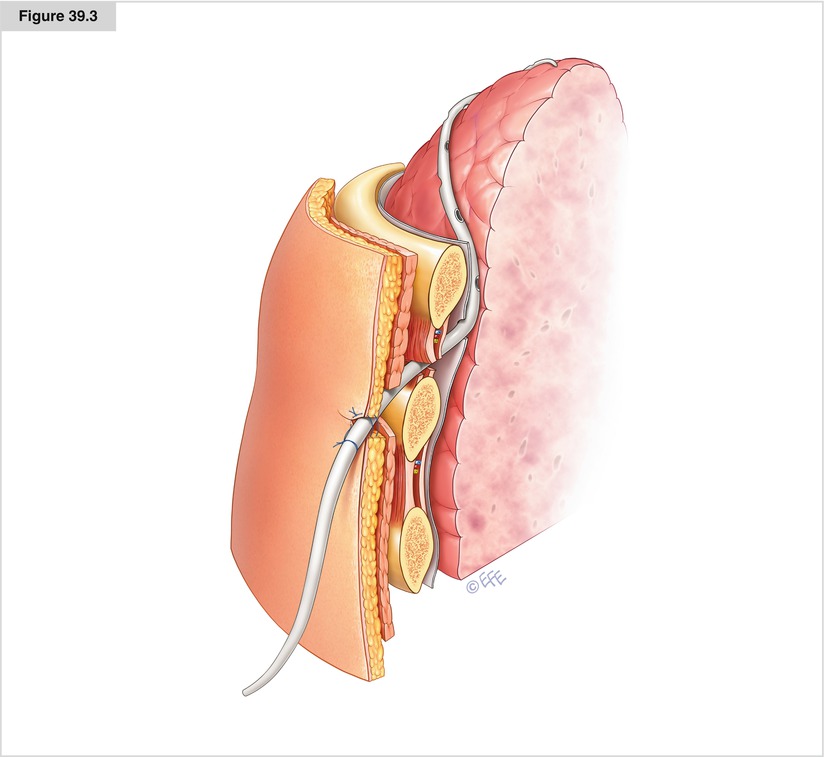

Figure 39.3

The drain is installed with the help of the long clamp or commercially available trocar. The tip of the drain must be directed toward the apex (this is easier if the drain is placed in the second intercostal space and more difficult if it passes through the sixth intercostal space). All lateral drain holes should remain in the pleural space. Sometimes it is necessary to make additional holes; however, the last one should not be closer to the chest wall than 2 cm, otherwise a false air leak might be observed. The installed drain should be connected to the drainage system; all connections must be airtight. The drain must be fixed to the skin with additional suture. There is an ongoing controversy regarding suction. Clinical practice indicates that most centers prefer active suction, but some papers suggest it seems more important after upper lobectomy than lower lobectomy. In cases of prolonged air leakage or fluid output, many centers discharge patients home with portable nonsuction devices, which are removed subsequently when air leakage stops. Although a variety of these devices are commercially available and commonly used, the thoracic surgeon should be able to construct an ad hoc drainage system in case of emergency. The simplest and easiest method is to place the chest drain into the plastic bottle used for intravenous infusions. The bottle must be placed lower than chest level (practically speaking, on the floor). Widely accepted indications for chest tube removal are as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree