Medical history

n (%)

Viral infection prior to NP

2 (6.25 %)

Tonsillar hypertrophy

2 (6.25 %)

Asthma

2 (6.25 %)

Systemic hypertension and obesity

1 (3.13 %)

Recurrent upper respiratory tract infections

1 (3.13 %)

Congenital heart disease (atrial septal defect)

1 (3.13 %)

Clinical presentation

Fever on admission

30 (93.75 %)

Tachypnea

28 (90.3 %)

Cough

24 (77.4 %)

Abdominal pain

14 (45.2 %)

Chest pain

11 (36.6 %)

Physical examination

Dullness to percussion

30 (93.8 %)

Decreased breath sounds

30 (93.8 %)

Crackles

20 (62.5 %)

Bronchial breath sounds

7 (21.9 %)

In all children, areas of lung consolidation, lucencies within consolidation areas and multiple thin–walled cavities were identified in plain chest radiograph or CT scans. In 18 and 10 children the abnormal radiographic appearance was limited to the right and left lung, respectively, while 4 patients presented with bilateral lung involvement. Pleural effusion was revealed in 31 patients and pneumothorax in 2 cases (Figs. 1 and 2).

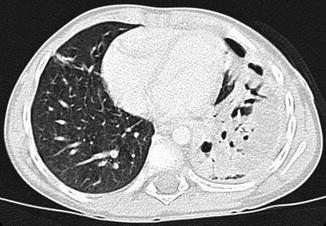

Fig. 1

Plain chest radiograph. Extensive consolidation with multiple irregular lucency areas in the middle and lower field of the left lung

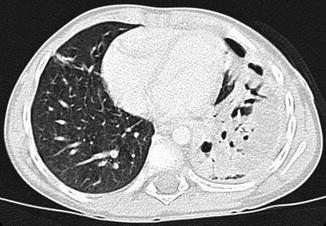

Fig. 2

Thorax computed tomography. Consolidation of the left lower lobe with multiple air filed cavities

The results of laboratory tests on admission are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Selected laboratory results in children with NP, data presented as median and IQR

Laboratory test | Result | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

CRP (mg/dl) | 18.2 (15.2–24.1) | <1.0 |

WBC (× 109/L) | 21.3 (17.7–25.2) | 4.5–13 |

Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 8.9 (8.4–9.9) | 10.9–14.2 |

Neutrophils (%) | 70 (47.4–95.6) | Age-dependent |

Platelets (× 109/L) | 818.5 (557.3–1069.3) | 150–400 |

Total serum protein (g/L) | 53.0 (49.0–58.0) | 60.0–80.0 |

Serum albumin (g/L) | 25 (23.5–27.5) | 35.0–52.0 |

There were significantly elevated acute phase reactants, with the median CRP value of 18.2 mg/dl (normal range <1 mg/dl) (IQR 15.2–24.1). The median WBC count was 21.3 × 109/L (IQR 17.7–25.2) with the polymorphonuclear cell predominance. Anemia was a common laboratory finding (median Hb concentration – 89.0 g/L, IQR 84.0–99.0 g/L). Fourteen children (43.8 %) required packed red blood cell transfusion. One child had a reduced platelet count, while the remaining children presented with thrombocytosis (median platelet count 818.5 × 109/L, (IQR 557.3–1069.3)). There was a significant percentage of children with declined total serum protein and albumin concentration (56.3 % and 84.4 %, respectively).

All children had blood culture taken on admission. In 20 children, additional blood culture results from regional hospitals were available for analysis. Microbiological studies of pleural fluid were performed in all 31 patients presenting with pleural effusion. Positive results of blood and pleural fluid analysis were found in only 6 (18.8 %) and 7 (22.5 %) children, respectively. Ultimately, blood and pleural fluid cultures enabled identification of the pathogens responsible for NP in 12 patients (1 patient had both blood and pleural fluid cultures positive). The most commonly identified species was Streptococcus pneumoniae (n = 8), followed by Staphylococcus aureus (n = 2), Streptococcus milleri (n = 1), Staphylococcus epidermidis (n = 1) and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (n = 1). All Streptococcus pneumoniae strains were susceptible to penicillin and Staphylococcus aureus strains were sensitive to methicillin (MSSA).

In all children, antibiotic therapy had been initiated before admission to the referral center. Amoxicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and cefuroxime were most commonly applied as the first line of treatment. There was no difference between the duration of pre-admission antibiotic therapy in children treated at home (median 3 days; IQR 1.75–4.25) and transferred from other hospitals (median 3 days; IQR 2–6). Due to prolonged symptoms, the initial therapy was switched to the second-line antibiotic treatment in all patients after admission to our center. The second-line therapy included cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, clindamycin, vancomycin, and carbapenems. At least a two drug-regimen was used in all patients. The median duration of antibiotic treatment was 28 days (IQR 22.5–32.5). All but one patient had NP associated complications with PPE/empyema being the most common (Table 3).

Table 3

Complications of NP

Complications of NP | n (%) |

|---|---|

Parapneumonic effusion/empyema | 31 (96.9 %) |

Bronchopulmonary fistula | 8 (25 %) |

Pneumothorax | 2 (6.25 %) |

Mortality | 0 (0 %) |

Thus, 31 children required additional local treatment (see below). The results of pleural fluid analysis are summarized in Table 4. Two children only required therapeutic thoracentesis, while in 29 (93.5 %) children the chest tube insertion and pleural drainage were necessary. Due to inadequate pleural fluid drainage one patient was subsequently treated with video- assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Intrapleural fibrynolitic treatment with urokinase was applied in 25 (78.1 %) children. The median duration of pleural drainage was 8.6 days (IQR 6–11.25, range 2–27).

Table 4

Pleural fluid characteristics; data presented as median and IQR

pH | 7.3 (7–7.5) |

Specific gravity | 1.020 (1.015–1.020) |

Protein concentration (g/L) | 38.0 (34.5–44.0) |

Lactate dehydrogenase (U/l) | 8670 (2827.5–14253.5) |

Glucose (mg/dl) | 50 (32–55) |

In two children with PPE/pleural empyema small/medium pneumothorax (pyopneumothorax) was found. Neither of them demonstrated an air leak after the chest tube insertion and both were successfully treated with pleural drainage.

Eight children (25 %) with PPE/empyema developed signs of BPF during treatment with pleural drainage. In all these patients, spontaneous healing of BPF was achieved and none of the children required surgical treatment. The median duration of air leak was 10.5 days (IQR 7–17, range 5–20). The duration of pleural drainage in children with BPF was significantly longer than in children without BPF (16 vs. 7 days, p < 0.001).

No deaths occurred in the study group. The duration of hospital stay ranged between 13 and 44 days (median 26). All children had follow-up visits 1 and 6 months after hospital discharge. At the first visit, physical examination revealed asymmetry of the chest and decreased breath sounds in the previously affected areas in 10 (31.3 %) and 14 (45.2 %) children, respectively. Chest radiographs showed residual pulmonary and pleural lesions in all patients. Five months later, none of the children revealed any abnormality on physical examination. Moreover, in all patients chest radiograph showed complete or almost complete resolution of pulmonary and pleural lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree