Pulmonary complications

Extrapulmonary complications

Suppurated pleuropulmonary complications

Immunological/infectious complications

Necrotizing pneumonia

Pneumatocele, pyopneumatocele

Pulmonary abscess

Parapneumonic pleural effusion

Pleural empyema

Mechanical complications of suppurated pneumonias: Air escaping (pneumothorax and bronchopleural fistula)

Sepsis

Toxic shock syndrome

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome

Distant focus: septic arthritis, meningitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, endocarditis

Nonsuppurated complications

Acute respiratory failure

Atelectasis

Among other complications we can consider pulmonary abscess, as cavitated pulmonary parenchyma with pus-filled material. In contrast to pyo-pneumatocele, which presents with a thin wall and with an appearance secondary to abscesses in the terminal bronchiole, pulmonary abscess is less frequent in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Pulmonary abscess presents with thick and irregular walls and usually requires prolonged antibiotic treatment. Surgery may be an option of treatment for some patients when there is a bronchopleural fistula with no response to medical therapy, the presence of persistent hemoptysis, or if the airway is compressed. Pulmonary abscess is observed in patients with massive aspiration pneumonia, chronic lung damage with bronchiectasis, pulmonary malformations, or in patients with complicated pulmonary hydatidosis. Infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus , which have become agents seen as suppurating more often than previously, produces necrotizing pneumonia, which presents as pneumonia with multiple confluent microabscesses, usually septic, that follow quickly to multiple cavitations within the consolidated parenchyma, associated with ipsilateral empyema. This suppurated complication is different from the appearance of a thin-walled air-filled image, named a pneumatocele, within the resolution of a pneumonia. In necrotizing pneumonia, it is possible to observe a bronchopleural fistula, corresponding to the communication between the pleural space and the peripheral airway, which is caused by the infected and necrotized parenchyma. A pneumatocele may cause mechanical complications because of the hyperinsufflation and parenchyma or airway compression, or because of a pleural tear, if its location is subpleural, with the formation of a secondary pneumothorax.

Epidemiology

Pneumonia is one of the most common infections in children around the world, with associated morbidity and mortality, but it is especially severe in children under 1 year old in developing countries.

WHO has estimated that every year about 156 million cases of pneumonia affect children under 5 years old, of which about 12.5 million children are hospitalized (8%) because of serious and/or complicated pneumonias. Pneumonia is the main cause of death in children under 5 years old, reaching 1.4 million deaths/year over all the world.

In Latin America, pneumonia is one of the most frequent causes of hospital admission for children under 5 years of age. Mortality varies from 4 to 300 deaths/1000 live births. Considering the Latin American countries, Chile and Uruguay have the lowest mortality rate related to Streptococcus pneumoniae , whereas Bolivia, Peru, and Guyana have the highest mortality rate.

In Chile, pneumonia is an important public health issue, with a rate per year of 2000 to 3000 cases per 100,000 children less than 2 years of age. Half of those who seek attention in the emergency room require admission to the hospital, most because of acute respiratory failure and suppurative complications. Estimation of the frequency in which bacterial pneumonias progress to parapneumonic effusion, or noncomplicated exudate, is about 0.6–5%. Empyema has been estimated at about 3.3 per 100,000 children with community-acquired pneumonia.

Pleural empyema is the main suppurated complication. Around 40% of children with pneumonia who require hospitalization present with pleural effusion, and up to 2% of these present with empyema. Its incidence is greater during winter and spring. Epidemiological reports from Europe and the United States have confirmed an increase of this complication over recent years.

Etiology

The agents most commonly involved in empyema are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pyogenes.

Currently, S. pneumoniae is the bacterial agent that causes most complicated pneumonias. The use of systematic conjugated vaccines against S. pneumoniae has modified their behavior, which may have been related to the recent appearance of serotypes related to a greater frequency of pulmonary suppuration (19A, 7F, 1, and 5). In spite of this, etiological identification by hemocultures and pleural fluid culture is low. It is possible to isolate this bacterium using hemoculture in up to 10% of children hospitalized with pneumonia. Nasopharyngeal culture does not yield further information about the etiology, because generally the isolated agents are commensal flora of the upper respiratory system. Determining the urinary antigen as a pneumococcus has a limited sensitivity and specificity. There is no solid basis to recommend the routine use of fiberoptic bronchoscopy with a protective catheter or bronchoalveolar lavage for children.

The use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for S. pneumoniae in pleural fluid samples has increased isolation in more than 75% of the cases. Pneumonia caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, as happens with anaerobic microorganisms, often tends to present complications with empyema, and to have a higher rate of positive cultures.

A study conducted in the United States between 1993 and 2001 showed an increase of 24% of cases of pneumonia with pulmonary empyema. After 2000, the cases reduced in rate because of the introduction of the anti-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Since 2002, and mainly among children under 1 year old, an increase of pneumonia resulting in pleural effusion caused by Staphylococcus aureus has been observed.

Among other microorganisms that may cause pleural effusion less frequently, such as virus (adenovirus, influenza, parainfluenza), we can mention Mycoplasma pneumoniae , which may present pleural effusion in 5–20% of the cases, but which rarely requires a pleurocentesis. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacilli are much less common than in the adult population, in which they must only be suspected in the presence of aspiration pneumonia, pulmonary abscesses, and subdiaphragmatic abscesses. Haemophilus influenzae is an infrequent etiological agent in empyemas, but it must be considered as a potential infectious agent.

Community-acquired strains of S. aureus resistant to methicillin that have emerged over recent years are responsible for serious suppurated pneumonias.

Empyema Physiopathology

Pleural space is virtual and is limited by the visceral and parietal pleura. There is a continuous fluid filtration process from the capillary space to the subpleural one, and to the pleural cavity, which depends on the balance between the hydrostatic and oncotic pressures of both spaces, in accordance with the Starling law.

The presence of bacteria activates the inflammatory cascade in mesothelial cells, which release cytokines that cause the appearance of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils in the pleural space, which breaks the balance between filtration and reabsorption of the pleural liquid. At the same time, the coagulation cascade activates, reducing fibrinolysis and fibrin deposit in the pleural space, which causes loculations or segmentations. This process causes an increase in the metabolic activity of inflammatory cells and bacteria, which initiates a decrease in pH and glucose levels of the pleural fluid, as well as an increase in the LDH concentration.

Pleural Effusion, Classification, and Progression Phases

Pleural empyema has different progression phases that are well defined and impact treatment success. This process is dynamic and can be approached through escalated treatments. The exudative phase is the starting phase, usually within the first 48 h of febrile progression; free and sterile fluid is present. In the fibrinopurulent phase, segmentations appear and loculations are formed in the pleural space. In the organization or late phase, fibroblasts and pleural enlargement appear. Nevertheless, children achieve a complete recovery and rarely present restrictive adherences that may compromise respiratory mechanics.

- 1.

Parapneumonic effusion : Accumulation of pleural fluid related to a pneumonia or pulmonary abscess. At first the exudate is sterile, with a pH > 7.2 and glucose >40 mg/dl. In adults it is related to an LDH < 1000 UI/l.

- 2.

Empyema: Pus presence in pleural fluid, bacteria in the direct study (Gram or acridine orange stain) or culture or pleural fluid pH < 7.20. The presence of one or more of these criteria sets the diagnosis of pleural empyema. Other biochemical characteristics may suggest empyema, but they do not determine it.

- 3.

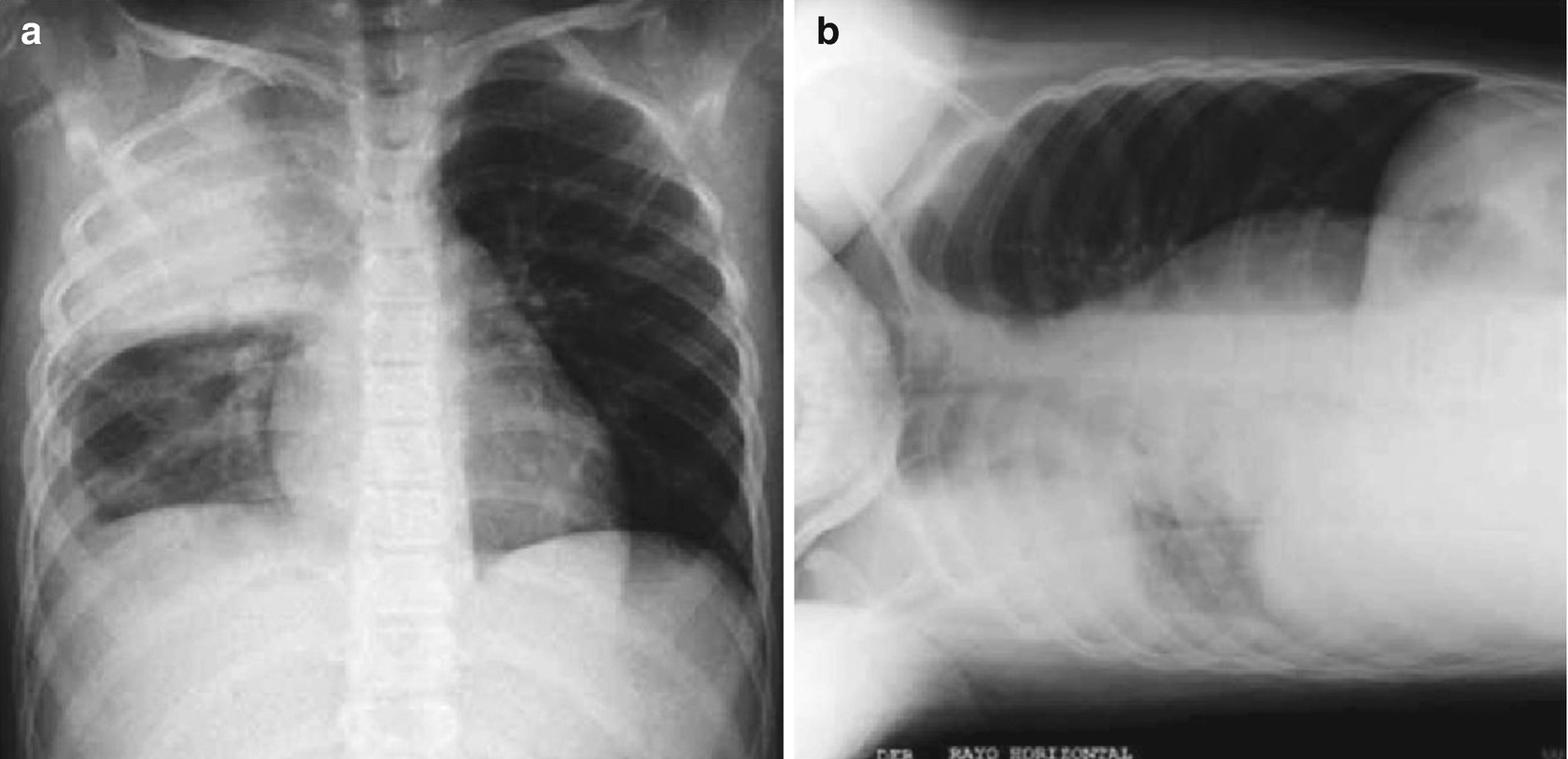

Segmented empyema : Occupation of the pleural space without displacement in the chest X-ray in lateral recumbent position with horizontal ray, or the presence of loculations with segmentations in the chest echography.

Clinical Manifestations

Complications of pneumonia must be suspected in every patient with probable bacterial community-acquired pneumonia who persist febrile after 48 h of adequate antibiotic treatment or who seek attention after 72 h of disease deterioration. The first possibility to rule out is pulmonary empyema.

The classic clinical picture includes lethargy, anorexia, persistent fever, usually above 39 °C with chills, cough (it is not the main symptom), and tachypnea. Chest pain and grunting may be present. Abdominal pain is a frequent symptom of pneumonia located in the lower lobes. In the most serious cases, the child may adopt an antalgic position (scoliosis toward the affected side).

The physical examination of the affected side will reveal a diminished chest excursion, dullness at percussion, and abolished normal breath sounds. In the upper limit of the effusion a pleural murmur may be heard, besides egophony and aphonic pectoriloquy. In infants and preschoolers, these signs are partially present and often absent. Dullness is the most important clinical sign. Large effusions may produce contralateral mediastinum deviation.

Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree