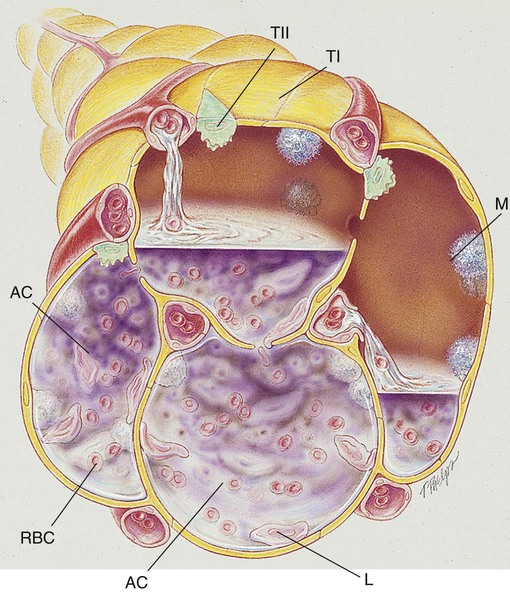

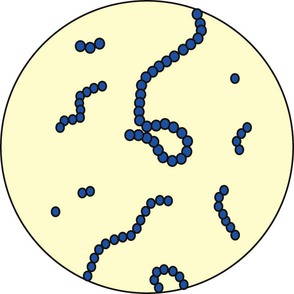

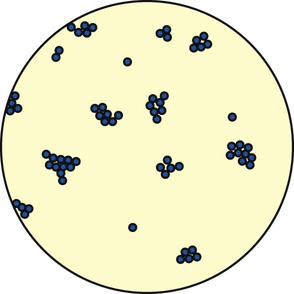

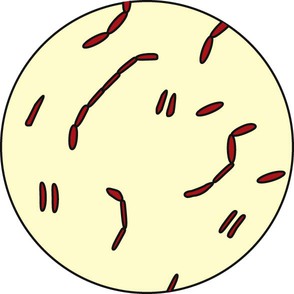

After reading this chapter, you will be able to: • List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with pneumonia. • Describe the causes and classifications of pneumonia. • List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with pneumonia. • Describe the general management of pneumonia. • Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study. • Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve. Pneumonia, or pneumonitis with consolidation, is the result of an inflammatory process that primarily affects the gas exchange area of the lung. In response to the inflammation, fluid (serum) and some red blood cells (RBCs) from adjacent pulmonary capillaries pour into the alveoli. This process of fluid transfer is called effusion. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes move into the infected area to engulf and kill invading bacteria on the alveolar walls. This process has been termed surface phagocytosis. Increased numbers of macrophages also appear in the infected area to remove cellular and bacterial debris. If the infection is overwhelming, the alveoli become filled with fluid, RBCs, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and macrophages. When this occurs, the lungs are said to be consolidated (Figure 15-1). Atelectasis is often associated with patients who have aspiration pneumonia. The major pathologic or structural changes associated with pneumonia are as follows: Pneumonia is an insidious disease because its symptoms vary greatly depending on the patient’s specific underlying condition and the type of organism causing the pneumonia. Often what is initially thought to be a cold or the flu can in fact be a much more serious pulmonary infection. The early recognition and treatment of pneumonia provide the best chance for a full recovery. There are over 30 causes of pneumonia. The major ones are listed in Box 15-1 and are discussed in the following paragraphs. Streptococcus pneumoniae accounts for more than 80% of all the bacterial pneumonias. The organism is a gram-positive, nonmotile coccus that is found singly, in pairs (called diplococci), and in short chains (Figure 15-2). The cocci are enclosed in a smooth, thick polysaccharide capsule that is essential for virulence. There are more than 80 different types of S. pneumoniae. Serotype 3 organisms are the most virulent. Streptococci are generally transmitted by aerosol from a cough or sneeze of an infected individual. Most strains of S. pneumoniae are sensitive to penicillin and its derivatives. S. pneumoniae also is commonly cultured from the sputum of patients having an acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. There are two major groups of Staphylococcus: (1) Staphylococcus aureus, which is responsible for most “staph” infections in humans, and (2) Staphylococcus albus and Staphylococcus epidermidis, which are part of the normal skin flora. The staphylococci are gram-positive cocci found singly, in pairs (called diplococci), and in irregular clusters (Figure 15-3). Staphylococcal pneumonia often follows a predisposing virus infection and is seen most often in children and immunosuppressed adults. S. aureus is commonly transmitted by aerosol from a cough or sneeze of an infected individual and indirectly via contact with contaminated floors, bedding, clothes, and the like. Staphylococci are a common cause of hospital-acquired pneumonia and are becoming increasingly antibiotic resistant—thus the term multiple drug–resistant S. aureus (MDRSA) organisms (some centers shorten this acronym to MRSA). The major gram-negative organisms responsible for pneumonia are rod-shaped microorganisms called bacilli (Figure 15-4). The bacilli described in the following sections are frequently seen in the clinical setting.

Pneumonia

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

Etiology and Epidemidogy

Bacterial Causes

Gram-Positive Organisms

Streptococcal pneumonia

Staphylococcal pneumonia

Gram-Negative Organisms

Pneumonia