Figure 37.1

After localization of the empyema via needle puncture, a 4 cm skin incision is made, followed by a rib resection of 2–3 cm (Fig. 37.1b). After the chest cavity is opened, the pleura parietalis should be resected in the involved area. The tissue should be sent for bacterial and histologic workup. With suction and irrigation, the cavity is washed out with 0.9 % sodium chloride (normal saline) after being drained

Empyema–VATS

In stage II, VATS is done via double-lumen intubation anesthesia; however, single-tube intubation initially is useful to enable preoperative bronchoscopy. Conversion to double-lumen intubation then enables one-lung ventilation and total collapse on the surgical side, affording the best overview and tissue protection. VATS is done via two to three 2-cm incisions, the first of which can be placed based on knowledge of the ultrasound or CT findings. All other incisions are made according to the intraoperative findings and under direct visualization via the thoracoscope.

Figure 37.3

With the help of grasping forceps, the pleural cavity is inspected, adhesions are taken down, and eventually multiple loculations can be addressed. Typical findings often are seen in the posterobasal area. All septations and cavities seen on the CT scan should be removed and drained. With early intervention, before severe fibrosis develops, decortication can be done via VATS or thoracotomy, supported by a grasping forceps. In patients without sepsis, the aim of the surgery is to completely free the lung and allow complete reexpansion by removing all inflammatory material. The final inspection should be done while watching for reexpansion of the atelectatic lung under controlled Valsalva after instillation of irrigation solution for underwater testing and identification of large parenchymal leaks. A targeted chest tube is placed to allow effective drainage, thus completing the procedure. During VATS, it is possible to obtain tissue samples (for bacteriologic workup, fluid chemistry, or histology) under visual control

Decortication

In the definitive stage III, the fibrous septum develops into a thick-walled pleural rind, eventually leading to one or more cavities.

Although thoracoscopic decortication (stage II–III) has been performed more often in recent years, radical and complete decortication remains the domain of open thoracotomy. The aim of this procedure is complete reexpansion of the lung with restoration of lung, diaphragm, and chest wall function. If the rind is enclosing a cavity, this procedure is called an empyemectomy. Decortication and empyemectomy are technically sophisticated and time-consuming procedures.

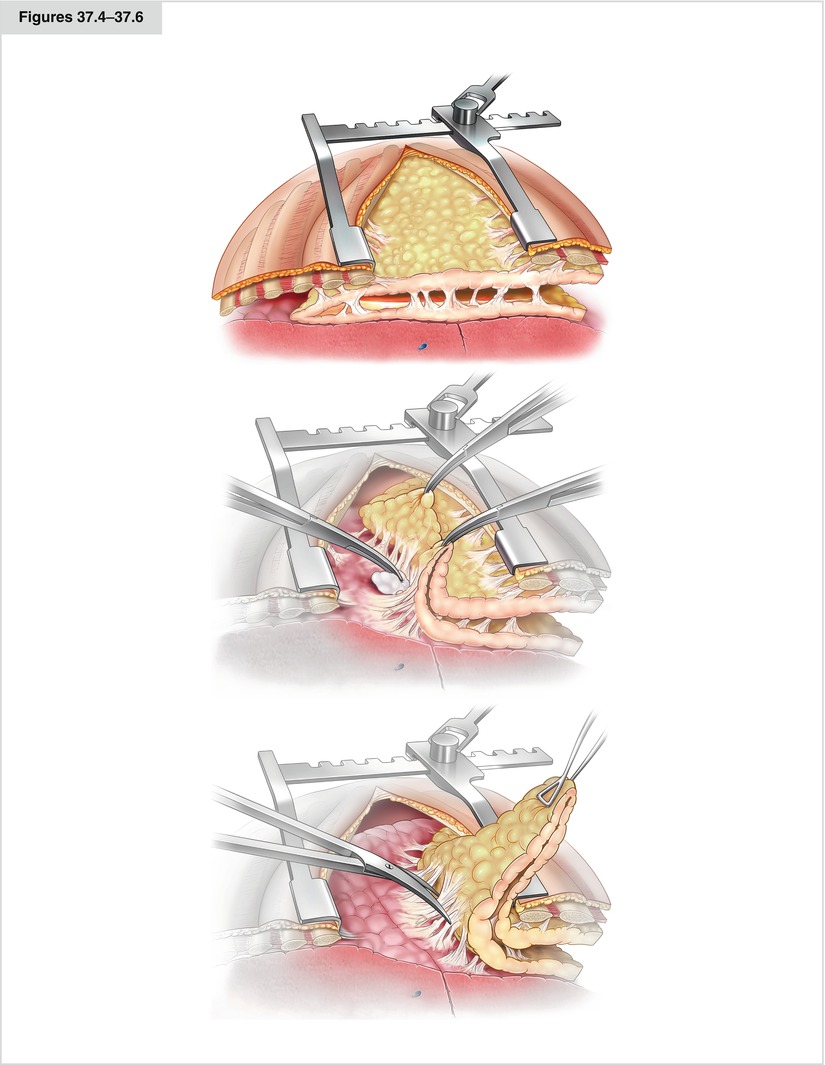

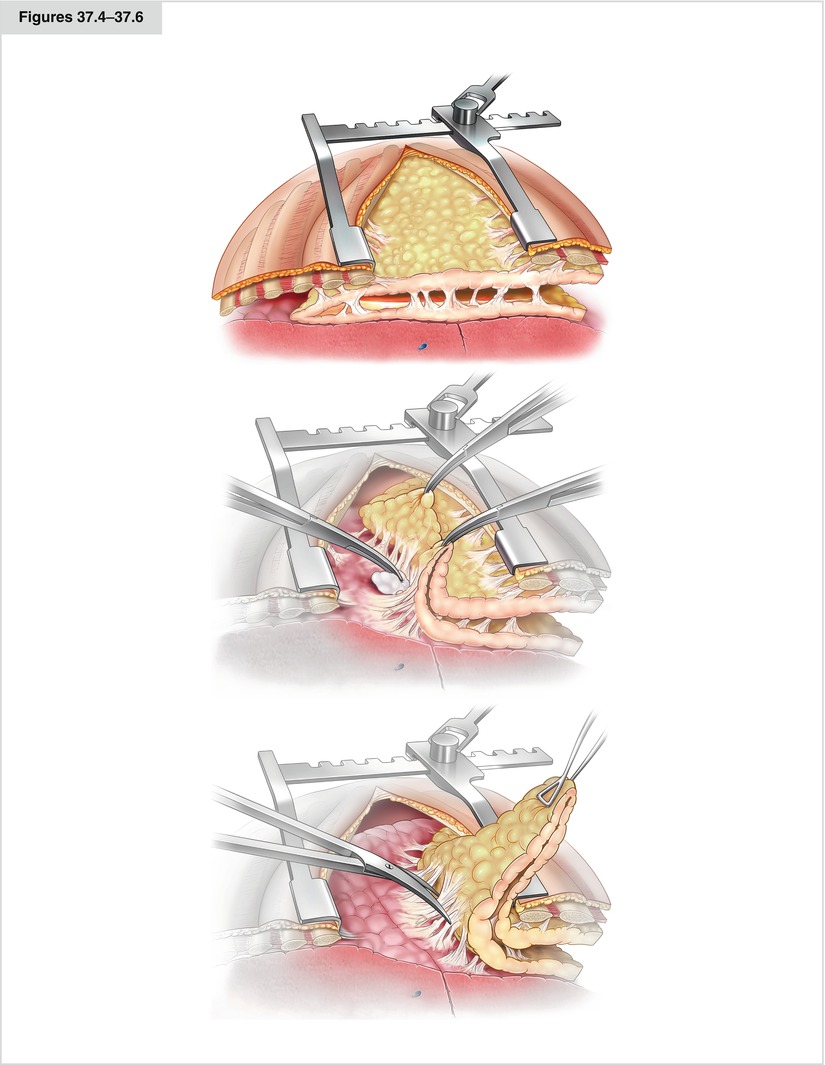

Figures 37.4–37.6

Ideally, the empyemectomy is done en bloc, that is, without opening the cavity. Where to place the incision for decortication should be determined carefully so that the basilar parts—the most affected areas—can be reached easily, to enable sufficient resolution of the diaphragm. A favorable incision for this procedure is the posterolateral thoracotomy in the sixth or seventh intercostal space (Fig. 37.4). Occasionally, an additional, more caudal incision is necessary for access to the diaphragmatic recesses. After blunt removal of the rind from the endothoracic fascia, the rind or the empyema sac must be tracked until the transition into intact pleura visceralis is seen. Here, the decortication starts with partially blunt and partially sharp removal of the rind from the pleura visceralis. The preparation is done with the help of a sponge stick swab (Fig. 37.5) or scissors (Fig. 37.6). In difficult areas, even a scalpel may be used. Opening of the empyema cavity should be avoided. Ideally, the organized tissue is removed in toto. If reexpansion of the lung cannot be achieved or is not expected because of a destroyed lobe, either parenchymal resection or cavity reduction via thoracoplastic or muscle flap must be considered. Regional muscle may be used as a rotational flap (apical: greater pectoral; basal: latissimus dorsi and anterior serratus). Contraindications for decortication are irreversible shrinkage of the parenchyma, high-grade stenosis of the bronchus, and high general surgical risk

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree