Pleural Effusion Secondary to Diseases of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Diseases of the gastrointestinal tract are sometimes associated with pleural effusion. In this chapter, the exudative pleural effusions resulting from pancreatic disease, intraabdominal abscesses, esophageal perforation, abdominal operations, diaphragmatic hernia, variceal sclerotherapy, hepatic transplantation, and disease of the biliary tract are discussed. Transudative pleural effusions that occur with cirrhosis and ascites are discussed in Chapter 9.

PANCREATIC DISEASE

Four different types of nonmalignant pancreatic disease can have an accompanying pleural effusion: acute pancreatitis, pancreatic abscess, chronic pancreatitis with pseudocyst, and pancreatic ascites.

Acute Pancreatitis

In older reports, the incidence of pleural effusion with acute pancreatitis was relatively low (3% to 17%) (1,2). More recent reports, however, have documented a much higher incidence of pleural effusion. Lankisch et al. (3) obtained computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest within 72 hours of admission in 133 consecutive patients with their first attack of acute pancreatitis and reported that 50% of the patients had a pleural effusion. The effusions were bilateral in 77%, left sided in 16%, and right sided in 8%. The thickness of the fluid on the CT scan was less than 10 mm in 32 patients, 1 to 2 cm in 18 patients, and greater than 2 cm in 16 patients with the CT scans (3).

The presence of a pleural effusion in patients with acute pancreatitis is an indication of more severe pancreatitis (4). In one series, the incidence of pleural effusion was 84% in 19 patients with severe pancreatitis but only 8.6% in 116 patients with mild pancreatitis (4). The presence of a pleural effusion is also associated with the development of a pseudocyst. In the series of Lankisch et al. (3), 29% of 66 patients with pleural effusions had pancreatic pseudocysts compared with 6% of 67 patients without pleural effusions.

The exudative pleural effusion accompanying acute pancreatitis results primarily from the transdiaphragmatic transfer of the exudative fluid arising from acute pancreatic inflammation and from diaphragmatic inflammation (2). Numerous lymphatic networks join on the peritoneal and pleural aspects of the diaphragm (1). Anatomically, the tail of the pancreas is in direct contact with the diaphragm. Hence, the exudate resulting from acute pancreatic inflammation, which is rich in pancreatic enzymes, enters the lymphatic vessels on the peritoneal side of the diaphragm and is conveyed to the pleural side of the diaphragm. Because this fluid contains high levels of pancreatic enzymes, the permeability of the lymphatic vessels is increased and fluid leaks from the pleural lymphatic vessels into the pleural space. The high enzymatic content of the pancreatic exudate may also cause partial or complete obstruction of the pleural lymphatic vessels that leads to more pleural fluid accumulation (1). Of course, the diaphragm itself may be inflamed from the adjacent inflammatory process, and this inflammation may increase the permeability of the capillaries in the diaphragmatic pleura. This mechanism cannot be entirely responsible for the pleural fluid accumulation, because the pleural fluid amylase concentration is almost always higher than the simultaneous serum amylase.

In the patient with acute pancreatitis, the clinical picture is usually dominated by abdominal symptoms including pain, nausea, and vomiting. At times, however, respiratory symptoms consisting of pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea may dominate the clinical picture. The chest radiograph may reveal, in addition to the small to moderate-sized pleural effusion, an elevated diaphragm, and basilar infiltrates (5). In addition, on ultrasound or fluoroscopy, the diaphragm is sluggish or immobile. The clinical picture may look much like that of pneumonia or pulmonary embolism complicated by pleural effusion.

The diagnosis is usually established by demonstrating an elevated serum amylase or lipase level in a patient with abdominal symptoms. In a patient with the typical clinical picture for pancreatitis, a thoracentesis need not be performed. If the patient has a large pleural effusion and the patient is dyspneic, a therapeutic thoracentesis should be performed to relieve the dyspnea. If the patient is persistently febrile, a thoracentesis should be performed to rule out an empyema.

In patients with acute pancreatitis, the pleural fluid amylase level is usually elevated (5). Light and Ball (6) reported on five patients with pleural effusions secondary to pancreatic disease, and in one of the patients, the pleural fluid amylase was originally within normal limits for serum, but subsequently the amylase level in this pleural fluid became elevated. The pleural fluid amylase level is usually higher than the serum amylase and remains elevated longer than the serum amylase (1,6). The pleural fluid amylase level in patients with acute pancreatitis tends to be lower than that in patients with chronic pancreatic disease (2). Pleural fluid levels of phospholipase A2 are also elevated in patients with acute pancreatitis (7).

Other characteristics of the pleural fluid with pancreatic disease are as follows. The pleural fluid is an exudate with high protein and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. Frequently, the pleural fluid is serosanguineous, and it can be bloody. The pleural fluid glucose level is comparable to that of the serum (6). The pleural fluid differential white blood cell (WBC) count usually reveals predominantly polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and the pleural fluid WBC can vary from 1,000 to 50,000 cells/mm3 (6).

In the patient with acute pancreatitis, the pleural effusion usually resolves as the pancreatic inflammation subsides. If the pleural effusion does not resolve within 2 weeks of treatment of the pancreatic disease, the possibility of a pancreatic abscess or a pancreatic pseudocyst must be considered.

Pancreatic Abscess

Pancreatic abscess usually follows an episode of acute pancreatitis. Typically, the acute pancreatitis initially responds to therapy, but 10 to 21 days later, the patient becomes febrile with abdominal pain and leukocytosis (8). The diagnosis is also suggested if a patient with acute pancreatitis does not respond to the usual therapy within several days (8). It is important to establish the diagnosis because the mortality rate approaches 100% if the abscess is not drained surgically (8). Both ultrasound (8) and abdominal CT scanning (9) are useful in establishing the diagnosis of pancreatic abscess preoperatively. Pleural effusion occurs commonly in patients with pancreatic abscess. In one series of 63 patients, 38% had pleural effusions on chest radiographs (8). Although pleural fluid findings were not described in this series, a patient described in a different paper had a high pleural fluid amylase level in a pleural effusion associated with a pancreatic abscess (10). The other complication that can cause a pleural effusion to persist in patients with acute pancreatitis is a pancreatic pseudocyst.

Pancreatic Pseudocyst and Chronic Pancreatic Pleural Effusion

A pancreatic pseudocyst is not a true cyst but rather a collection of fluid and debris rich in pancreatic enzymes near or within the pancreas. The walls consist of granulation tissue without an epithelial lining (11). Approximately 10% of patients with acute pancreatitis have a clinically significant pseudocyst (12). Approximately 5% of patients with a pancreatic pseudocyst have a pleural effusion (12). Pleural effusions due to pancreatic pseudocysts are relatively uncommon. Between 1983 and 1989, there were only seven cases at the Moffitt-Long and San Francisco General Hospitals (12).

The mechanism responsible for pleural effusion in patients with a chronic pseudocyst is the development of a direct sinus tract between the pancreas and the pleural space (10,13). When the pancreatic ductal system is disrupted, the extruded pancreatic fluid sometimes passes through the aortic or esophageal hiatus into the mediastinum. Once in the mediastinum, the process either can be contained, to form a mediastinal pseudocyst, or may decompress into one or both pleural spaces. Once fluid enters the pleural space, the pancreaticopleural fistula is likely to result in a massive chronic pleural effusion.

Most patients with chronic pancreatic pleural effusion are men. In more than 90% of male patients, the pancreatic disease is a result of alcoholism (12,14).

Chest symptoms usually dominate the clinical picture of the patient with chronic pancreatic disease and a pleural effusion (14). These patients report chest pain and shortness of breath. In one series of 101 patients from Japan, 42 complained of dyspnea and 29 complained of chest and back pain, whereas only 23 complained of upper abdominal pain (14). The explanation for the lack of abdominal symptoms is that the pancreaticopleural fistula decompresses the pseudocyst. Weight loss is common in patients with chronic pancreatic pleural effusions (12).

Chest symptoms usually dominate the clinical picture of the patient with chronic pancreatic disease and a pleural effusion (14). These patients report chest pain and shortness of breath. In one series of 101 patients from Japan, 42 complained of dyspnea and 29 complained of chest and back pain, whereas only 23 complained of upper abdominal pain (14). The explanation for the lack of abdominal symptoms is that the pancreaticopleural fistula decompresses the pseudocyst. Weight loss is common in patients with chronic pancreatic pleural effusions (12).

Pleural effusion is usually large, sometimes occupying the entire hemithorax. In most cases the effusion is unilateral and left sided, but approximately 20% are unilateral and right sided. Fifteen percent are bilateral (12,14). If a therapeutic thoracentesis is performed, the pleural effusion reaccumulates rapidly. In one patient, more than 13 L of pleural fluid was removed during three separate thoracenteses over a short period (15). Because chest symptoms dominate the clinical picture and some patients have no history of prior pancreatic disease, the diagnosis is easily missed unless the pleural fluid amylase is measured.

The diagnosis of a chronic pancreatic pleural effusion should be suspected in any individual with a large pleural effusion who appears to be chronically ill or has a history of pancreatic disease or abdominal trauma (16). Many patients have no history of pancreatic disease (12). The best screening test for chronic pancreatic pleural effusion is to measure the pleural fluid amylase. The pleural fluid amylase is usually markedly elevated (>1,000 U/L) (16), whereas the serum amylase may be normal or mildly elevated (16). An elevated pleural fluid amylase level is not diagnostic of pancreatic disease, as discussed in Chapter 7.

The other main diagnosis to consider in a patient with a chronic pleural effusion with a high amylase level is malignant disease. Approximately 10% of patients with a malignant pleural effusion have an elevated pleural fluid amylase level (6). With malignancy, the cytology is frequently positive. In addition, it is uncommon to have a malignant pleural effusion with an amylase above 1,000 U/L. If there is difficulty in distinguishing between these two entities, the differentiation can be made by obtaining amylase isoenzymes on the pleural fluid. With malignant effusions, the amylase is of the salivary rather than the pancreatic type (17).

Diagnosis can usually be established by CT of the chest and abdomen, which frequently shows both the pseudocyst and the sinus tract (12). Magnetic resonance imaging is complimentary to CT in establishing the presence of pseudocyst and the site of the ductal disruption (18). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) also plays an important role in the evaluation and management of patients with pancreaticopleural fistula. ERCP is useful in delineating the ductal structure, the pseudocyst, and the fistulous connection to the pleura through the sinus tract (12). The greatest utility for ERCP is in defining the precise anatomic relationship preoperatively so that a direct and expeditious surgical procedure can be planned. Recently, some patients have been successfully treated by placing stents in the pancreatic duct at the time the ERCP is performed (19,20). In one series (18), five of six patients were successfully treated with a stent.

The initial therapy of a patient with a pancreatic pseudocyst and a pleural effusion should probably be nonoperative. The theory behind conservative therapy is that if pancreatic secretions are minimized, the pseudocyst will regress and the sinus tract will close. Accordingly, a nasogastric tube is inserted and the patient is given intravenous hyperalimentation. It is probable that the patients are benefited if they are given somatostatin or octreotide, a synthetic analog of somatostatin (21). Somatostatin has numerous inhibitory actions on gastrointestinal functions, one of which is its inhibitory effect on pancreatic exocrine secretion (12). It has been shown that somatostatin decreases the output from an external pancreatic fistula by more than 80% (22). Some authors recommend serial thoracentesis and subsequent tube thoracostomy if the effusions recur, but there is no evidence that such procedures are beneficial.

If after 2 weeks, the patient remains symptomatic and the pleural fluid continues to accumulate, surgical intervention should be considered. Approximately 50% of patients require surgery. Surgery is more likely to be required in patients with more severe pancreatic disease (21). Before surgery, an endoscopic retrograde pancreatogram and an abdominal CT scan should be performed to aid in planning the surgical procedure (23). For example, if a leak from the duct or pseudocyst is demonstrated in the distal portion of the gland, distal pancreatectomy will be curative. If a direct pancreatic duct leak is found in the more proximal portion of the gland, without a pseudocyst, a direct anastomosis between the leak and a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop or a Whipple resection should be considered. Conversely, if a large cyst is present within the body of the gland, internal drainage should be performed either into the stomach or with a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop. Procedures that do not focus on removal of the disrupted portion of the gland or on drainage

of the pseudocyst usually fail. If the preoperative ERCP is unsuccessful, pancreatography may be performed at the time of surgery (12).

of the pseudocyst usually fail. If the preoperative ERCP is unsuccessful, pancreatography may be performed at the time of surgery (12).

An alternative approach to the patient with a pancreatic pseudocyst is to drain the pseudocyst percutaneously. Under CT guidance, a catheter is introduced through the anterior abdominal wall, and then through the anterior and then the posterior wall of the stomach into the pseudocyst cavity. Side holes are cut into the part of the catheter that lies in the pseudocyst and that which lies in the stomach. Maintenance of this drainage for 15 to 20 days is thought to create a fistulous tract between the pseudocyst and stomach akin to surgical marsupialization. In one series, 20 of 26 patients (77%) were cured by this procedure (24). To my knowledge, there are no randomized studies comparing the results with surgery and with percutaneous drainage of pseudocysts.

The prognosis of patients with pancreaticopleural fistula appears to be favorable (12). In the series of 96 patients reviewed by Rockey and Cello (12), the overall mortality rate was 5%, and 3 patients died of unrelated illnesses during their follow-up period. Both patients who died as a direct result of the pancreatic process were managed conservatively and died of sepsis.

In patients with chronic pleural effusions secondary to pancreatic disease, the pleural surfaces may become thickened, and in several patients, decortications have been performed (25). However, because the pleural thickening gradually improves spontaneously, decortication should be delayed for at least 6 months following definitive treatment of the pancreatic disease to ascertain whether the pleural disease will resolve spontaneously.

One rare complication of pancreatic pleural effusion is the development of a bronchopleural fistula. Kaye (1) reported one such patient in whom the development of the bronchopleural fistula was heralded by the expectoration of copious quantities of clear yellow fluid. In this situation, chest tubes should be inserted immediately to drain the pleural space and to protect the lung from the fluid with its high enzymatic content.

Pancreatic Ascites

Some patients with pancreatic disease develop ascites characterized by high amylase and protein levels (21,26). The genesis of the ascites is through leakage of fluid from a pseudocyst directly into the peritoneal cavity or a sinus tract from the pseudocyst into the peritoneal cavity. If such a patient should happen to have a defect in his diaphragm, he will develop a large pleural effusion as a result of the flow of fluid from the peritoneal to the pleural cavity in the same way that pleural effusions develop secondary to ascites due to cirrhosis (see Chapter 9). Approximately 20% of patients with pancreatic ascites have a pleural effusion (26).

Most patients with pancreatic ascites and pleural effusion are initially thought to have cirrhosis and ascites. The diagnosis is easily established if amylase determinations are made on the peritoneal and pleural fluid in such patients (26). Most patients have a protein level above 3.0 g/dL in their ascitic fluid. The treatment for pancreatic ascites is the same as for pancreatic pleural effusion, except that serial paracenteses rather than serial thoracenteses are performed (26).

SUBPHRENIC ABSCESS

Subphrenic abscess continues to be a significant clinical problem despite the development of potent antibiotics.

Incidence

In most large medical centers, between 6 and 15 subphrenic abscesses are seen each year (27—29). Subphrenic abscesses are discussed in this chapter because a pleural effusion is present in approximately 80% of cases.

Pathogenesis

Approximately 80% of subphrenic abscesses follow intraabdominal surgical procedures (30,31). Splenectomy is likely to be complicated by a left subphrenic abscess (31), as is gastrectomy. Deck and Berne (32) noted a high incidence of subphrenic abscess after exploratory laparotomy for trauma; in their study, 59% of subphrenic abscesses occurred after such an operation. Overall, approximately 1% of abdominal operations are complicated by subphrenic abscess (29). Sanders (29) reviewed the incidence of subphrenic abscesses following 1,566 abdominal surgical procedures at the Radcliíffe Infirmary in 1965 and found 15 patients with subphrenic abscess. Sanders also reviewed the cases of 23 patients with pleural effusion following intraabdominal surgical procedures during the same period. He found that 12 of the 23 patients had definite subphrenic abscesses, and he believed that another 5 patients possibly had subphrenic abscesses.

Subphrenic abscess may also occur without antecedent abdominal surgical procedures. It may result from processes such as gastric, duodenal, or appendiceal perforation; diverticulitis; cholecystitis;

pancreatitis; or trauma (30). In such patients, the diagnosis of subphrenic abscess is frequently not considered. In one series of 22 patients in whom abscesses occurred without antecedent abdominal operations, the diagnosis was established before the patient’s death in only 41% (30).

pancreatitis; or trauma (30). In such patients, the diagnosis of subphrenic abscess is frequently not considered. In one series of 22 patients in whom abscesses occurred without antecedent abdominal operations, the diagnosis was established before the patient’s death in only 41% (30).

The pathogenesis of the pleural effusion associated with subphrenic abscess is probably related to inflammation of the diaphragm. Although Carter and Brewer (27) proposed that the pleural effusion arose from the transdiaphragmatic transfer of abscess material by the lymphatic vessels, this hypothesis is unlikely because fluid from these pleural effusions is only rarely culture positive. If the pleural effusion arose from the transdiaphragmatic transport of abscess material, bacteria as well as leukocytes should be transported. The diaphragmatic inflammation resulting from the adjacent abscess probably increases the permeability of the capillaries in the diaphragmatic pleura and causes pleural fluid to accumulate.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical picture of a patient with subphrenic abscess can be dominated by either chest or abdominal symptoms. In the series of 125 cases of Carter and Brewer (27), chest findings dominated the clinical picture in 44% of patients. The main chest symptom is pleuritic chest pain. Radiographic abnormalities include pleural effusion, basal pneumonitis, compression atelectasis, and an elevated diaphragm on the affected side. Pleural effusions occur in 60% to 80% of patients and are usually small to moderate in size, but may be large, occupying more than 50% of the hemithorax (27,28,31,32,33).

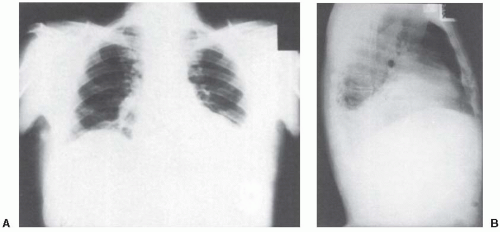

FIGURE 18.1 ▪ Posteroanterior chest radiograph A: and left lateral radiograph B: demonstrating elevated left diaphragm and blunting of the left diaphragm posteriorly. |

Most patients with postoperative subphrenic abscesses have fever, leukocytosis, and abdominal pain (27,28,29), but frequently no localizing signs or symptoms are present. The symptoms and signs of subphrenic abscess are variable. In a series of 60 patients, 37% had no abdominal pain, 21% had no abdominal tenderness, 15% had no temperature elevation greater than 39°C, and 8% had no leukocytosis above 10,000/mm3 (28). The interval between the surgical procedure and the development of the subphrenic abscess is usually 1 to 3 weeks but can be as long as 5 months (30, 31).

Examination of the pleural fluid from patients with subphrenic abscesses usually reveals an exudate with predominantly polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Although the pleural fluid WBC may approach or even exceed 50,000/mm3, the pleural fluid pH and glucose level remain above 7.20 and 60 mg/dL, respectively. It is distinctly uncommon for the pleural fluid to become infected (27). However, empyemas have resulted from contamination of the pleural space when the abscesses were drained percutaneously (34).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of subphrenic abscess should be considered in any patient who develops a pleural effusion several days or more after an abdominal surgical procedure or in any other patient who has an undiagnosed exudative pleural effusion containing predominantly polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The chest radiographs from such a patient are shown in Figure 18.1.

This patient had left-sided chest pain and a low-grade fever without any abdominal symptoms. Thoracentesis revealed an exudate with a WBC of 29,000, an LDH level of 340 IU/L (upper normal limit for serum 300 IU/L), a glucose level of 117 mg/dL, and a pH of 7.36. He was treated with parenteral antibiotics for a presumed parapneumonic effusion but had little clinical response. Two subsequent thoracenteses revealed similar pleural fluid findings. Two weeks after admission, a gallium scan revealed increased uptake of the gallium in the left upper quadrant (Fig. 18.2). At laparotomy, this patient was found to have a left subphrenic abscess resulting from a colonic perforation secondary to a colonic carcinoma. At no time did this patient have more than mild left upper quadrant tenderness.

This patient had left-sided chest pain and a low-grade fever without any abdominal symptoms. Thoracentesis revealed an exudate with a WBC of 29,000, an LDH level of 340 IU/L (upper normal limit for serum 300 IU/L), a glucose level of 117 mg/dL, and a pH of 7.36. He was treated with parenteral antibiotics for a presumed parapneumonic effusion but had little clinical response. Two subsequent thoracenteses revealed similar pleural fluid findings. Two weeks after admission, a gallium scan revealed increased uptake of the gallium in the left upper quadrant (Fig. 18.2). At laparotomy, this patient was found to have a left subphrenic abscess resulting from a colonic perforation secondary to a colonic carcinoma. At no time did this patient have more than mild left upper quadrant tenderness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree