I. Perioperative cardiac risk.

A key factor in achieving excellent results from elective vascular surgery, open or endovascular, is accurate assessment of anesthetic risk. Although clinical sense and experience contribute a great deal to an initial impression of anesthetic risk, more objective data also assist with assess ment of operative risk. Historically, preoperative physical condition was correlated with anesthetic morbidity and mortality using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification. This grading system refers only to a patient’s overall physical condition and does not consider the type of anesthesia, extent of operation, or experience of the surgeon. There are five levels of ASA classification, with 1 indicating a healthy individual and 5 noting extreme coexisting medical conditions. The letter “e” is added to indicate an emergency procedure. In 1977, Goldman developed a more involved scoring system to evaluate perioperative cardiac risk from 1,000 patients having undergone general surgical procedures. When this system was applied prospectively to 99 patients undergoing elective aortic surgery, the rates of cardiac complications were higher than those in the original study of general surgical procedures. This finding was among the first reporting the high incidence of significant coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients undergoing vascular procedures.

A. Evidence-based algorithm.

MI is the leading cause of death following vascular procedures, occurring in 3-6% of elective cases. Additionally, some degree of myocardial ischemia is present following 20-40% of vascular procedures, depending upon how aggressively the diagnosis is pursued. Hertzer and colleagues of the Cleveland Clinic defined the prevalence of coronary artery disease in vascular patients, demonstrating

that severe but correctable CAD existed in nearly one-third of patients presenting for surgical treatment of peripheral vascular disease (abdominal aortic aneurysm, 32%; cerebrovascular disease, 26%; arteriosclerosis of the lower

limbs, 28%). Severe, correctable CAD was present in about 50% of patients with angina pectoris and 30% with a previous myocardial infarction.

Following this seminal report came more than two decades of study aimed at reducing cardiac morbidity and mortality around the time of peripheral vascular intervention. Much of this effort focused on identifying those with silent but correctable coronary disease prior to the planned procedure; the assumption being that in such individuals, coronary angiography followed by revascularization would reduce perioperative risk and increase survival. While this approach emphasizing coronary revascularization was beneficial in subsets of patients, such as in the Coronary Artery Surgery study (CASS), it is not applicable to all those undergoing vascular procedures. In fact, more recent publication of the Coronary Artery Revascularization Prophylaxis (CARP) trial showed that among patients with stable cardiac symptoms, preoperative coronary revascularization does not improve short- or long-term survival. Findings from the CARP study and others like it have resulted in more balanced recommendations that propose a more selective role of preoperative coronary revascularization while emphasizing periprocedural medical therapy (e.g., beta-blockers, statins, and ACE inhibitors). The following paragraphs outline the contemporary guidelines on perioperative cardiac risk assessment.

1. Eagle and associates identified key clinical markers of increased cardiac risk in patients undergoing vascular operations (Eagle criteria): (a) angina pectoris, (b) prior MI, (c) congestive heart failure, (d) diabetes mellitus, and (e) age greater than 70 years. The risk for a perioperative cardiac event increases with the number of criteria present (

Table 8.1). With three or more, the risk of a perioperative cardiac event is 30%, with 77% of these patients having severe CAD on coronary angiography. Although the Eagle criteria are largely of historical importance, they provide a very good and concise listing of key clinical factors to be considered prior to elective vascular procedures.

2. In 1996 the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association published guidelines for preoperative cardiac evaluation. These guidelines were revised in 2002 and again in 2007 to provide a framework for considering cardiac risk associated with non-cardiac surgery. Three prominent themes from the updated 2007 guidelines include:

Preoperative coronary intervention is rarely necessary unless otherwise indicated independent of the planned procedure.

Preoperative evaluation is not performed to “give clearance to operate,” but instead should provide an assessment of the patient’s medical condition and present a risk profile that can be used to make treatment decisions.

No preoperative testing should be performed unless it is likely to influence patient treatment (e.g., if it will actually change the perioperative management).

Additionally, the 2007 guidelines were converted from tabular format to listing of recommendations written in sentences to express more complete thought. Also, a clearer explanation of the clinical evidence supporting each guideline is provided using

levels of evidence and classification of recommendations (

Table 8.2). Specifically, levels of clinical evidence A, B, or C are cross-referenced with classification of recommendations (I, IIa, IIb, and III) to give the provider an estimate of the certainty and size of each guideline. For example, level A evidence indicates the strongest estimate of certainty coming from evaluation of several patient groups with a consistency of direction and magnitude of effect. Level A evidence is supported by more than one randomized clinical trial or a meta-analysis, while level B evidence stems from a single randomized trial or several nonrandomized trials. It is important to note that guidelines supported by level B or C evidence are not necessarily weak. Some clinical questions are not well suited for clinical trials, or the optimal time to perform such a trial may have passed. In some cases the clinical consensus in favor of a test or therapy is so strong that there is no need for investment to initiate a trial to prove the point. In such instances

classification of recommendations is useful, as it provides a broader perspective than just the published or hard evidence for or against a given test or therapy (

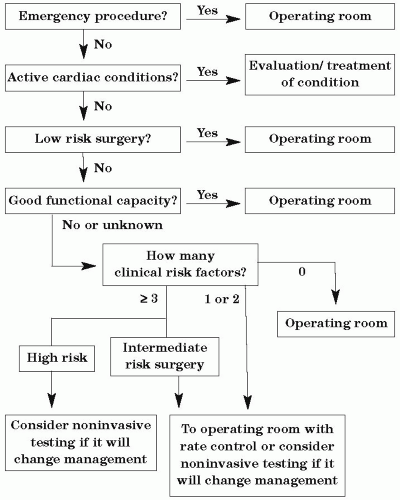

Table 8.2). Armed with this basic understanding of levels of evidence and classification of recommendations, the provider can proceed in taking the patient’s medical history and perform a review of systems, focusing on three areas that relate directly to the cardiac evaluation algorithm in the 2007 guidelines (

Fig. 8.1):

Identification of

active cardiac conditions (

Table 8.3)

Identification of

clinical risk factors for cardiovascular events (

Table 8.3)

Evaluation of the patient’s

functional capacity (Table 8.4)

Active cardiac conditions (formerly major predictors in the 2002 guidelines) represent conditions that if present should be thoroughly evaluated and treated

before noncardiac surgery, even if it means a delay in or cancellation of a nonemergent case (

Fig. 8.1). These conditions include unstable coronary syndromes, decompensated heart failure, significant arrhythmias, and severe valvular disease. This guideline represents a class I recommendation supported by level B evidence. The patient should also be evaluated for the presence of one or more of the five

clinical risk factors (formerly

intermediate predictors) recognized in the 2007 guidelines. These include history of ischemic heart disease, compensated heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes or renal insufficiency (

Table 8.3). These factors are used in the final step of the cardiac evaluation and care algorithm in managing patients undergoing a high-risk surgery who have an unknown or poor functional capacity (

Fig. 8.1).

Estimation of

functional capacity is also critical and can be accomplished by simply interviewing the patient about his or her living situation and daily activities. Functional capacity is expressed in

metabolic equivalents (METs) and has been shown to correlate well with oxygen uptake by formal treadmill testing (

Table 8.4). In patients who have moderate or better functionality (>4 METs) without symptoms, preoperative management is unlikely to be changed based on additional cardiac testing. In contrast, cardiac risk is increased in persons who are unable to meet a 4-MET demand, such as performing daily activities, and such persons may benefit from preoperative cardiac testing depending upon the magnitude of the planned procedure (

Fig. 8.1). Once the provider has established the presence or absence of active cardiac conditions and clinical risk factors and assessed the patient’s functional status, he or she can move to the

cardiac evaluation and care algorithm to determine the need for and appropriateness of preoperative cardiac testing. This five-step approach provided as part of the 2007 guidelines, is as follows:

Step 1. Is the planned procedure an emergency? If so then the patient should proceed to the operating room (class I recommendation with level C evidence). In these cases the situation does not allow for further cardiac assessment, and recommendations will focus on perioperative optimization with medications and monitoring and surveillance for cardiac events in the postoperative period. If the procedure is not emergent then the provider should proceed to the next step.

Step 2. Does the patient have active cardiac conditions? If so then these should be evaluated and treated prior to the planned procedure (class I recommendation with level B evidence). Consideration of proceeding with the operation may be given after these conditions have been evaluated and treated. If the patient does not have any identifiable active cardiac conditions the provider should proceed to the next step.