18 Pericardiocentesis

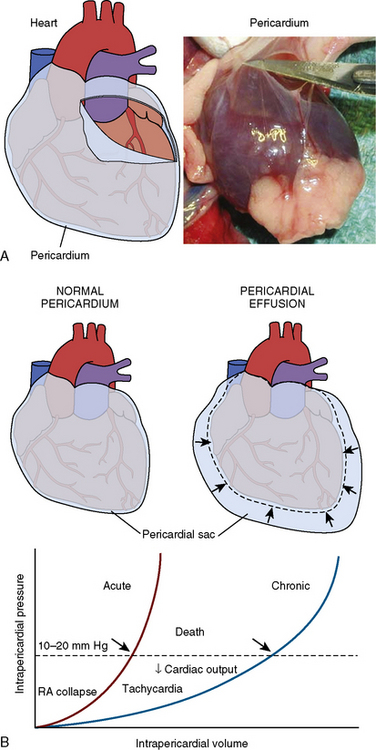

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening disorder that can result from any condition that causes a pericardial effusion. Although the most frequent cause is malignancy, tamponade may also occur from pericarditis (e.g., viral, uremic, inflammatory, or idiopathic), aortic dissection (with disruption of the aortic annulus), or ventricular rupture from myocardial infarction. In the cardiac catheterization laboratory, tamponade can result as a complication of a variety of invasive procedures and lead to rapid demise of the patient due to the swift accumulation of fluid in a poorly compliant pericardial space. Prompt recognition of the salient hemodynamic features and immediate pericardiocentesis are essential to the successful treatment of cardiac tamponade. The rate of pericardial fluid accumulation relative to the stiffness of the pericardium determines how quickly the clinical syndrome of tamponade will occur. Figure 18-1 shows a normal pericardial membrane and the mechanisms of pericardial tamponade.

Diagnosis of Tamponade

Echocardiography

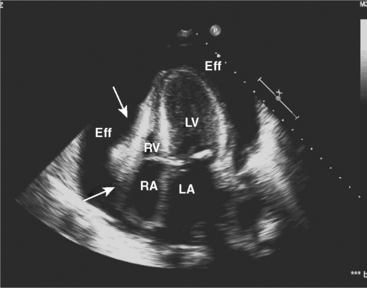

Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography are commonly used for diagnosing cardiac tamponade. Specific signs of tamponade include collapse of the right atrium and right ventricle, ventricular septal shifting with respiration, and plethora (enlargement) of the inferior vena cava (Fig. 18-2). Respiratory variation in the Doppler mitral inflow is a highly sensitive measure that occurs early in tamponade, and may precede changes in cardiac output, blood pressure, and other echocardiographic findings.

Hemodynamics

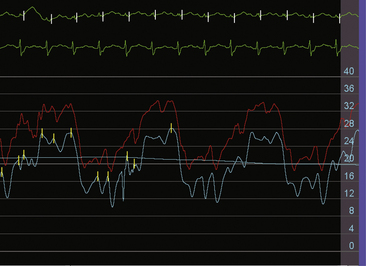

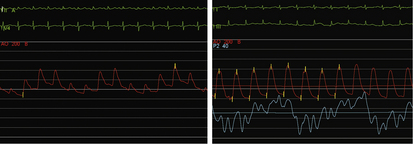

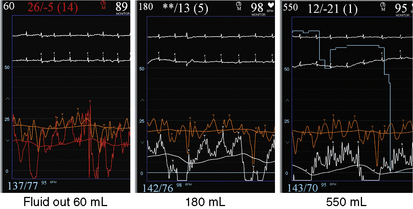

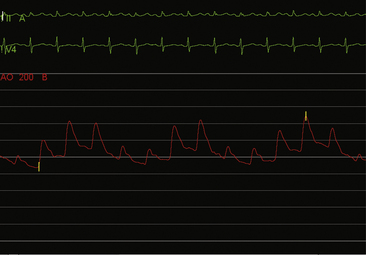

The invasive hemodynamic hallmarks of cardiac tamponade include pulsus paradoxus on the arterial tracing (Fig. 18-3) and prominent x descents and blunted y descents in the atrial pressure tracings (Fig. 18-4). Preservation of the x descent occurs because of the decrease in intracardiac volume during systolic ejection, which leads to a temporary reduction in intrapericardial and right atrial pressures (See Kern (2011) The Cardiac Catheterization Handbook 5th ed., Chapter 3 Hemodynamics). Elevated intrapericardial pressure impairs ventricular filling during the remainder of the cardiac cycle, resulting in blunting of the y descent. In patients with cardiac tamponade, the driving pressure to fill the left ventricle falls during inspiration. Consequently, there is a reduction in left ventricular filling and stroke volume, which manifests as a decrease in aortic pulse pressure during inspiration in a manner analogous to the bedside finding of pulsus paradoxus (see Fig. 18-3).

Figure 18-3 Arterial pressure in a patient with dyspnea at rest demonstrating pulsus paradoxus due to cardiac tamponade.

On relief of pericardial pressure and removal of the effusion, right atrial pressure and pericardial pressure fall usually to normal values if no residual pericardial disease is present (Fig. 18-5). However, in some cases, although pericardiocentesis empties the pericardial space and pericardial pressure falls to near zero, right atrial pressure may be unaffected, signifying the syndrome of effusive-constrictive pericardial disease (Fig. 18-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree