42 Pericardial Disease

Clinical Features and Treatment

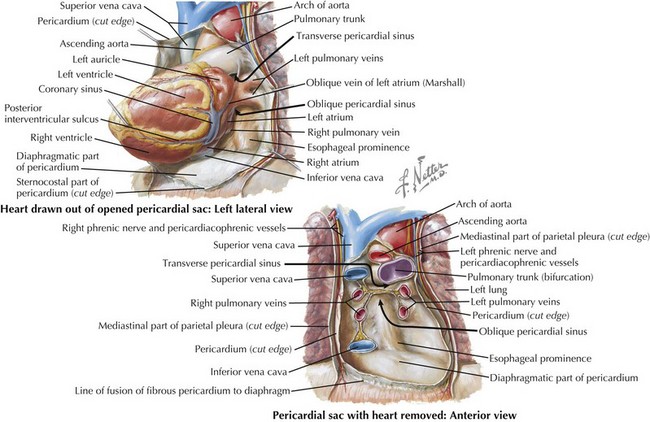

The pericardium is a two-layered sac that encircles the heart (Fig. 42-1). The visceral pericardium is a mesothelial monolayer that adheres to the epicardium. It is reflected back on itself at the level of the great vessels, where it joins the parietal pericardium, the tough fibrous outer layer. Under normal conditions, a small amount of fluid (approximately 5–50 mL) separates the two layers and decreases friction between them.

This chapter discusses the clinical features and treatment of four pathologic conditions involving the pericardium: acute pericarditis, chronic pericarditis, constrictive pericarditis, and pericardial effusions. The hemodynamic effects of pericardial pathology are discussed in Chapter 43.

Acute Pericarditis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

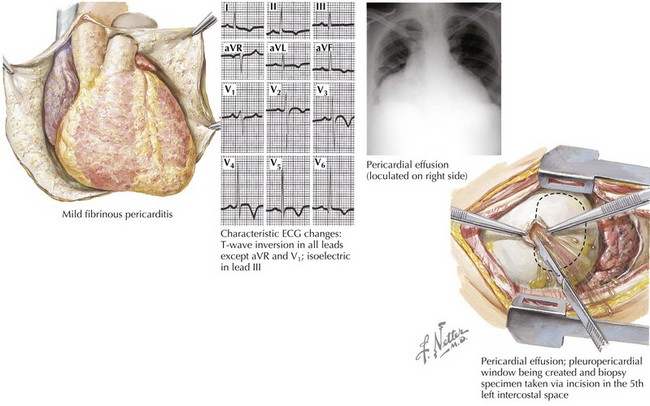

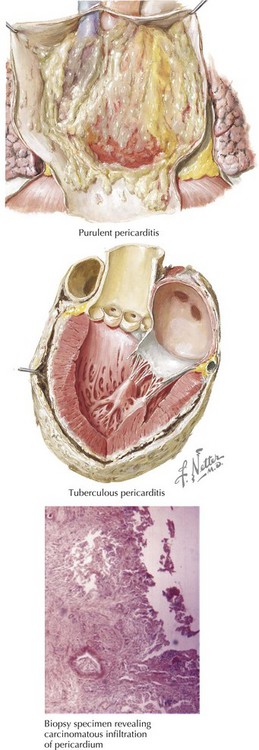

The most common presentation of a pericardial abnormality is acute pericarditis, inflammation of the pericardium (Fig. 42-2). In general, this is a self-limited disease that is responsive to oral anti-inflammatory medication. Acute pericarditis infrequently necessitates hospital admission. It is more common in men than in women and more common in adults than in children. The two most common causes of acute pericarditis in the United States are viral and idiopathic. Other causes include uremia, pericardiectomy associated with cardiac surgery, pulmonary embolism, collagen-vascular diseases, Dressler’s syndrome, malignancy, tuberculosis, fungus (e.g., histoplasmosis), parasites (e.g., ameba), myxedema, radiation, acute rheumatic fever, and trauma (Fig. 42-3).

Diagnostic Approach

The diagnosis of acute pericarditis is based on clinical criteria, but the ECG can make an important contribution. The lack of ECG changes cannot exclude the diagnosis of pericarditis. That said, most patients progress through one or more of the four stages of ECG changes commonly associated with the evolution of acute pericarditis (see Fig. 42-2 (ECG); Fig. 42-4). Stage I changes accompany the onset of chest pain and include the classic ECG changes associated with acute pericarditis: diffuse concave ST elevation with PR depression (see Chapter 4). Stage II occurs several days later and is represented by the return of ST segments to baseline and T-wave flattening. In stage III, T-wave inversion is seen in most leads. The ECG in stage IV shows the return of T waves to an upright position. The approximate time frame for passage through all four stages of ECG changes in most cases of acute pericarditis is 2 weeks.

Constrictive Pericarditis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

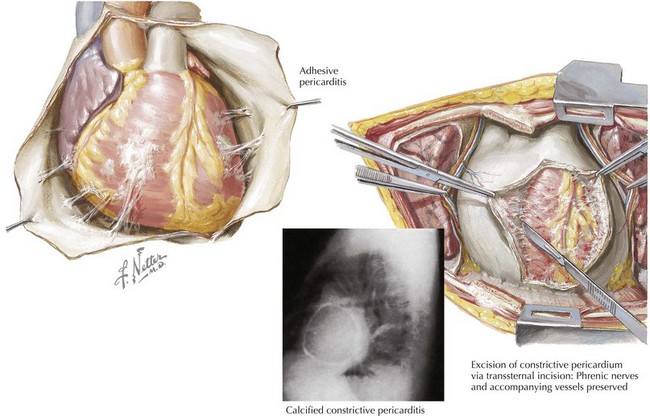

Constrictive pericarditis is characterized by a dense, fibrous thickening of the pericardium that adheres to and encases the myocardium, resulting in impaired diastolic ventricular filling (Fig. 42-5). The general paradigm is that constrictive pericarditis occurs over a period of years as a result of an acute injury (e.g., a viral infection) that elicits a chronic fibrosing reaction or as a result of a chronic injury that stimulates a persistent reaction (e.g., renal failure). Clinically, constrictive pericarditis generally is a chronic disease with symptom progression over a period of years. The presentation is that of right-sided heart failure and may resemble restrictive cardiomyopathy, cirrhosis, cor pulmonale, or other conditions. Because pericardial constriction is uncommon, patients occasionally are treated for an incorrect diagnosis (left- or right-sided heart failure, hepatic failure, or others) for years. Patients with pericardial constriction often have even been admitted to a hospital for symptoms attributed to other causes before a definitive diagnosis of constriction is made. Newer diagnostic technologies and a change in the predominant etiologies of constriction have increased the recognition of subacute presentations occurring over a period of months.

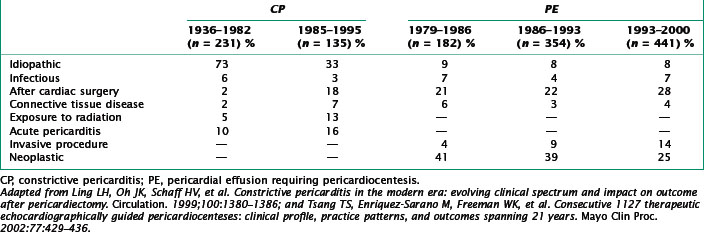

The most common causes of constriction in industrialized countries are cardiac surgery, mediastinal radiation, pericarditis, and idiopathic etiologies (Table 42-1). Other causes include infection (e.g., fungal or tuberculosis), malignancies such as breast cancer or lymphoma, connective tissue disease (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis), trauma, and drugs.