22 Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery Stenosis

Introduction

Introduction

Because of the long-term benefit of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) compared with medical therapy, CABG has been the standard treatment for unprotected LMCA stenosis.1–3 However, with the advancement of technique and equipment, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has been found to be feasible for patients with unprotected LMCA stenosis.3 In particular, the recent introduction of DESs, together with advances in peri-procedural and postprocedural adjunctive pharmacotherapies, has improved the outcomes of PCI for these complex coronary lesions.4–29 Therefore, in the recent updated guidelines, PCI for unprotected LMCA stenosis has still been indicated as class IIb for patients at a high surgical risk or emergent clinical situations such as bailout procedure or AMI as an alternative therapy to CABG.30 Patients with LMCA stenosis have been traditionally classified into two subgroups: (1) protected (a previous patent graft from CABG to one or more major branches of the left coronary artery) and (2) unprotected LMCA disease (without such bypasses). In this review, current outcomes of PCI with DES in a series of research studies conducted across several countries are evaluated.

Definition of Significant Left Main Coronary Artery Stenosis

Definition of Significant Left Main Coronary Artery Stenosis

Coronary angiography has been the standard tool to determine the severity of coronary artery disease. Although a traditional cut-off for significant coronary stenosis has been stenosis diameter of 70% in non-LMCA lesions, its cut-off in LMCA has been stenosis diameter of 50%. However, because the conventional coronary angiogram is only a lumenogram providing information about lumen diameter but yielding little insight into lesion and plaque characteristics themselves, it has several limitations caused by peculiar anatomic and hemodynamic factors. In addition, the LMCA segment is the least reproducible of all coronary segments with the largest reported intraobserver and interobserver variabilities.31–33 Therefore, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is often used to assess the severity of LMCA stenosis.

The significance of the stenosis at the LMCA necessitating revascularization should be determined by the absolute luminal area, not by the degree of plaque burden or area stenosis. Because of remodeling, a larger plaque burden can exist in the absence of lumen compromise.34 Abizaid et al reported the results of 1-year follow-up in 122 patients with LMCA stenosis. The minimal lumen diameter by IVUS was the most important predictor of cardiac events, with a 1-year event rate of 14% in patients with a minimal luminal diameter less than 3 mm.35 Fassa et al reported that the long-term outcomes of patients with LMCA stenosis with a minimal lumen area less than 7.5 mm2 who did not have revascularization were considerably worse than the outcomes of patients who were revascularized.36 Practically, it is important to keep the IVUS catheter coaxial with the LMCA and to disengage the guiding catheter from the ostium so that the guiding catheter is not mistaken for a calcific lesion with a lumen dimension equal to the inner lumen of the guiding catheter. When assessing distal LMCA disease, it is important to begin imaging in the most coaxial branch vessel from both branches. Nevertheless, distribution of plaque in the distal LMCA is not always uniform; and it may be necessary to image from more than one branch back into the LMCA.37,38 FFR may play an adjunctive role in determining significant stenosis at the LMCA. Fractional flow reserve is the ratio of the maximal blood flow achievable in a stenotic vessel to the normal maximal flow in the same vessel.39 A value of fractional flow reserve less than 0.8 is considered a reliable indicator of significant stenosis producing inducible ischemia. In patients with an angiographically equivocal LMCA stenosis, a strategy of revascularization versus medical therapy based on FFR cut-off point of 0.75 was associated with an excellent survival and freedom from events for up to 3 years of follow-up.40 On the basis of the results of IVUS and FFR, LMCA with IVUS area less than 6 mm2 or FFR less than 0.80 is generally considered a significant stenosis necessitating revascularization with CABG or PCI.

Outcomes of Drug-Eluting Stents Compared with Bare Metal Stents

Outcomes of Drug-Eluting Stents Compared with Bare Metal Stents

Safety in Terms of the Risk of Death, Myocardial Infarction, or Stent Thrombosis

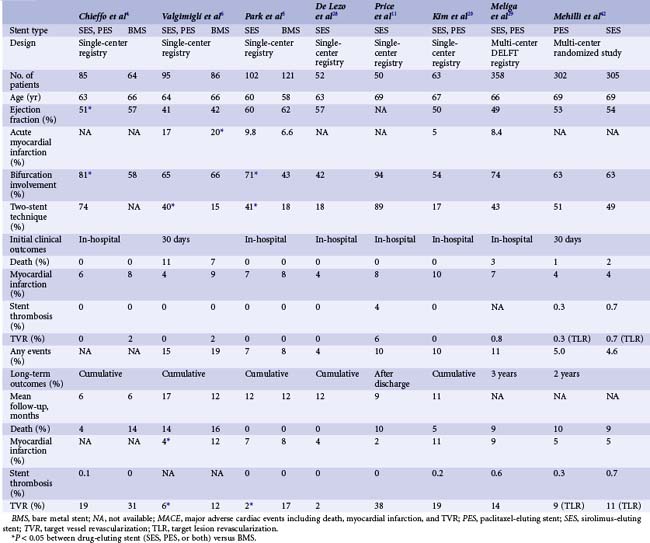

Although there are disputes about the long-term safety of DESs, the possibility of late or very late thrombosis has still been the major factor limiting global use of DESs, especially for unprotected LMCA stenosis. Table 22-1 depicts the results of recent studies demonstrating the outcomes of DES implantation for unprotected LMCA stenosis. It is clear that none of the clinical studies showed a significant increase in the cumulative rates of death or MI in DES implantation for unprotected LMCA, compared with BMS implantation. In the three early pilot studies comparing the outcomes of DESs with those of BMSs, the incidences of death, MI, or stent thrombosis were comparable in the two stent types during the procedure and at follow-up.4–6 Of interest, in the study by Valgimigli et al, DESs were associated with significant reduction in both the rate of MI (hazard ratio [HR] 0.22, P = 0.006) and composite of death or MI (HR 0.26, P = 0.004) compared with BMSs.6 Considering that re-stenosis can lead to AMI in 3.5% to 19.4% of patients, a significant reduction of re-stenosis achieved by DESs might contribute to the better outcome of DESs. In fact, a previous study warned that the episode of re-stenosis with the use of BMSs in LMCA stenosis could present as late mortality.41 In addition, more frequent repeat revascularization to treat BMS re-stenosis, in which CABG is the standard of care for unprotected LMCA, may also be related to the increase in hazardous accidents compared with DESs. A recent meta-analysis supported the safety of DESs by postulating that DESs did not increase the risk of death, MI, or stent thrombosis compared with BMSs.18 In this meta-analysis including 1278 patients with unprotected LMCA stenosis, for a median of 10 months, mortality rate in DES-based PCI was only 5.5% (range 3.4%–7.7%) and was not higher than BMS-based PCI. Recently, three registry studies assessed the risk of safety outcomes with the use of DESs compared with BMSs over 2 years.25–27 After rigorous adjustment using the propensity score or the inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting method to avoid selection bias, which was an inherent limitation of registry study, DES was at least not associated with long-term increase of death or MI. Of interest, the report of Palmerini et al showed the survival benefit of DESs over 2 years. These studies supported previous pilot studies that elective PCI with DES for unprotected LMCA stenosis seems to be a safe alternative to CABG. With regard to the risk of stent thrombosis, in the series of DES studies for LMCA stenosis, the incidence of stent thrombosis at 1 year ranged from 0% to 4% and was not statistically different from that with BMS.4–6 Recently, a multi-center study confirmed this finding that the incidence of definite stent thrombosis at 2 years was only 0.5% in 731 patients treated with DESs.19 In addition, the DELFT (Drug Eluting stent for LeFT main) multi-center registry, which included 358 patients undergoing LMCA stenting with DES, reported that the incidence of definite, probable, and possible stent thrombosis was 0.6%, 1.1%, and 4.4%, respectively, at 3 years.29 In recent multi-center large studies for the ISAR-LEFT-MAIN (Intracoronary Stenting and Angiographic Results: Drug-Eluting Stents for Unprotected Coronary Left Main Lesions) study or the MAIN-COMPARE (COMparison of Percutaneous Coronary Angioplasty Versus Surgical Revascularization) study, the incidence of definite or probable stent thrombosis was less than 1%.21,42 However, because these studies are still underpowered to completely exclude the possibility of increased risk of stent thrombosis in the very long term, further research needs to be performed with such a specific focus. Previous studies assessing the long-term outcomes of DESs for complex lesions showed slightly inhomogeneous outcomes. For example, recent large registries evaluating the safety of DESs for complex lesions showed comparable risks of death or MI for the two stent types.43,44 The recent large NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) registry in the United States reported that the off-label use of DESs, compared with BMSs, for similar indications was associated with a comparable 1-year risk of death and a lower 1-year risk of MI after adjustment.43 Of interest, a large registry that included 13,353 patients in Ontario (Canada) found that the 3-year mortality rate in a propensity-matched population was significantly higher with BMSs than with DESs.44 The comparable or lower incidence of death or MI with the use of DESs compared with BMSs, may be attributed, at least in part, to the off-setting risks of re-stenosis versus stent thrombosis.

Prognostic Factors

Several attempts have been made to predict the long-term outcomes of complex LMCA intervention. Predictably, peri-procedural and long-term mortality rates depend strongly on clinical presentation. In the ULTIMA (Unprotected Left Main Trunk Investigation Multicenter Assessment) multi-center registry, which included 279 patients treated with BMSs, 46% of whom were inoperable or high surgical risk, the in-hospital mortality was 13.7%, and the 1-year incidence of all-cause mortality was 24.2%.45 However, in the 32% of patients with low surgical risk (age <65 years and ejection fraction [EF] >30%), there were no peri-procedural deaths, and the 1-year mortality was 3.4%. Similarly, in DES implantation, high surgical risk represented by high EuroSCORE or Parsonnet score, was the independent predictor of death or MI.13,46 Therefore, it is recommended that a lot of attention should continue to be paid in the procedure of patients at high surgical risk. More recently, the SYNTAX (Synergy between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery) score, which is an angiographic risk stratification model, has been created to predict long-term outcomes after coronary revascularization with either PCI or CABG.47 In the recent SYNTAX study comparing PCI with paclitaxel-eluting stents (PESs) versus CABG for multi-vessel or LMCA disease, the long-term mortality was significantly associated with the SYNTAX score.47 Therefore, for patients with high clinical risk profiles or complex lesion morphologies, who are defined using these risk stratification models, the PCI procedures need to be performed by experienced interventionalists with the aid of IVUS, mechanical hemodynamic support, and optimal adjunctive pharmacotherapies, after a judicious selection of patients.

Recurrent Revascularization

Compared with BMSs, DESs reduce the incidence of angiographic re-stenosis and subsequently the need of repeat revascularization in unprotected LMCA stenosis. In early pilot studies, the 1-year incidence of repeat revascularization in DES implantation was 2% to 19% compared with 12% to 31% in BMS implantation (see Table 22-1).4–6 Fortunately, in a 3-year long-term study, the incidence of repeat revascularization remained steady, and, significantly, the “late catch-up” phenomenon of late re-stenosis was not noted after coronary brachytherapy.21 Two recent larger registries confirmed the efficacy of DESs.25,27 The risk of target lesion revascularization over 3 years was reduced by 60% with use of DES.27 The risk of re-stenosis was significantly influenced by lesion location. DES treatment for ostial and shaft LMCA lesions had a very low incidence of angiographic or clinical re-stenosis.14 In a study that included 144 patients with ostial or shaft stenosis in three cardiac centers, angiographic re-stenosis and target vessel revascularization (TVR) at 1 year occurred in only 1 (1%) and 2 (1%) patients, respectively. In contrast, PCI for LMCA bifurcation has been more challenging, although the prevalence had been more than 60% across previous studies.4–6,10,21 However, repeat revascularization was exclusively performed in patients with PCI for bifurcation stenosis.4–6 A recent study assessing the outcomes of DESs for LMCA stenosis showed that the risk of target vessel revascularization was six fold in bifurcation stenosis compared with nonbifurcation stenosis (13% vs. 3%).13 The risk of bifurcation stenosis was mostly highlighted in a recent study by Price et al who reported that the target lesion revascularization (TLR) rate after sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) implantation was 44%.11 In this study, 94% of patients (47 of 50) had lesions at the bifurcation and 98% underwent serial angiographic follow-up at 3 months, 9 months, or at both time points. This discouraging result cautioned against the efficacy of DESs and emphasized the need for meticulous surveillance with angiographic follow-up after PCI for LMCA bifurcation stenosis. However, this study was limited by the exclusive use of a complex stenting strategy (two stents in both branches) in 84% of patients, which might have increased the need of repeat revascularization. Although there was a debate about this, a current report proposed that the complex stenting technique might be associated with high occurrence of re-stenosis compared with the simple stenting technique.8,48 A subgroup analysis of the large Italian registry supported this with the hypothesis that a single-stenting strategy for bifurcation LMCA lesions had long-term outcomes comparable with that for nonbifurcation lesions.24 Taken together, before the novel treatment strategy is established, the simple stenting approach (LMCA to left anterior descending [LAD] artery with optional treatment in the left circumflex [LCx] artery) is primarily recommended in patients with relatively patent or diminutive LCx. Furthermore, future stent platforms specifically designed for LMCA bifurcation lesions may provide better scaffolding and more uniform drug delivery to the bifurcation LMCA stenosis. With regard to the differential benefit of DES type for the prevention of re-stenosis, the two most widely applicable DESs—SESs and PESs—had been evaluated in earlier studies. In an early study comparing the two DESs from a RESEARCH registry showed a comparable incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) with 25% in SESs (55 patients) and 29% in PESs (55 patients).12 The recent ISAR-LEFT-MAIN study with a prospective randomized design compared 305 patients receiving SESs and 302 patients receiving PESs.42 At 1 year, MACEs occurred in 13.6% of the SES group and 15.8% of the SES group with 16% and 19.4% of re-stenosis, respectively (P = NS). The subgroup analysis of MAIN-COMPARE registry supported the comparable safety and effectiveness of the two DESs.49 Use of a second-generation DES is being evaluated in many research studies.

Technical Issues of Left Main Stenting

Stenting Techniques

Stenting for ostial or body LMCA lesions seems very simple as the other stenting technique for non-LMCA coronary lesions. For instance, a brief and enough stent expansion is required to get optimal stent expansion and to avoid ischemic complications. In an ostial LMCA lesion, the coronary stent is generally positioned outside of the LMCA for complete lesion coverage of the ostium. Stenting for bifurcation LMCA lesions, however, is technically demanding and should be performed by experienced operators. In general, selection of the appropriate stenting strategy is dependent on the plaque configuration surrounding the LMCA. However, in spite of recent randomized studies comparing single-stent treatment versus two-stent treatment for bifurcation coronary lesions, the optimal stenting strategy for LMCA bifurcation lesions has not been determined yet.50,51 The current consensus is that the two-stent strategy does not have long-term advantages in terms of the incidence of any MACE compared with the single-stent strategy. Therefore, a systemic treatment of two-stent strategy for all LMCA bifurcation lesions—such as T stenting, kissing stenting, crush technique, or culotte technique—is not generally recommended. Instead, provisional stenting should be considered as the first-line treatment for LMCA bifurcations without significant side branch (SB) stenosis. Table 22-2 summarizes favorable and unfavorable angiographic morphologies toward single-stent and two-stent techniques for LMCA bifurcation stenosis. Fig. 22-1 is an example of a patient treated with provisional stenting, in which a single stent was placed in the LMCA crossing the LCx artery. However, as shown in Fig. 22-2, a patient with bifurcation LMCA disease involving the ostia of the LCx artery and the LAD arteries was treated with an elective two-stent technique.

TABLE 22-2 Favorable or Unfavorable Anatomic Features for Provisional Stenting in the Treatment of Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery Stenosis

| Anatomic Features | |

|---|---|

| Favorable | Significant stenosis at the ostial LCx artery with Medina classification 1.1.0. or 1.0.0. |