15 Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

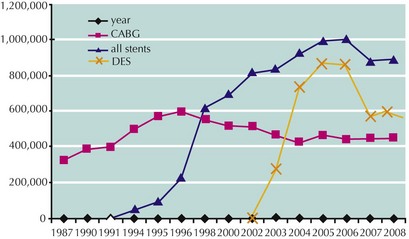

In the early 1990s, the introduction of coronary stenting revolutionized percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Short-term procedural results improved, and the incidence of emergency coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), at 3% to 5% in the 1980s, declined significantly to less than 1%. With the development of drug-eluting stents in the 2000s, the frequency of late repeat revascularization was reduced from 15% to 20% with bare-metal stents to 5% to 7% with drug-eluting stents. As a result of these improvements, and expanded indications for PCI, the number of PCI procedures has increased dramatically and the frequency of CABGs has been reduced (Fig. 15-1).

Performance of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Procedure and Equipment

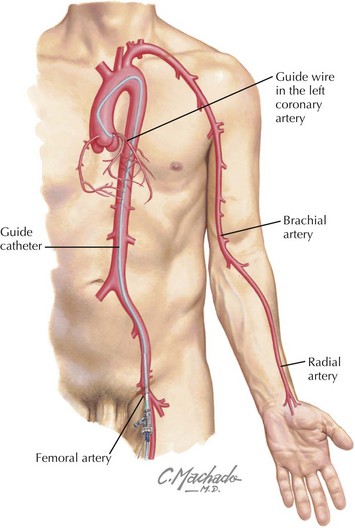

PCI is performed in cardiac catheterization laboratories with the same radiographic equipment used for diagnostic coronary arteriography. Arterial access is obtained via the femoral, radial, or brachial artery (Fig. 15-2). The femoral approach is used most frequently and is the preferred method taught at most training centers. The radial approach, which has the advantage of infrequent access site bleeding complications and reduced patient morbidity due to earlier ambulation after PCI, has gained popularity in recent years. Disadvantages of the transradial approach are the significant learning curve and the potential for radial artery occlusion. The presence of a patent ulnar artery and intact palmar arch (which can be assessed by physical examination) is a prerequisite for the use of this approach and provides assurance that should radial artery occlusion occur, it will be asymptomatic.

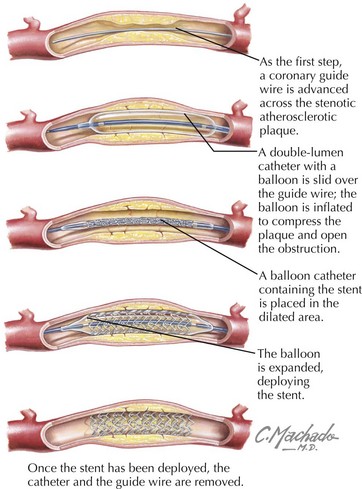

Interventional guide catheters are slightly larger than diagnostic catheters so as to accommodate balloons, stents, and other devices. After visualization of the coronary artery and target lesion via arteriography, a coronary guide wire is advanced across the lesion and positioned in the distal vessel. A small double-lumen catheter with a distal balloon is passed over the guide wire and positioned at the lesion. An inflation device is used to expand the balloon and open the obstruction by fracturing and compressing plaque. Today, coronary stenting is an integral part of virtually all angioplasty procedures. The undeployed stent is mounted on a second balloon catheter that is passed over the guide wire to the area initially dilated. Balloon inflation expands and deploys the stent (Fig. 15-3). A high-pressure balloon catheter is then used to fully expand the stent. With continued improvements in devices it is increasingly common to insert and fully expand the stent using a single-balloon catheter without predilatation.

Adjunctive Pharmacologic Therapy

A major problem with stent use has been thrombus formation on unendothelialized struts. The process of endothelialization is significantly inhibited with drug-eluting stents, and it may take months for struts to become completely covered. Late stent thrombosis (LST) occurring as long as a year after drug-eluting stent deployment is a major concern with currently available devices. Because of this concern, an oral antiplatelet program of aspirin and clopidogrel should be continued for 1 year after drug-eluting stent implantation to minimize this risk. Concerns about LST and potential bleeding complications from long-term dual antiplatelet therapy have tempered the early enthusiasm for the use of drug-eluting stents (see Fig. 15-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree