53 Percutaneous Balloon Pericardiotomy for Patients with Pericardial Effusion and Tamponade

Pericardial Effusion and Tamponade

Pericardial Effusion and Tamponade

The normal pericardium is a fibroelastic sac composed of visceral and parietal layers separated by a thin layer (20–50 mL) of straw-colored fluid.1 The normal pericardium has a steep pressure-volume curve: it is distensible when the intrapericardial volume is small but becomes gradually inextensible when the volume increases.1 In the presence of pericardial effusion, the intrapericardial pressure depends on the relationship between the absolute volume of the effusion, speed of fluid accumulation, and pericardial elasticity. The clinical presentation is thus related not only to the size of the effusion but also and more importantly to the rapidity of fluid accumulation. Pericardial effusion may result from a variety of clinical conditions (Table 53-1). Among medical patients, malignant disease is the most common cause of pericardial effusion with tamponade.1,2 Pericardial tamponade is a clinical syndrome with defined hemodynamic and echocardiographic abnormalities that result from the accumulation of intrapericardial fluid and impairment of ventricular diastolic filling.1,3 The ultimate mechanism of hemodynamic compromise is the compression of cardiac chambers secondary to increased intrapericardial pressure. In all cases of cardiac tamponade, the initial treatment consists of removing pericardial fluid by prompt pericardiocentesis and drainage. Reaccumulation of fluid with recurrence of cardiac tamponade may be an indication for a surgical intervention.1 Autopsy and surgical studies have shown that myocardial or pericardial metastases are found in approximately 50% of patients who present with cardiac tamponade due to malignancy.3–7 Although the short-term survival of patients with cardiac tamponade depends primarily on its early diagnosis and relief, long-term survival depends on the prognosis of the primary illness regardless of the intervention performed.4,5,8

TABLE 53-1 Etiology of Pericardial Effusion and/or Tamponade

| Idiopathic |

| Infectious |

| Viral |

| Bacterial |

| Fungal |

| Others |

| Metabolic |

| Uremia |

| Myxedema |

| Collagen and other autoimmune disorders |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Rheumatic fever |

| Dressler syndrome |

| Others |

| Neoplastic |

| Primary |

| Pericardial metastasis |

| Local invasion |

| Volume overload |

| Chronic heart failure |

| Miscellaneous |

| Chest wall irradiation |

| Cardiotomy or thoracic surgery |

| Adverse drug reaction |

| Aortic dissection |

| Post-myocardial infarction |

| Trauma |

From Jneid H, Maree AO, Palacios IF. Pericardial tamponade: clinical presentation, diagnosis and catheter-based therapies. In: J Parillo, PR Dellinger, eds. Critical Care Medicine. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Pericardiocentesis

Pericardiocentesis

Indications

Pericardiocentesis is the technique of catheter-based aspiration of pericardial fluid.1,3 It serves as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality in patients with pericarditis with pericardial effusion, pericardial effusion with pericardial tamponade, and effusive-constrictive pericarditis. Many asymptomatic patients with large effusions do not require pericardiocentesis if they have no hemodynamic compromise, unless there is a diagnostic need for fluid analysis. In a prospective long-term follow-up of patients with large idiopathic chronic pericardial effusion, Sagrista-Sauleda and colleagues9 concluded that large idiopathic chronic pericardial effusions were usually well tolerated for long periods in most patients with severe tamponade; however, they could develop unexpectedly at any time. Although pericardiocentesis was effective in resolving these effusions, recurrences were common, prompting the authors to recommend referral of these patients for pericardiectomy when recurrence occurs.10 When cardiac tamponade occurs, the emergency drainage of pericardial fluid by pericardiocentesis is a lifesaving therapy in a patient who would otherwise develop pulseless electrical activity and cardiac arrest. When performed, pericardiocentesis should (1) relieve tamponade when present, (2) obtain fluid for appropriate analyses, and (3) assess hemodynamics before and after pericardial fluid evacuation to exclude effusive-constrictive pericardial effusion. Elective pericardiocentesis is contraindicated in patients receiving anticoagulation, in those with bleeding disorders or thrombocytopenia with platelet counts <50,000/µL, and in those with hemorrhagic pericardial tamponade complicating aortic dissection. Pericardiocentesis is also ill advised when the effusion is very small or loculated.1,3

Technique

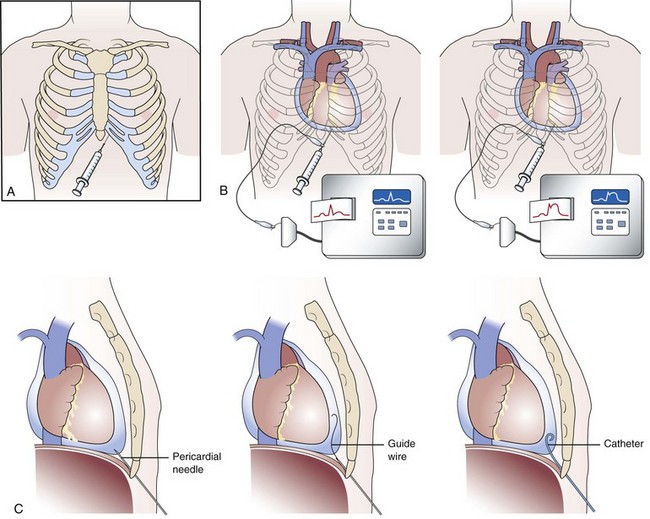

Pericardiocentesis is most commonly performed via a subxiphoid approach under ECG and fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 53-1A).3 Traditionally, pericardiocentesis has been performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory with arterial and right heart pressure monitoring.3 Today, however, the procedure is also performed in the noninvasive laboratory, intensive care unit, or even at bedside under echocardiographic guidance. Whichever modality is utilized, it is a safe procedure when performed by appropriately trained personnel. Pericardiocentesis is a procedure based on the Seldinger technique of percutaneous catheter insertion. After the administration of local anesthesia to the skin and deeper tissues of the left xiphocostal area, the pericardial needle is connected to an ECG lead. The needle is advanced from the left of the subxiphoid area while aiming toward the left shoulder (usually under fluoroscopic or echocardiographic guidance; however, blinded procedures can be undertaken during emergency procedures). Often, a discrete pop is felt as the needle enters the pericardial space. When ST-segment elevation is observed on the ECG lead tracing, it signifies that the needle has touched the epicardium and should be withdrawn slightly until the ST-segment elevation disappears (Fig. 53-1B). Once the pericardial space is entered, a stiff guidewire is introduced into the pericardial space through the needle, which is thereafter removed; then a catheter is inserted into the pericardial sac over the guidewire (Fig. 53-1C). The drainage catheter utilized usually has an end hole and multiple side holes. Intrapericardial pressure is measured by connecting a pressure transducer system to the intrapericardial catheter. Pericardial fluid is then removed, and samples of pericardial fluid are sent for appropriate biochemical, cytological, bacteriological, and immunological analyses for diagnostic purposes (the first sample is usually reserved for microbiological studies). In the presence of pericardial tamponade, aspiration of fluid should be continued until clinical and hemodynamic improvement occurs. The catheter is frequently left in place for continuous drainage and as a route to instill sclerosing or chemotherapeutic agents when needed. The catheter is secured to the skin using sterile sutures and covered with a sterile dressing. The success rate of pericardiocentesis is greater and the incidence of complications improves with the increasing size of the effusion.

Complications

The potential complications of pericardiocentesis include heart or a coronary vessel laceration, sometimes causing fatal consequences. Puncture of the right atrium or ventricle with hemopericardial fluid accumulation, arrhythmias, air embolism, pneumothorax, and puncture of the peritoneal cavity or abdominal viscera have all been reported. Acute pulmonary edema may infrequently occur when the pericardial tamponade is decompressed too rapidly. Other approaches of pericardiocentesis include the right xiphocostal, apical, right-sided, and parasternal approaches. Although these may be useful under certain circumstances, they are associated with a greater incidence of complications. The right xiphocostal approach is associated with higher incidence of right atrial and inferior vena cava injury. Puncture of the left pleura and the lingula is more frequent with the apical approach, while puncture of the left anterior descending and the internal mammary artery is more frequent with the parasternal approach. Echocardiographically-guided pericardiocentesis is a safe and effective technique. In a cohort of 1127 therapeutic echocardiography-guided pericardiocenteses performed in 977 patients at the Mayo Clinic (1979–1998), procedural success rate was 97% overall with a total complication rate of 4.7%.10 Echocardiography may be especially useful in patients with loculated effusions and unlike pericardiocenteses performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory the left chest wall is often utilized with echocardiographically-guided pericardiocenteses.

Postpericardiocentesis Management

Pericardiocentesis may not completely evacuate the effusion in most cases, given particularly that active secretion and bleeding into the pericardial space may continue.1,3 The pericardial catheter should therefore be left in place for 24 to 72 hours after the initial fluid evacuation until total daily drainage is ≤75 to 100 mL. The patient is admitted for continuous ECG monitoring and assessment of the rate of pericardial drainage. The pericardial space should be drained every 8 hours and the catheter flushed with heparinized saline and systemic antibiotics (usually first-generation cephalosporin for empirical coverage of gram-positive bacteria) are administered for the duration of the catheter stay. Based on the etiology of the effusion, the patient’s clinical and hemodynamic condition, and the amount drained, the pericardial catheter is usually removed within 72 hours and/or decisions for additional therapy are contemplated. Follow-up echocardiography is useful to monitor the resolution of the pericardial effusion and for signs of cardiac compression prior to catheter removal. Patients who continue to drain more than 75 to 100 mL/24 hr 3 days after standard catheter drainage should be considered for more aggressive therapy. Reaccumulation of the pericardial fluid is particularly common in patients with malignant pericardial effusions. Additional therapeutic approaches are available to prevent pericardial fluid reaccumulation. They include intrapericardial instillation of sclerosing agents, use of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, PBP, and surgical pericardial window. Reaccumulation of fluid with recurrence of cardiac tamponade is considered a definitive indication for a pericardial window.

Percutaneous Balloon Pericardiotomy

Percutaneous Balloon Pericardiotomy

The management of cardiac tamponade or large pericardial effusions at risk for progression to tamponade remains controversial and is dictated to a large extent by local institutional practices. Life-threatening cardiac tamponade requires immediate removal of pericardial fluid to relieve the hemodynamic compromise. Furthermore, it is desirable to prevent recurrence. For many patients with a pericardial effusion and tamponade, standard percutaneous pericardial drainage with an indwelling pericardial catheter is sufficient to avoid recurrence. Recurrences after catheter drainage have been reported in 14% to 50% of patients with pericardial effusion and tamponade.5,11–13 Patients who continue to drain more than 75 to 100 mL/24 hr 3 days after standard catheter drainage have been considered for more aggressive therapy. Several approaches are available to prevent reaccumulation of pericardial fluid, including intrapericardial instillation of sclerosing agents, use of chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.14,15 A surgically created pericardial window may provide an alternative for the treatment of pericardial effusions,16,17 but morbidity and late recurrence are not uncommon.8,18,19 The use of a subxiphoid surgical pericardial window has been advocated as primary therapy for malignant pericardial tamponade based on the high initial success in relieving tamponade18–23 and an acceptable recurrence rate.19 However, it is associated with high morbidity rates.8,16–23 Patients with advanced malignancy and cardiac tamponade are often poor candidates for surgical therapy. Because their life expectancy is already limited, the increased length of hospital stay associated with a surgical procedure may compromise the quality of their remaining lives. In addition, the malnutrition and chemotherapy associated with advanced malignancy increase the risk of infection and other perioperative complications. Therefore it is preferable to offer a less invasive alternative.

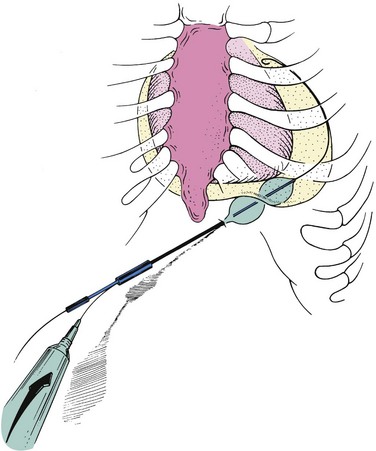

Palacios and colleagues24 proposed the technique of percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy (PBP) as a less invasive alternative to the surgical pericardial window procedure. With this technique, a pericardial window and adequate drainage of pericardial effusion can be done percutaneously with a balloon dilating catheter (Fig. 53-2). Since their initial report on 8 patients, the multicenter PBP registry investigators have reported data on >130 patients.25

Figure 53-2 Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy technique.

(From Ziskind AA, Pearce AC, Lemmon CC, et al. Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy for the treatment of cardiac tamponade and large pericardial effusions: description of technique and report of the first fifty cases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:1–5.)

Technique

The PBP technique is relatively simple and safe. It is performed in the catheterization laboratory with the patient under local anesthesia and mild sedation with intravenous narcotics and a short-acting benzodiazepine. There is minimal discomfort. Patients may be candidates for PBP if they have undergone prior pericardiocentesis and have persistent catheter drainage. Alternatively, PBP may be done as a primary therapy at the time of initial pericardiocentesis. For those who have previously undergone standard pericardiocentesis using the subxiphoid approach, a pigtail catheter has typically been left in the pericardial space for drainage. For patients who, after 3 days, continue to drain more than 75 to 100 mL/24 hr, PBP is offered as an alternative to a surgical procedure. The subxiphoid area around the indwelling pigtail pericardial catheter is infiltrated with 1% lidocaine. A 0.038-in. guidewire with a preshaped curve at the tip is advanced through the pigtail catheter into the pericardial space (Fig. 53-3A). The catheter is then removed, leaving the guidewire in the pericardial space. The location of the wire should be confirmed by its looping within the pericardium. After predilation along the track of the wire with a 10-Fr dilator, a 20-mm-diameter 3-cm-long balloon dilating catheter (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) is advanced over the guidewire and positioned to straddle the parietal pericardium. Care should be taken to advance the proximal end of the balloon beyond the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Precise localization of the balloon is accomplished by gentle inflation to identify the waist at the pericardial margin. The balloon is inflated manually until the waist produced by the parietal pericardium disappears (Fig. 53-3B and C). If the pericardium is opposed to the chest wall, as indicated by failure of the proximal portion of the balloon to expand, a countertraction technique should be used in which the catheter is withdrawn slightly, then gently advanced while the skin and soft tissues are pulled manually in the opposite direction. This maneuver isolates the pericardium for dilation (Fig. 53-4). Fluoroscopic imaging using multiple views (preferably biplane fluoroscopy) is helpful to ensure correct positioning of the balloon, which should be straddling the parietal pericardium (Fig. 53-5). At the operator’s discretion, 5 to 10 mL of radiographic contrast material may be instilled into the pericardial space to help identify the pericardial margin. Two or three balloon inflations are then performed to ensure the creation of an adequate opening of the pericardium. Although transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography may provide additional guidance to some aspects of the procedure, it is our experience that the balloon cannot be imaged adequately with echocardiography to identify the waist at the site of the pericardial margin.26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree