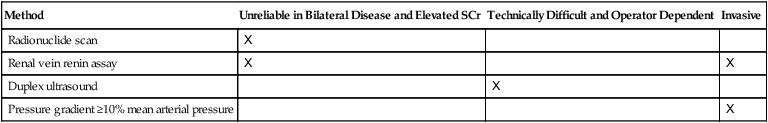

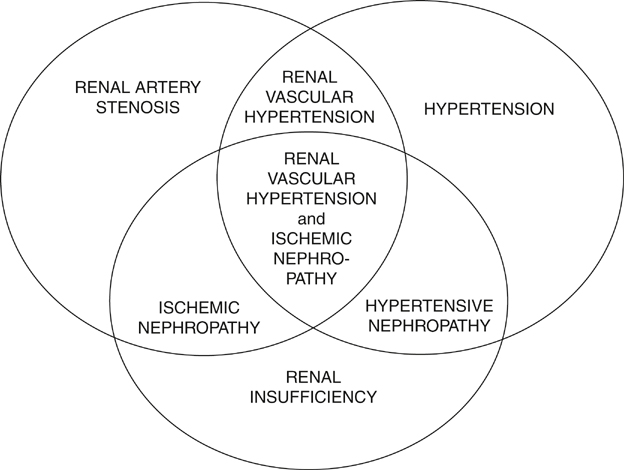

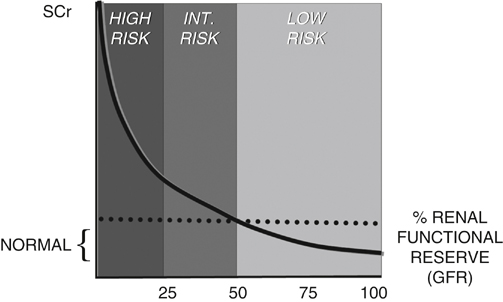

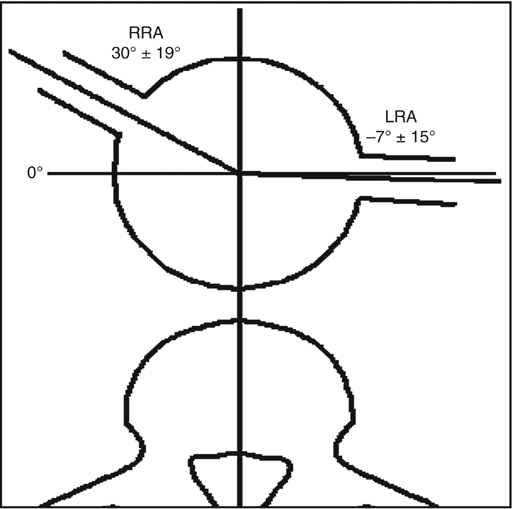

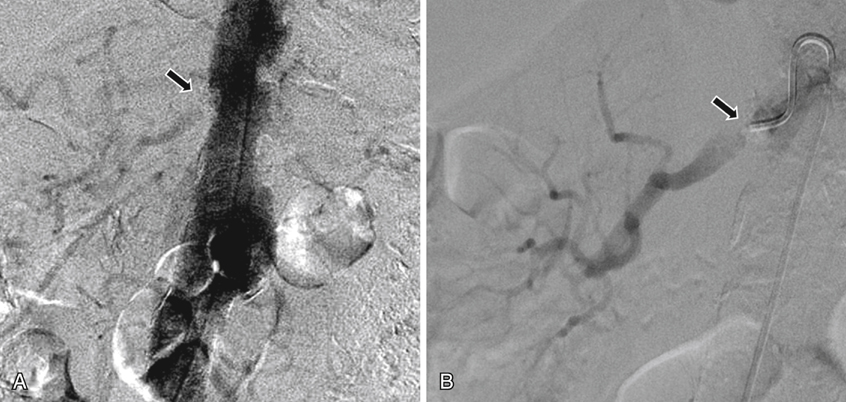

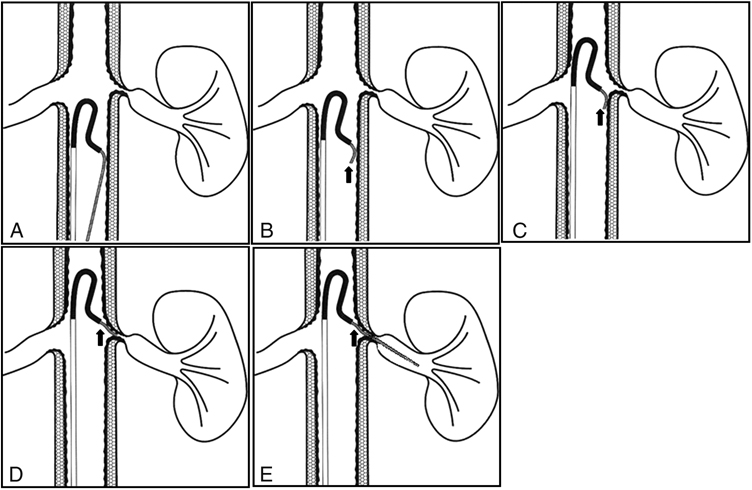

Hypertension, renal dysfunction, and atheromatous renal artery stenosis can occur independently or can be causally linked (Figure 1). There are unfortunately no foolproof and universally agreed upon criteria to identify patients in whom hemodynamically and physiologically significant anatomic renal artery stenosis is the cause of the clinical manifestations of potentially reversible ischemic nephropathy and renal vascular hypertension. A summary of the author’s selection criteria are shown in Boxes 1 and 2 and Table 1. TABLE 1 Physiologic Screening and Criteria for Diagnosis of Hemodynamically Significant Renal Artery Stenosis Almost all atheromatous renal artery stenoses occur at the aortic ostium. Extreme care must be taken during all catheter and wire manipulations in the juxtarenal abdominal aorta to minimize manipulations and iodinated contrast use to decrease the chances of microcholesterol embolization or contrast-induced nephropathy. As suggested by logarithmic glomerular filtration rate (GFR) curves (Figure 2), the likelihood of deterioration of kidney function following an equal insult during renal artery stenting is related to the preprocedure kidney function. The author advocates performing the procedure in the obliquity where the lesion is best seen on prior imaging and where the catheter tip is en face to the stenosis (Figures 3 to 5). The Sos flick technique (Figure 6) is used with the Sos Omni Selective (AngioDynamics, Queensbury, NY) recurve-type catheter and a soft-tipped Bentson-type wire for approaching and crossing renal artery stenoses. The Sos flick usually results in renal artery entry on one pass and almost never requires contrast injection. The author only 10 mL of half or third dilution of full-strength low-osmolar iodinated contrast by saline for aortography (Figures 6 and 7) and prehydrate patients before renal artery stenting, especially those with preexisting renal insufficiency or those at high risk for it. The evidence for using renal artery protection devices is lacking. They all are potentially dangerous and, most importantly, most cholesterol embolization has already occurred by extended fishing in the diseased juxtarenal aorta. In contrast to the STAR and ASTRAL trials, Patient A presented with clinically, anatomically, and hemodynamically (physiologically) significant renal artery stenosis and the serious clinical sequelae of chronic renal insufficiency as a result of ischemic nephropathy and renovascular hypertension. This patient was 84 years old and had an at least 10-year history of hypertension that had recently become uncontrolled (239/99 mm Hg) on three medications. On five antihypertensive medications BP was 160–180/60–70 mm Hg. She had a 10-year history of Sjögren’s syndrome and progressive chronic renal insufficiency (serum creatinine [SCr] increased from 1.5 mg/dL to 2.7 mg/dL over the previous 6 months). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) with gadolinium (see Figure 5) was performed, recognizing that there was a slight risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. MRA demonstrated severe bilateral ostial renal artery stenosis, left renal atrophy, and severe aortic atheroma in the region of the renal arteries. Aortography, selective right renal arteriography, and pressure gradient measurement confirmed these findings and the hemodynamic significance of the right renal artery stenosis. The patient in this case had many of the most important criteria for intervention outlined in BOX 3. Several treatment options are available including medical therapy, surgical revascularization, and percutaneous stenting. In this case, she had already clearly failed medical therapy. For surgical revascularization, hepatorenal bypass is an extra-anatomic reconstruction that has little risk of cholesterol embolization, but the patient had a moderately high anesthesia and surgical risk as a result of her age, diffuse vascular disease, and Sjögren’s syndrome. For percutaneous stenting, the irregular atheroma of the aortic wall and the intraluminal atheroma increased the chances of cholesterol embolization to 3% to 5%, but there was a low technical procedural and sedation risk.

Percutaneous Arterial Dilation and Stenting for Arteriosclerotic Renovascular Hypertension and Ischemic Nephropathy

Patient Selection

Method

Unreliable in Bilateral Disease and Elevated SCr

Technically Difficult and Operator Dependent

Invasive

Radionuclide scan

X

Renal vein renin assay

X

X

Duplex ultrasound

X

Pressure gradient ≥10% mean arterial pressure

X

Techniques of Renal Artery Stenting

Illustrative Case