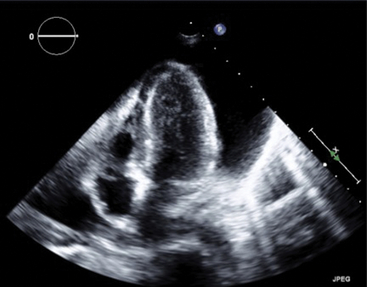

Chapter 15 The management of chronic pericardial effusions by cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons poses significant challenges and is burdened with limitations because of the generally moribund state of patients stricken with this condition. Malignancy and infection most commonly cause pericardial effusions in developed countries representing 23% and 27% of cases, respectively.1 In the case of malignant pericardial effusions, recurrence rates after pericardiocentesis range from 13% to 50%.2–4 Likewise, recurrence risk after subxiphoid pericardial windowing is nearly 5%. Neither treatment has been shown to reduce mortality rates, and, in the setting of advanced malignancy with associated malnourished and immunocompromised states, surgical windows pose significant perioperative risks including infection and prolonged hospitalization.5 Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy (PBP) was initially described by Palacios and colleagues in 1991.6 They presented their experience and technique in eight patients, all of whom were hospitalized with recurrent, malignant pericardial effusions after initial pericardiocentesis had been performed to relieve cardiac tamponade. In a subsequent multicenter registry of 50 patients, a 92% success rate with PBP in treating malignant pericardial effusions was reported.7 The technique has since evolved to include a double-balloon technique and the use of an Inoue balloon.8,9 Although the predominant experience with PBP has involved recurrent, malignant pericardial effusions, the procedure has also been successfully performed in cases of cardiac tamponade that occurred as a result of purulent effusions, pulmonary hypertension, uremic pericarditis, and congenital heart disease.10–13 The procedure can be considered in most cases of recurrent pericardial effusion after initial diagnostic and therapeutic pericardiocentesis. However, the majority of practice has been limited to cases of recurrent, malignant pericardial effusions. Although PBP has been performed on effusions of alternative etiologies,10–13 caution should be exercised in infectious etiologies, because PBP may lead to the development of an empyema. Both the patient and family also need to understand the grave nature of the patient’s condition, because the procedure is usually palliative. 1. Informed consent: Explain possible complications, including a pain and management plan, as well as potential damage to coronary arteries, atrial or ventricular perforation, pneumothorax, infection, bleeding, need for emergency surgery, potential arrhythmias, and death. 2. Preprocedural laboratories: Tests for complete blood count, electrolytes and renal function (given potential contrast administration and possible uremia-induced platelet dysfunction), and coagulation parameters should all be assessed. 3. Prophylactic antibiotics: Antibiotic prophylaxis with either cephazolin or vancomycin is reasonable, because most patients are immunocompromised and antibiotics have been shown to reduce the incidence of postprocedural fevers.7 4. Sedation/pain management: Barring significant hemodynamic compromise, judicious use of analgesics and sedatives is required. Intravenous fentanyl and midazolam work well for moderate conscious sedation. Subcutaneous lidocaine (Xylocaine) should be administered in close proximity to the pericardium as well. In addition, if renal function is not compromised, intravenous ketorolac works well to reduce both pain and the associated inflammatory response to the procedure. 5. Imaging: Adjunctive transthoracic echocardiography to determine optimal viewing windows and to aid in confirming intrapericardial position of the initial access before PBP is strongly recommended. The procedure is best performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory with use of both echocardiographic and fluoroscopic guidance. Initially, transthoracic echocardiography should be used to assure the presence of a large, circumferential effusion that can be accessed from the subxiphoid approach (Figure 15–1). Loculated effusions are best managed surgically. The ideal window is one where fluid accumulation is greatest, the pericardium is closest to the chest wall, and proximity to structures between the chest wall and the pericardium (i.e., liver, spleen) is limited or completely avoided.

Percutaneous Approach to Pericardial Window

15.1 Background

15.2 Indications

15.3 Preoperative Evaluation and Checklist

15.4 Procedural Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine