Lifetime risk estimation for cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been proposed as a useful strategy to improve risk communication in the primary prevention setting. However, the perception of lifetime risk for CVD is unknown. We included 2,998 subjects from the Dallas Heart Study. Lifetime risk for developing CVD was classified as high (≥39%) versus low (<39%) according to risk factor burden as described in our previously published algorithm. Perception of lifetime risk for myocardial infarction was assessed by way of a 5-point scale. Baseline characteristics were compared across levels of perceived lifetime risk. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the association of participant characteristics with level of perceived lifetime risk for CVD and with correctness of perceptions. Of the 2,998 participants, 64.8% (n = 1,942) were classified as having high predicted lifetime risk for CVD. There was significant discordance between perceived and predicted lifetime risk. After multivariable adjustment, family history of premature myocardial infarction, high self-reported stress, and low perceived health were all strongly associated with high perceived lifetime risk (odds ratio [OR] 2.37, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.72 to 3.27; OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.66 to 2.83; and OR 2.71, 95% CI 2.09 to 3.53; respectively). However, the association between traditional CVD risk factors and high perceived lifetime risk was more modest. In conclusion, misperception of lifetime risk for CVD is common and frequently reflects the influence of factors other than traditional risk factor levels. These findings highlight the importance of effectively communicating the significance of traditional risk factors in determining the lifetime risk for CVD.

Although a majority of the population of the United States is at low risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the short term (10-year estimate), most of these subjects are actually at high risk for developing CVD during their remaining life span. Physicians have routinely used short-term CVD risk estimation in primary prevention to guide decisions to treat blood pressure and cholesterol levels and encourage therapeutic lifestyle changes for those at highest risk. However, short-term risk estimates have important limitations, classifying most adults aged <50 years and many women as having low risk regardless of risk factor burden. Therefore, national guidelines have recently encouraged the use of long-term or lifetime risk as an adjunct to short-term risk communication in the primary prevention setting. Previous studies have observed that knowledge of short-term risk has been associated with healthy lifestyle patterns and the effectiveness of cholesterol- and blood pressure–lowering therapy. However, little is known about the perception of lifetime risk for CVD in the general population. Therefore, we sought to determine the perception of lifetime risk for CVD by comparing Dallas Heart Study (DHS) participants’ perceived lifetime risk with their predicted lifetime risk for CVD using our previously published algorithm.

Methods

The DHS is a multiethnic population-based probability sample of adult residents of Dallas County ages 18 to 65 years enrolled from July 2000 to January 2002. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. In the initial home visit, 6,101 participants underwent extensive household interviews. A subset of 3,557 participants aged 30 to 65 years participated in a follow-up visit, providing fasting blood and urine specimens and serial blood pressure measurements. Details of the study design, including collection of medical history, blood pressure, anthropometric measurements, and laboratory measurements, have been described previously in detail. In the present study, we included 2,998 subjects who participated in the follow-up visit of the DHS after excluding participants with a self-report of previous myocardial infarction (MI) and/or stroke (n = 181), a nonfasting blood sample (n = 94), and those missing measured baseline covariates (n = 284).

Race and/or ethnicity and current smoking status were defined by self-report. Education level was used as a surrogate for socioeconomic status instead of income level because many participants declined to provide financial information. High education level was defined as college degree or higher. Body mass index was calculated from measured height and weight. Diabetes mellitus was defined by a fasting glucose of ≥126 mg/dl, nonfasting glucose of ≥200 mg/dl, or the use of glucose-lowering medications. Family history of premature MI was defined as a first-degree male relative with a heart attack at age <50 years or a first-degree female relative with a heart attack at age <55 years in survey responses. Levels of stress and perceived health were determined by self-report to the following survey items in the DHS: “On a scale of 1-5, how would you rate your stress level? (1 = No stress at all; 5 = Extremely high stress)” and “How would you say your general health is? (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor).” High perceived stress was defined as a score of 4 or 5; low perceived stress was defined as a score of 1 to 3. High perceived health was defined as excellent, very good, or good; low perceived health was defined as fair or poor. Perceived lifetime risk for CVD was measured using the participants’ response to the following question: “On a scale of 1-5, how likely is it that you will have a heart attack in your lifetime? (1 = Least likely, 5 = Most likely).”

We estimated predicted lifetime risk according to our previously published algorithm where we classified each participant into 1 of 5 mutually exclusive risk factor categories according to their level of measured traditional CVD risk factors: all optimal risk factors, ≥1 not optimal risk factor, ≥1 elevated risk factor, 1 major risk factor, or ≥2 major risk factors. Compared with subjects in the lowest 2 risk factor categories (i.e., all optimal or ≥1 not optimal risk factor), subjects in the top 3 risk factor categories (i.e., at least 1 elevated risk factor) represent a unique subset, with higher observed lifetime risks for CVD, the presence of at least 1 treatable risk factor, and a greater prevalence and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis. Therefore, in the present study we used this previously validated threshold to determine the predicted lifetime risk for CVD, classifying each subject as having either “low predicted lifetime risk” or “high predicted lifetime risk” ( Supplementary Table 1 ).

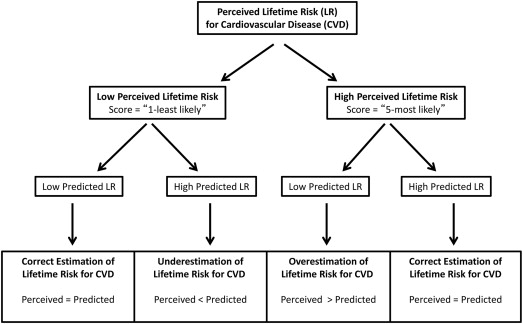

Because perceived lifetime risk was measured on a relative (i.e., “least likely” to “most likely”) rather than a quantitative scale, we studied further those subjects at the extremes of perceived lifetime risk. Therefore, those subjects who selected “5 (most likely)” were defined as having high perceived lifetime risk and those subjects who selected “1 (least likely)” were defined as having low perceived lifetime risk. We compared baseline characteristics across levels of perceived lifetime risk (1 [least likely] to 5 [most likely]) using linear trend tests and the Cochran-Armitage trend test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

To determine the independent association between risk factors and the perception of lifetime risk for CVD, we first constructed multivariate logistic regression models for all study participants to test the association between demographics, traditional CVD risk factors, and other personal characteristics and the perception of lifetime risk for MI, with high perceived lifetime risk (i.e., score = 5) as the outcome variable. To identify factors associated with correct or incorrect perception of lifetime risk of MI, we constructed multivariate logistic regression models separately for subjects with low predicted lifetime risk (i.e., all optimal or ≥1 not optimal risk factor) and for those with high predicted lifetime risk (i.e., at least 1 elevated risk factor). In both high and low predicted lifetime risk subgroups, incorrectly perceived lifetime risk was the outcome variable (i.e., perceived < predicted, and perceived > predicted) and correctly perceived lifetime risk was the referent (i.e., perceived = predicted). In participants with low predicted lifetime risk, we determined the association between participant characteristics and overestimation of lifetime risk for CVD (perceived > predicted). Similarly, in participants with high predicted lifetime risk, we determined the association between participant characteristics and underestimation of lifetime risk for CVD (perceived < predicted; Figure 1 )

All models were adjusted for age, gender, race, education level, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, current smoking, presence or absence of diabetes, presence or absence of family history of premature MI, and perceived levels of stress and health. These variables were selected in an effort to compare basic demographics, components of the Framingham and lifetime risk for CVD estimates, or because they were significantly different across levels of perceived lifetime risk. All reported p values are 2-sided at a significance level of 5%. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows (release 9.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Chi-square statistics were included to facilitate comparison of both categorical and continuous variables in determining risk perception.

Results

Most of the study participants had a high predicted lifetime risk for CVD. Of the 2,998 participants, 64.8% (n = 1,942) had a high predicted lifetime risk for CVD, whereas 35.2% (n = 1,056) had a low predicted lifetime risk for CVD ( Supplementary Table 1 ). The average perceived lifetime risk for CVD in the DHS was 2.6 on a scale from 1 (least likely) to 5 (most likely; Table 1 ). There was a significant discordance between perceived and predicted lifetime risk for CVD. For example, of 736 participants with the lowest perceived lifetime risk (score = 1, least likely), 42% had a high predicted lifetime risk and therefore appeared to underestimate their lifetime risk (perceived < predicted). Similarly, of 312 participants with the highest perceived lifetime risk (score = 5, most likely), about 1/2 (49%) actually had a low predicted lifetime risk and therefore overestimated their lifetime risk for CVD (perceived > predicted; Table 1 ). Factors associated with higher perceived lifetime risk for CVD were older age, traditional CVD risk factors, positive family history of premature MI, higher levels of perceived stress, and lower levels of perceived health ( Table 1 ).

| Variable | Least Likely | 2 (n = 772) | 3 (n = 806) | 4 (n = 372) | Most Likely | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 736) | 5 (n = 312) | |||||

| Age (years) | 42 ± 10 | 43 ± 10 | 44 ± 10 | 45 ± 9 | 44 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| Men | 339 (46%) | 317 (41%) | 363 (45%) | 175 (47%) | 128 (41%) | 0.665 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 464 (63%) | 340 (44%) | 347 (43%) | 167 (45%) | 162 (52%) | <0.0001 |

| White | 110 (15%) | 239 (31%) | 298 (37%) | 167 (45%) | 97 (31%) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 147 (20%) | 170 (22%) | 145 (18%) | 34 (9%) | 44 (14%) | <0.0001 |

| Other | 15 (2%) | 23 (3%) | 16 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 9 (3%) | 0.926 |

| Family history of premature MI | 52 (7%) | 62 (8%) | 73 (9%) | 56 (15%) | 66 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 123 ± 18 | 122 ± 17 | 124 ± 18 | 127 ± 18 | 127 ± 20 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 66 (9%) | 62 (8%) | 73 (9%) | 56 (15%) | 53 (17%) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 176 ± 38 | 180 ± 37 | 182 ± 38 | 184 ± 41 | 183 ± 46 | 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 30 ± 7 | 30 ± 8 | 30 ± 7 | 31 ± 7 | 32 ± 8 | 0.0002 |

| Current smoker | 191 (26%) | 178 (23%) | 234 (29%) | 130 (35%) | 100 (32%) | 0.0001 |

| Low predicted lifetime risk for CVD | 427 (58%) | 425 (55%) | 419 (52%) | 182 (49%) | 153 (49%) | 0.0002 |

| High predicted lifetime risk for CVD | 309 (42%) | 347 (45%) | 387 (48%) | 190 (51%) | 159 (51%) | 0.0002 |

| Stress level | ||||||

| None | 132 (18%) | 62 (8%) | 40 (5%) | 15 (4%) | 16 (5%) | <0.0001 |

| Extremely high | 44 (6%) | 46 (6%) | 73 (9%) | 45 (12%) | 69 (22%) | <0.0001 |

| Perceived health | ||||||

| Excellent | 162 (22%) | 100 (13%) | 81 (10%) | 26 (7%) | 19 (6%) | <0.0001 |

| Poor | 7 (1%) | 15 (2%) | 16 (2%) | 22 (6%) | 34 (11%) | <0.0001 |

| Education level | ||||||

| < High school | 179 (24%) | 153 (20%) | 128 (16%) | 51 (14%) | 74 (24%) | 0.013 |

| High school | 247 (34%) | 214 (28%) | 232 (29%) | 115 (31%) | 112 (36%) | 0.656 |

| Some college | 202 (27%) | 221 (29%) | 223 (28%) | 114 (31%) | 82 (26%) | 0.905 |

| College + | 107 (15%) | 184 (24%) | 223 (28%) | 92 (25%) | 44 (14%) | 0.078 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree