Pediatric Midabdominal Coarctation

SHIPRA ARYA and DAWN M. COLEMAN

Presentation

A 6-year-old male presents with elevated blood pressure following routine adenoidectomy. On physical examination, his systolic blood pressure measures 180 to 200 mm Hg and diastolic pressures measure 90 to 100 mm Hg in both arms; lower extremity pressures are approximately 95/55 mm Hg. He is admitted for hypertensive urgency and requires four antihypertensive agents for adequate blood pressure control. A vascular surgery consult is obtained. He has an abdominal bruit on auscultation. His bilateral femoral pulses and pedal pulses are nonpalpable, but present on Doppler exam.

Differential Diagnosis

Pediatric abdominal aortic coarctation or middle aortic syndrome (MAS) is an uncommon clinical condition generated by segmental narrowing of the abdominal or distal descending thoracic aorta. Coarctation can involve any portion of the aorta, but most commonly occurs distal to the ductus arteriosus. The abdominal aorta is affected in only 0.5% to 2% of aortic coarctations.

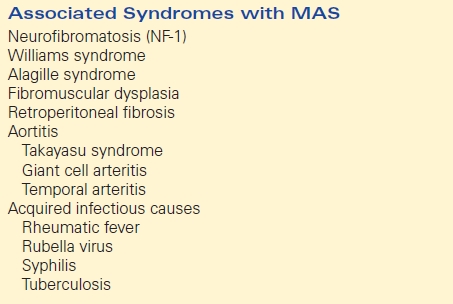

MAS may be acquired (associated with clinical syndromes referenced in Table 1) or congenital, ascribed to a developmental anomaly in the fusion and maturation of the paired embryonic dorsal aortas. Segmental aortic stenosis may be located at the suprarenal (69%), interrenal (23%), and infrarenal (8%) positions, with a high propensity for concomitant stenoses in both the renal (80%) and visceral (60%) arteries.

TABLE 1. Associated Clinical Syndromes

Hypertension proximal to the aortic stenosis, and relative hypotension distal to it, are characteristic findings in MAS, present in 94% of patients. Changes in pulsatile flow and pressure across renal stenoses or aortic narrowings are responsible for renin-angiotensin system activation and subsequent blood pressure elevations. This form of renovascular hypertension is typically resistant to simple pharmacologic control. Other manifestations including exercise-related lower extremity fatigue or visceral ischemia are less frequent, despite the majority of patients having differential upper and lower extremity blood pressures and associated splanchnic and renal arterial occlusive disease.

Differential diagnoses include essential hypertension, endocrine dysfunction, isolated renal artery stenosis, renal parenchymal disease, Wilms tumor, and neuroblastoma, among others. This patient’s medically refractory hypertension despite multiple antihypertensive agents, abdominal bruit, and lack of palpable femoral pulses suggests aortic coarctation.

Workup

Additional clinical history should elicit constitutional symptoms concerning for vasculitis, lower extremity and generalized fatigue with exertion, flank pain, hematuria, and relevant family and birth history. A thorough clinical exam should assess for features suggesting one of the aforementioned clinical syndromes (Table 1), abdominal mass, abdominal bruit, stature, and costal margin. Blood work should be sent to assess renal function (BUN, creatinine), vasculitis (C-reactive protein), and electrolyte levels. Additionally, blood hormone levels may help differentiate the diagnosis in cases of pediatric hypertension. Specifically, high plasma renin activity indicates renovascular hypertension (including MAS), while altered aldosterone and catecholamine levels may indicate endocrine dysfunction (i.e., hyperaldosteronism, pheochromocytoma) or neuroblastoma. Urinalysis will reveal hematuria, concerning for intrinsic renal disease. Fasting lipid panels and oral glucose tolerance tests should be considered to evaluate metabolic syndrome in obese children.

Ultrasonography should be considered the first-line diagnostic imaging modality in patients with renovascular hypertension. Transabdominal aortorenal duplex may reveal abdominal aortic coarctation and renal artery stenosis; additionally, abdominal ultrasonography may reveal tumors and structural anomalies of the kidneys and allow for assessment of renal size, symmetry, and the presence of renal scarring. Echocardiography should be performed to assess for left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and ventricular function in addition to surveillance of the thoracic aorta for coarctation. Cross-sectional imaging with computed tomography angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) will provide more specific anatomic information regarding aortic coarctation and any associated renal and visceral pathology. MRA is often favored in pediatric patients as it offers diagnostic sensitivity without the associated risks of irradiation. Arteriography with multiplanar and selective views is a helpful adjunct for preoperative planning to define the extent of the coarctation and renal/visceral arterial involvement. Additionally, angiography offers the specificity to identify additional smaller accessory renal arteries or segmental arterial stenoses that might otherwise be missed with traditional cross-sectional imaging. Finally, the adequacy of the iliac arteries for use as conduit can be assessed.

On clinical exam, this patient is of appropriate height and weight for age and has no stigmata concerning for associated syndrome. As referenced above, he has an abdominal bruit, no abdominal masses, and nonpalpable femoral and pedal pulses. Abdominal ultrasound with renal duplex revealed normal renal size, bilateral renal artery stenosis, and aortic narrowing. An echocardiogram revealed mild LVH with preserved function. MRA confirmed midabdominal aortic coarctation extending from the celiac artery to the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) with associated superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and bilateral renal artery stenoses (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1 Magnetic resonance angiography revealing midabdominal aortic stenosis and associated superior mesenteric and bilateral renal artery stenoses. (From Stanley JC, Criado E, Eliason JL, et al. Abdominal coarctation: surgical treatment of 53 patients with a thoracoabdominal bypass, patch aortoplasty, or interposition aortoaortic graft. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1073–1082.)

Diagnosis and Treatment

Untreated pediatric midabdominal coarctation may result in failure to thrive, hypertensive crisis, stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, renal atrophy, renal insufficiency, progressive LVH with associated heart failure, flash pulmonary edema, and decreased life expectancy (less than 40 years).

Indications for surgical revascularization include medically refractory hypertension (despite three drugs), progressive renal insufficiency, nonischemic cardiomyopathy resulting from concentric LVH, failure to thrive, and lower extremity sequelae (claudication, exertional fatigue, and/or growth disturbance). Often, despite dramatic clinical presentations, even patients with hypertensive emergencies can be managed appropriately medically once the diagnosis of renovascular hypertension secondary to MAS is confirmed. The timing of surgery is especially relevant in pediatric patients given projected axial and vascular growth postrepair and the technical challenges that encompass revascularization in the infant and toddler. As such, at the youthful extreme, it is prudent to allow for growth to at least 3 to 4 years of age is possible, even if this requires a dramatic medication regimen of five to six drugs.

Given this patient’s age of 6 years, medically refractory hypertension, and evidence of LVH, revascularization should be considered.

Surgical Approach

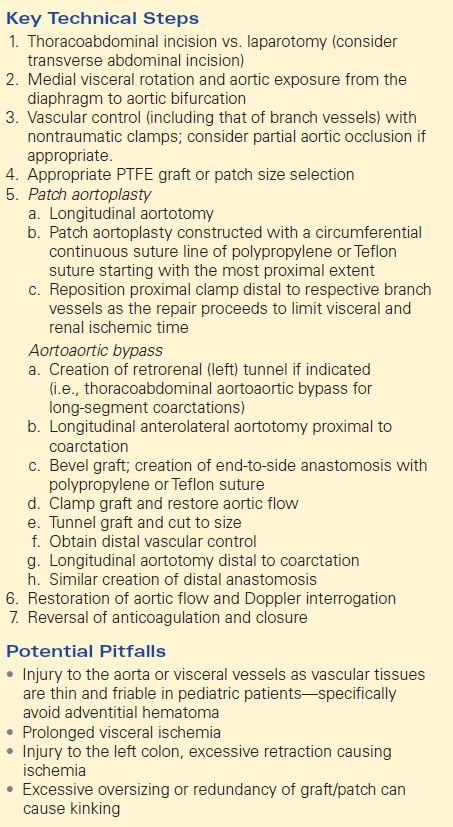

Open surgical repair is the primary treatment for abdominal aortic coarctation. Options for revascularization include aortoaortic bypass around the diseased segment, patch aortoplasty, and, less commonly, interposition grafting of the aortic segment. Revascularization of indicated renal artery or mesenteric stenosis should be performed concomitantly as indicated Table 2.

TABLE 2. Pediatric Aortic Reconstruction for Coarctation