Paul Grayburn did his general cardiology fellowship under the tutelage of Dr. Anthony N. DeMaria at the University of Kentucky from 1984 to 1986, followed by a year of interventional cardiology training with Dr. David C. Booth. In 1988, he was recruited to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School by Dr. James T. Willerson, where he served on the faculty for 15 years. During that time, he was director of the echocardiography laboratories at the University of Texas Southwestern and chief of cardiology at the Dallas Veterans Affairs Medical Center, where he also practiced interventional cardiology. In 2002, Dr. Grayburn moved to Baylor University Medical Center to accept the Paul J. Thomas Chair in Cardiology Research and Education. He has published more than 260 articles, mainly in peer-reviewed medical journals. He has served as an associate editor of The American Journal of Cardiology since 1997. He is on the editorial boards of Circulation , the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Imaging , and Heart . Dr. Grayburn currently serves on the Publications Committee for the Endovascular Edge-to-Edge Repair Study (EVEREST) II and the Core Lab Committee and Steering Committee of the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) trial. He has held a National Institutes of Health K24 grant for mentoring junior faculty members and an R01 grant, “Functional Mitral Regurgitation in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy,” for 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiographic evaluation of the mechanisms of functional mitral regurgitation (MR) in the STICH trial. He has served on multiple committees for the American Society of Echocardiography, including the Task Force for Quantitation of Valvular Regurgitation. He is currently the principal investigator for the MitraClip (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois) studies at Baylor Health Care System and co-investigator for the Cardiothoracic Surgery Network Trials on MR. Dr. Grayburn’s background in interventional cardiology and echocardiography, including intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography during surgical mitral valve repair, give him a unique insight into percutaneous mitral valve therapies.

William Clifford Roberts, MD (hereafter Roberts): Dr. Grayburn, I appreciate your coming to my house for our discussion. It is March 24, 2011. You have been involved with percutaneous mitral valve repair for a number of years?

Paul A. Grayburn, MD (hereafter Grayburn): Yes, since 2002.

Roberts: Let’s go back to the surgeon, Ottavio Alfieri. He was the one who initiated attaching the margins of both anterior and posterior leaflets together in the center of the orifice to reduce the degree of MR operatively. When did that start?

Grayburn: He first reported what is now known as the Alfieri operation in 1995.

Roberts: Paul, how did that procedure work out? He did quite a few cases himself, and a few other surgeons did a few cases but then they all quit doing them. Are long-term results available on that operative procedure?

Grayburn: The Alfieri repair technique is performed infrequently. It is occasionally used as a last-ditch attempt to salvage a mitral valve repair and avoid mitral valve replacement for degenerative MR. For repair of functional MR, particularly in ischemic cardiomyopathy, it’s usually not used, even though that is the group of patients for which Alfieri originally developed the technique. Alfieri’s more recent data suggest that the suture technique works best if an annuloplasty ring is also inserted. Most of us are disappointed with the results of mitral valve repair of functional MR due to a dilated left ventricle regardless of technique.

Roberts: When you say “functional MR,” you mean that the mitral valve leaflets and chordae are anatomically normal.

Grayburn: Exactly. Functional MR is thought to be a disease of the left ventricle.

Roberts: For the Alfieri procedure to work, not only does the figure-8 suture have to be utilized, but a mitral ring must be utilized as well. That was his conclusion?

Grayburn: Yes. Functional MR may be more complex. For example, not all patients with “functional” MR have a dilated annulus. In such patients, the Alfieri stitch might work well as a primary repair technique. Other patients have tenting of the leaflets towards the apex as the papillary muscles are pulled outward. Others have phenomenal discoordination of the ventricular septum and lateral wall, which may respond to a biventricular pacemaker. Some patients have combinations of these pathologies. Every patient with “functional” MR is a little bit different.

Roberts: When you say pulling of a mitral leaflet by the papillary muscles, that’s toward the apex such that the orifice is prevented from closing during ventricular systole because the ventricle has dilated both longitudinally and laterally?

Grayburn: Correct. That is known as the Carpentier class 3B mechanism for MR: restriction of leaflet closure.

Roberts: The percutaneous procedure for repairing or diminishing the quantity of MR started when and where?

Grayburn: I first got involved with it in November 2002, when I met with Jan Komtebedde, a veterinarian working for a company called Evalve, Inc. Evalve came up with a design for a metallic clip that could be placed percutaneously, pinning the anterior and posterior mitral leaflets together in the same manner as an Alfieri suture. Evalve developed the technique, and the device known as the MitraClip. The company recently has been purchased by Abbott Vascular.

Roberts: What does the device look like? Can you describe it?

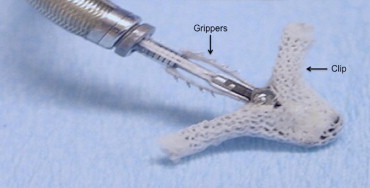

Grayburn: The clip itself is made of cobalt chromium, and it has a polyester covering on it ( Figure 1 ). It is delivered through a 24-inch sheath that tapers to 22Fr at the tip. It is inserted through a femoral vein and then advanced across the atrial septum. It has a steerable guide that allows one to orient the clip properly toward the mitral valve once the sheath is placed and the dilator removed. The clip is operated by a mechanism that sits outside the body.

Roberts: That’s after entering through the atrial septum?

Grayburn: Correct. The whole procedure has to be guided by transesophageal echo (TEE). The procedure involves a complex interplay between a skilled interventionalist and a skilled echocardiographer to identify the anatomy properly and to place the clip in the proper position.

Roberts: You started doing these at Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) when?

Grayburn: We did our first patient in 2006.

Roberts: How many have you done subsequently at BUMC?

Grayburn: We have now done 24 patients. We do them at both of the Baylor heart hospitals: downtown and at Plano.

Roberts: Has it been difficult to recruit these patients?

Grayburn: Yes and no. We get many referrals for the procedure. Of our last 112 patients referred for TEE to see if they are candidates for the clip, only 17 patients were eligible and received a clip. Many patients referred are excluded from the percutaneous procedure because their anatomy is not suitable for clip placement or they don’t have enough MR to require a clip.

Roberts: What are criteria presently for doing this percutaneous procedure?

Grayburn: A typical patient with mitral valve prolapse would require that the MR jet be at the A2-P2 interface, basically in the center of the mitral coaptation line.

Roberts: How many scallops are there in a normal mitral valve?

Grayburn: There are 3 scallops in the posterior leaflet. The anterior leaflet does not have any. In addition to requiring that the middle scallop of the posterior leaflet or the corresponding segment of the anterior leaflet be involved, the width of the flail segment cannot be >1.5 cm, and the difference between the flail gap , which is how far apart the leaflets are, cannot be >1.0 cm.

Roberts: The length of the leaflet is the distance from its attachment to the mitral annulus to the free margin?

Grayburn: If a segment is flail, that flail segment cannot be >1.5 cm wide, or the clip would not be able to restore the integrity of the valve. We look for a narrow flail segment.

Roberts: Are you looking at the length from the attachment of that leaflet to its free margin? You are not looking at the width of that leaflet according to its attachment to the mitral annulus?

Grayburn: We look at both. The term flail width is the width of the segment along the commissure line from commissure to commissure.

Roberts: That would correspond to the annular width.

Grayburn: The other measurement is the distance from the free edge of the anterior leaflet to the free edge of the posterior leaflet. If it is too far apart, both leaflets cannot be grabbed by the clip.

Roberts: The distance apart or gap has to be <1.1 cm.

Grayburn: Yes.

Roberts: That is in ventricular systole?

Grayburn: Correct.

Roberts: What is it normally in ventricular diastole?

Grayburn: In ventricular diastole, when the leaflets are fully opened, it could easily be 3 to 4 cm. But that distance is not relevant, because the clip is deployed in ventricular systole, when the leaflets are close together.

Roberts: How many patients have had this percutaneous procedure so far worldwide?

Grayburn: At the present time, >3,000 procedures have been done worldwide. The clip is approved in Europe, so it is much easier to get the clip there, and it is being done a lot more commonly in Germany and Italy and other places in Europe than in the USA, where its use is still restricted by the FDA (US Food and Drug Administration). In the USA, the clip can only be used as part of a continuing-access registry or compassionate-use protocol.

Roberts: What do you mean by “compassionate-use” protocol for this percutaneous procedure?

Grayburn: After the randomized trial was completed, the FDA allowed a continuing-access registry that goes under the name REALISM (Real World Expanded Multicenter Study of the MitraClip System). The FDA allows 20 patients per month to be done in the USA. This is a common practice of the FDA. Their point is to allow investigators who have acquired skill in doing this procedure to maintain those skills until such time as the device can be approved.

Roberts: That’s 240 procedures for the year in the entire USA?

Grayburn: Yes. More recently, the FDA has come out with a compassionate-use protocol so that certain patients who either are nonsurgical candidates or require an urgent or emergent use or just a use under a compassionate-care protocol are allowed. It’s difficult to get that done, because it requires a series of letters and approvals from the company and the FDA. Nevertheless, those patients can also be done at the present time.

Roberts: What patient with pure MR would you not consider for this procedure?

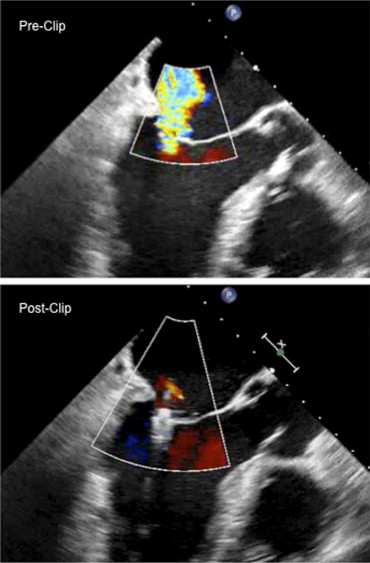

Grayburn: The results of the EVEREST II trial have just been published. This trial randomized patients with significant MR (3 to 4+) to the clip versus to surgery. Surgical repair was more effective at relieving MR, but the clip was safer than surgery. Surgery was more likely to end up with either no MR or only mild MR, whereas the clip more likely ended up with mild or moderate (1 to 2+ MR) ( Figure 2 ). The major safety difference was that there was a marked reduction in need for blood transfusion with the clip as compared to surgery. The trade-off is that surgery provides a better chance of complete elimination of the MR, particularly in patients with mitral valve prolapse, but obviously surgery is more invasive and less safe. Certain patients definitely should go to surgery. Those would include patients who have need for other valve surgery, or they need coronary bypass surgery or a maze operation for concomitant atrial fibrillation. For a young patient with posterior leaflet prolapse, the surgical results are both excellent and durable. Our first patient with the clip is doing well 5 years later. There are a couple of patients followed 8 years after the clip insertion. The long-term durability of the clip, however, has not been proved yet. Patients at high risk for surgery might be perfect candidates for the clip because of its much less invasive nature.

Roberts: Any degree of mitral stenosis would be a contraindication to percutaneous clip implantation?

Grayburn: Correct.

Roberts: One thing that Dr. Robert Bonow has stressed is that the average US cardiac surgeon, when a patient is sent for a mitral valve repair, has a greater chance of leaving the operating room with a mechanical prosthesis or bioprosthesis than a repair. The average cardiac surgeon is probably not very good at mitral valve repair for pure MR.

Grayburn: The STS (Society of Thoracic Surgeons) database, upon which those data are derived, does not allow discrimination of the mechanism of the MR. Of course, some mitral valve replacements are necessary because of an unsuitable valve for repair. For example, it could have been a prior repair that failed and now a replacement is required, and the valve could not and should not have been repaired. However, I agree that most US cardiac surgeons have a low volume of mitral valve repairs and probably are not experts at doing that operation.

Roberts: I understand that the average US surgeon does only about 10 valve operations a year. In EVEREST II, comparing mitral repair operatively to the percutaneous mitral clip, the surgeons involved have done a good number of mitral repairs.

Grayburn: That’s true. The quality of surgeons at the EVEREST II sites was very good, and they were selected specifically for having good operative results from mitral valve repair operations.

Roberts: How many sites were involved in EVEREST II?

Grayburn: There were 38 sites in the USA, although not all sites were particularly active.

Roberts: How many patients will be in the EVEREST II analysis?

Grayburn: The study was enrolled 279 patients: 184 randomized to the MitraClip and 95 to surgery. However, only 80 of the 95 patients randomized to surgery actually underwent surgery. Some patients randomized to surgery decided not to have it.

Roberts: Did they have the clip instead?

Grayburn: No, because they were randomized to surgery, they were supposed to have surgery, but something happened. Typically, they changed their minds.

Roberts: What about the patients randomized to the clip? Did any of them prove to be unsuitable for the clip?

Grayburn: Yes. Six patients randomized for the clip changed their minds.

Roberts: All of the patients in EVEREST II could have had either procedure?

Grayburn: Correct.

Roberts: The publication that appeared in JACC ( Journal of the American College of Cardiology ) on August 18, 2009, was an analysis of those patients who had the clip. There was no randomization in that study?

Grayburn: Yes. That was the EVEREST I study, which evaluated the safety and feasibility of the clip.

Roberts: The percutaneous clip procedure, I gather, is quite a long one, maybe 4 hours or so early on, about the same amount of time that the operative figure-of-8 edge-to-edge procedure takes. What is your experience at BUMC? How long does this percutaneous clip procedure take to do?

Grayburn: We are now doing almost all of the procedures in <2 hours. Both EVEREST I and EVEREST II trials were done while the investigators were on their learning curve of the clip. We’ve gotten better in several ways: (1) we are better at identifying who can and who cannot have a successful result with the clip, and (2) we are faster and more proficient at placing the clip.

Roberts: These studies are before you go to the operating room?

Grayburn: Yes. The preoperative study is to determine whether a clip is a good idea or not. That’s a part of the learning curve. There is another learning curve in the actual procedure. One thing we’ve learned is the actual site of the transseptal puncture is critical to being able to quickly and effectively deploy the clip. The atrial septum has to be punctured more posteriorly and superiorly than we normally do to give room to come down with the device in a coaxial manner on top of the mitral leaflets. Now, we spend a lot more time making sure we do the transseptal puncture correctly.

Roberts: If you have a circular foramen ovale membrane, you don’t try to hit it in the center or the top but as close to the bottom of that membrane as you can.

Grayburn: Right, we want to stay as far posterior as we can to stay away from the aorta and superior to the mitral leaflets. We’ve recently done 3 cases with a device time of <60 minutes. That’s not skin-to-skin but the time once the mitral valve clip is ready to be applied after the transseptal puncture. If the transseptal puncture is in the correct site the clip can be attached in both leaflets fairly quickly.

Roberts: You use the TEE during the procedure?

Grayburn: Yes.

Roberts: One person manipulates the echocardiogram, and the other person puts in the device. Can you go through the procedure step by step?

Grayburn: Sure. The patient is intubated in the lab by an anesthesiologist. The TEE probe is placed, and the mitral valve is again evaluated. Then the interventionalist puts in a venous sheath in a femoral vein. Early on, a full left-sided heart catheterization was done: ventriculogram and left atrial and left ventricular pressure measurements. Now few labs do a full left-heart catheterization. The first step is the transseptal puncture using a Brockenbrough needle under TEE guidance to make sure the location of the puncture is both superior and posterior. Then, a guidewire is placed in the left upper pulmonary vein and the transseptal system is removed. Then, the femoral vein is dilated to accommodate the large sheath. The MitraClip sheath system is then put in and advanced into the left atrium.

Roberts: How wide is the mitral clip system?

Grayburn: It is a 24Fr system which is 8 mm in diameter. The engineers will eventually, I suspect, make these instruments smaller. Once the sheath is placed, then the clip system is introduced into the sheath, being very careful to avoid any air bubbles.

Roberts: The sheath is about 8 mm in width?

Grayburn: Yes. The clip of course is smaller than 8 mm, so that it can go through the sheath. The guidewire is removed, and then the clip is introduced and advanced so that it is extending completely out of the sheath. This is done under TEE guidance to be sure that the tip of the clip is free in the left atrial cavity and not up against the wall, which could perforate. Once that clip is out of the sheath, we steer it down toward the mitral orifice. Medial-lateral and anterior-posterior steering is done to position the clip in the exact location of the MR jet. The clip is then opened, and its position is again checked to make sure it’s where it should be. We also make sure that the clip is oriented perpendicular to the coaptation line. Then the clip is advanced into the left ventricular cavity, simultaneously checking to make sure the clip has not rotated. If a clip is placed, for example, at a 45° angle to the closure line, the MR might actually be worsened. Thus, great care is taken during this time to make sure the alignment of the clip and position of the clip relative to the MR jet is perfect. Then the clip is pulled back under TEE guidance. We want the anterior and posterior mitral leaflets to drop down into the center of the clip, and then little grippers are lowered to pin those leaflets together. Then, the clip is tightened and closed so the leaflets are coapted. Again, we check carefully under TEE guidance that the leaflets are inserted completely down into the clip and that the grippers are on top of them so we have good grasping. The grippers almost look like Velcro where they come down from above and pin the leaflets between the clip and the gripper ( Figure 1 ). Then, the clip is closed and MR is evaluated to make sure it has been reduced.

Roberts: How long are the clips from the end of the device? The ones that actually stay on the mitral leaflet.

Grayburn: The clip has 2 sides, posterior and anterior, and each side is about 1 cm long.

Roberts: You insert 1 clip per patient?

Grayburn: A second clip can be inserted if needed. If significant MR remains on either side of the clip, then a second clip can be inserted adjacent to the first clip.

Roberts: You indicated that the clip is placed where the jet is. The jet, however, might be eccentric in the orifice. How do you handle the eccentric jet? You don’t always put these clips in the center of the mitral orifice?

Grayburn: The device was designed initially to mimic the Alfieri stitch, which goes in the center of the mitral orifice. Nevertheless, a small triangular flail segment on the side one can be grasped with the clip. The idea is to put the clip wherever it needs to go. Again, this is carried out under TEE guidance so that one can put the clip right on top of the MR jet and hopefully eliminate it. If there is still a residual jet either medial or lateral to that first clip, a second clip can be inserted.

Roberts: The central portion of the anterior mitral leaflet is devoid of chordae. Thus, a clip placed in the central portion of the anterior leaflet does not interfere with chordae, and it is usually a bit thicker than the posterior leaflet. A flail posterior leaflet which protrudes toward left atrium during ventricular systole is usually thicker than it ought to be. Probably, the thicker it is the easier it is to handle?

Grayburn: Not necessarily. One potential contraindication to placing the clip would be markedly thickened leaflets, those too thick to fit into the clip. Markedly thickened or calcified mitral leaflets would be a contraindication to this procedure.

Roberts: How thick can the combination of both anterior and posterior leaflets be to be inserted into the clip?

Grayburn: We haven’t specifically looked at that or developed specific criteria for that. If we think the leaflets are graspable and will sit down into the clip, well, that’s it.

Roberts: If a hospital or medical institution has physicians, such as yourself, that do these procedures, you attract more patients with pure MR probably than you would otherwise?

Grayburn: Yes, that’s true. We have had a number of patients referred for the clip who ended up having a mitral valve repair because we determined that that procedure was preferable in them to the clip. These patients may not have come to BUMC for an operative mitral repair had we not had the availability of the clip.

Roberts: That same scenario is probably happening with the percutaneous aortic valve implantation without replacement.

Grayburn: I think it is.

Roberts: After you get the clip in place, are you always pleased? Sometimes do you wish that it had been placed a little further to the right or to the left? How often are you pleased with your performance?

Grayburn: There have in fact been times on initial deployment that we have decided that we missed the jet origin either medially or laterally. One beauty of the clip system is that the clip can be released, repositioned, and redeployed. We have done that on several occasions. We have not had a failure at BUMC yet. All of our clips have reduced MR to 2+ or less. We have not had a clip detach or a clip embolize. There have been a handful of clips that have detached from 1 leaflet and subsequently not redeployed. These few patients have gone to surgery. One concern early on was that if a clip was unsuccessful, would surgical repair then be precluded? Argenziano and colleagues demonstrated that mitral valves containing failed clips could still be repairable.

Roberts: Of the mitral clip procedures done at BUMC, there have been no failures? You have not had to send any patient to surgery on an emergency basis or within a few weeks after the percutaneous procedure? You’ve done 24 cases at BUMC?

Grayburn: Correct.

Roberts: How many percutaneous mitral clip procedures do you have to do to “fulfill” the learning curve?

Grayburn: We are just now examining that question. The learning curve varies according to the skill of the operator. By the time we had done 10 cases, we were quite confident that we knew what to do. But the learning curve involves more than 1 thing. First, it involves selecting the right patient. Second, it involves procedural details. We learned early that the site of the transseptal puncture is crucial.

Roberts: The number 1 reason for not putting a percutaneous clip in a patient with pure MR, assuming that there is no dysfunction of the aortic valve or need for simultaneous coronary bypass grafting, is what?

Grayburn: It’s not having enough MR. Nearly 50% of the patients referred to me for evaluation do not have severe MR. Their echocardiogram was misinterpreted. They often did not have the quantitative measures that are recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography. One difficulty with this whole area is that we are not as good as we think we are at grading the severity of MR echocardiographically. Further quantitating the degree of MR once a clip is in place is even more difficult. When turning on a water hose, a steady flow comes out. If you then put your thumb over the nozzle of that water hose, it results in a massive spray. Once the clip is placed, a spraylike jet results, and it looks a lot worse on color Doppler than it looks on angiography. It looks a lot worse than it probably is. We have some difficulty grading the degree of MR after the clip is placed.

Roberts: That’s in the operating room?

Grayburn: Both the operating room and subsequently.

Roberts: Subsequently, by transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiography?

Grayburn: Either one. The first patient that we did 5 years ago was a 46-year-old man on disability. He was unable to work. After we did the clip procedure in him, he got a job as a truck driver, and he still has it today. He’s active and very happy. The core lab graded his MR as moderate (2+) after the clip. I was convinced that his MR was less than that because of how well he’s done and because the left ventricular angiogram after clip placement showed no MR at all. Recently, I did a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study on him, and his regurgitant volume was 6 ml. In other words, his forward stroke volume and his total left ventricular stroke volume were essentially the same, confirming again that he did not have significant MR at all, even though the color Doppler jet looked as if he had significant MR. This is clearly a spray effect, analogous to putting your thumb over a water hose and creating a huge spray.

Roberts: Should you do an MRI on every one of these patients postoperatively?

Grayburn: I don’t know that that’s what we need to do, but I think we need to work hard at finding better ways of grading and quantifying MR after the clip and even before the clip.

Roberts: You are one of the world’s authorities on echocardiography. If you have difficulty reading the degree of MR in these patients after insertion of the clip, the elsewhere general echocardiographer must have a terrible time making a proper evaluation?

Grayburn: There are some quantitative measures of MR that are supposed to be done and have been recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography, but unfortunately, these measurements are not done routinely in many labs. I often see outside echocardiograms in which the color flow is turned on but none of the quantitative measurements have been done or even attempted. I think the quality of echocardiography that is done in a high-volume center that focuses on mitral valve disease and other valve disease is quite a bit different than what is done in the community. I strongly believe that we need to have centers of excellence in valvular heart disease where patients can come and know that they are going to be evaluated by very good clinicians with state-of-the-art echocardiography and MRI, if needed, with state-of-the-art surgeons who are experts in mitral valve repair. This is a team-interactive approach to determine what’s best for the patients.

Roberts: This procedure looks pretty reasonable to me, an outsider. On the other hand, the percutaneous aortic valve procedure for patients with aortic stenosis does not look nearly as reasonable to me. All patients you have done have 3+ or 4+ MR. Do you do this procedure on some asymptomatic patients?

Grayburn: Yes.

Roberts: What are criteria for the asymptomatic ones versus the symptomatic ones?

Grayburn: There is debate here. There are no randomized control trials, but there are some studies from the Mayo Clinic, in particular, that suggest that patients with flail mitral leaflets have a poor prognosis even if they are asymptomatic, and, therefore, they should be operated.

Roberts: When you say “flail,” that’s just 1 portion of either posterior or anterior leaflet that is prolapsing into or toward left atrium during ventricular systole?

Grayburn: With flail, there is loss of coaptation, and usually a torn chord is visible. These patients tend to have a worse prognosis than patients with MR but no flail leaflet. Some investigators believe that if a leaflet is flail in an asymptomatic patient, that should warrant operative repair. The guidelines also recommend that an asymptomatic patient with pure MR should be considered for surgery if there is evidence that the left ventricle is dilating or that the left ventricular ejection fraction has fallen below 60%. Also, the presence of pulmonary hypertension or atrial fibrillation might make operation more advisable in an asymptomatic patient.

Roberts: New-onset atrial fibrillation or long-term?

Grayburn: New-onset in particular.

Roberts: And how much pulmonary hypertension?

Grayburn: A right-sided heart catheterization would be recommended to measure pulmonary vascular resistance and left atrial pressure to determine how much of the pulmonary hypertension is from the MR.

Roberts: In general, a pulmonary arterial systolic pressure >50 mm Hg would concern you?

Grayburn: Yes.

Roberts: How much does a mitral clip device cost? When the FDA approves this device, presuming that’s going to happen, what is the speculation regarding cost?

Grayburn: The current price that we pay for the clip is $18,000. That’s a “clip package.” It is the same cost if we put in 1 or 2 clips.

Roberts: Is the company that presently is producing these devices going to have competition? Are there other companies trying to develop a similar device?

Grayburn: There are a number of companies developing different techniques for repairing the mitral valve percutaneously. The devices vary from annuloplasty-type procedures to procedures that address the leaflets or the chords. Some companies have developed artificial chords that can be put in percutaneously for ruptured chordae. A number of companies have developed devices designed to shrink the mitral annulus. Most were developed as coronary sinus devices. I doubt that these devices are going to succeed, because of anatomical considerations. One computed tomographic study showed in almost 2/3 of patients that the coronary sinus overlapped a portion of the left circumflex coronary artery, so there is a risk of tying off or occluding this major artery with a coronary sinus cinching device. Other studies have shown that the coronary sinus is a centimeter or 2 cephalad to the mitral annulus, a distance too far away to shrink the annulus. Guided Delivery Systems (Santa Clara, California) has a device that goes into the left ventricle and attempts to cinch the mitral annulus from below. Other devices being developed try to pull the papillary muscles together and reposition them, because functional MR is a disease of left ventricular dilation. If the left ventricular cavity can be reduced in size, the amount of MR can be reduced.

Roberts: I understand that the surgeon who started the edge-to-edge operation for pure MR said “that it worked only when you put a mitral ring in also.” You are not putting a mitral ring in the patients in whom you are doing the percutaneous procedure. If you have a patient with chronic pure MR and a large annulus, that patient is not a candidate for the present percutaneous clip?

Grayburn: That is generally correct. In the EVEREST I and EVEREST II trials, patients were excluded if they had a markedly dilated left ventricular cavity. The criterion was a left ventricular cavity diameter in peak systole >5.5 cm. Patients with these massively dilated ventricles and huge mitral annulae would not have been eligible for the MitraClip in those studies. I hear from my colleagues in Europe that they are using the MitraClip procedure in patients with markedly dilated left ventricles from ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Roberts: That’s functional MR?

Grayburn: Yes. I was surprised, but I understand that they are achieving early success in these type patients. Surgery for functional MR utilizing an annuloplasty ring appears early to reduce the degree of MR, but later the MR worsens again. It is important to look at the specific mitral anatomy of each patient and determine what is best in each of them. In functional MR with a dilated left ventricle, sometimes just medical therapy reduces ventricular cavity size and decreases the amount of MR. Cardiac resynchronization therapy also may reduce the degree of MR. Functional MR appears not to be 1 disease but has several mechanisms, including annular dilatation, which may be either symmetrically dilated or asymmetrically dilated. Is there myocardial viability? Should the patient be revascularized? Is there a left bundle branch block? Should the patient get cardiac resynchronization therapy? Is this primarily tenting, and if so, would chordal cutting decrease the MR? Cutting the basal chordae may help relieve tenting and lessen the amount of MR. We must individualize each patient.

Roberts: About 30 years ago, I was involved in a necropsy study in which we measured the circumference of mitral annulus as well as that of other valve annulae. The normal mitral annulus in adults is about 9 cm in circumference. In persons with ischemic cardiomyopathy or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, the annulus is dilated but usually not more than about 2 cm. Thus, from 9 to 11 cm, about a 20% increase. In patients with mitral valve prolapse, in contrast, the mitral annulus circumference may increase to as much as 19 cm. In actuality, the only cases with huge annulae I have seen at autopsy are patients with mitral valve prolapse, particularly when associated with the Marfan syndrome. Have you encountered arrhythmias or conduction disturbances or atrial septal defect as consequences of this procedure? What complications have occurred?

Grayburn: The complications that have occurred would be partial clip detachment, where the clip comes off 1 leaflet. So far, the clip has been detached from only 1 leaflet. If it becomes detached from both leaflets, embolism, of course, could be the consequence. At this point, I am aware of 37 patients who have undergone mitral surgery following percutaneous clip insertion, but not all of those cases were clip detachment; most were failures to completely relieve the MR. In 17 patients, the clip was not even deployed because of failure to reduce MR severity.

Roberts: Or you didn’t get the clip attached?

Grayburn: If one does not get the clip attached, it can be removed. If the clip cannot be attached or if it does not relieve the MR, the clip can be removed completely and surgery performed. Another complication is return of the MR after the clip has been inserted. Surgery then would be necessary. There are obvious vascular complications that might occur with any catheterization procedure, including a groin hematoma or bleeding. The most feared complication is perforation of the heart with the clip hardware causing acute tamponade. Fortunately, that is rare.

Roberts: That was mainly left atrial wall?

Grayburn: Yes, mainly left atrial perforation either by the wire, which is a very stiff wire, or by the clip itself as it’s coming out of the sheath. These patients are prone to atrial fibrillation anyway because of their mitral valve disease, but as far as I can tell, there is no increased frequency of atrial fibrillation or other arrhythmias from use of the clip.

Roberts: And no conduction disturbances?

Grayburn: Correct. The device does not go anywhere near the conduction system.

Roberts: What if the patient has mitral annular calcium? Do you stay away from that? How do you handle those patients?

Grayburn: On TEE, we determine the severity of mitral annular calcium and also subvalvular calcium at the tips of the papillary muscles or on the chordae. Excessive mitral annular calcium may prevent us from successfully deploying a clip.

Roberts: How old are most of your patients?

Grayburn: At BUMC, our patients have ranged from 30 to 91 years (mean 60).

Roberts: Postoperatively or postprocedure, what drugs do you give these patients? How long are they in the hospital?

Grayburn: If the procedure goes well without any complications, they go home the following day. All but 1 of our patients at BUMC has gone home the following day. That 1 patient had a groin hematoma and required transfusions and stayed 3 days in the hospital. Typically the patient arrives in the morning, gets the procedure done, and goes home the following morning.

Roberts: Are they on heparin during the procedure?

Grayburn: Yes. Once the transseptal puncture is done, heparin is started, and the activated clotting time is measured. We try to keep it above 250. Then we put them on aspirin and clopidogrel for 3 months postprocedure.

Roberts: Have there been any emboli, not of the device, but an event interpreted as embolus in any of the patients late postop?

Grayburn: Remember that these patients are also at risk for atrial fibrillation, so if someone were to have an embolic event, one would have to try to differentiate whether this was due to atrial fibrillation and a clot or whether it was related to the clip. It’s pretty clear to me that it’s not the clip. There has not been any description of a thrombus attached to the clip. The clip is very quickly covered by fibrous tissue, and in the cases that have gone to surgery after a clip, there is a very dense tissue fibrous grown over the clip. The clips appear to be nonthrombogenic.

Roberts: Is there worry about too many interventionalists getting involved with this procedure when and if it is approved by the FDA?

Grayburn: I think 1 of the key items that is going to be necessary to get FDA approval is to have a plan in place to limit this procedures to centers of excellence. Evalve does have such a plan in place.

Roberts: Evalve is a company?

Grayburn: Yes. This is going to be something very carefully watched. I think all companies involved in percutaneous valvular disease are quite aware of this problem. These devices must be restricted to hospitals that have high volume, expertise in all of the areas involved, including imaging, clinical cardiology, intervention, and surgery. If all interventionalists started doing this complicated procedure, the complication rate would be higher.

Roberts: How many centers of excellence do we need in the USA for valvular heart disease?

Grayburn: In my opinion, 50 would probably be sufficient. There needs to be some geographic diversity, but 50 centers of excellence with top-flight surgeons, top-flight cardiology teams should be sufficient.

Roberts: Essentially 1 per state?

Grayburn: More populous states will need more. The number may need to be 100.

Roberts: How do you follow these patients after this procedure?

Grayburn: The study protocol requires that they get an echocardiogram 1 day after the procedure.

Roberts: That’s transthoracic?

Grayburn: Yes. Then another one at 1 month, and then we follow them every 6 months after that by echocardiography and clinical examination.

Roberts: What is the latest follow-up so far?

Grayburn: Eight years. There are a handful of patients now that have had the clip for 5 to 8 years.

Roberts: Have any cardiovascular surgeons had a clip put in?

Grayburn: Not that I am aware of, or rather none that will admit to it.

Roberts: Paul, I think this has been very good. Is there anything else you’d like to discuss?

Grayburn: No, I think it’s been a wonderful time, and I appreciate the opportunity to speak with you.

Roberts: Thank you!

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree