and Alessandra Cancellieri2

(1)

Department of Radiology, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy

(2)

Department of Pathology, Maggiore Hospital, Bologna, Italy

Radiology | Giorgia Dalpiaz | |

Pathology | Alessandra Cancellieri |

Fibrosing pattern | Definition | Page 68 |

Fibrosing key signs | Honeycombing Fibrosing reticulation and interface sign Traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis Volume loss | Page 69 Page 70 Page 72 Page 72 |

Ancillary signs | Ground-glass opacity Lobular air trapping Disseminated pulmonary ossification | Page 74 Page 75 Page 76 |

Table | Page 77 |

Fibrosing Pattern

Definition

Fibrosing pattern is defined when retraction and/or remodeling of thoracic structures is visible at the lobular level, often extended to larger portions of the lungs.

Pulmonary fibrosis is histologically defined as the abnormal deposition of dense collagen in lung parenchyma (pink-staining fibrosis). Regardless of the underlying mechanism and duration of injury, fibrosis results into structural damage and pathological remodeling (Please refer to “Non-defining lesions: fibrosis” in the chapter “Thinking trough pathology”).

Fibrotic pattern

The HRCT signs of fibrotic disease are associated with the direct visualization of fibrotic lesions or the effects of retraction and remodeling on pulmonary structures.

Key signs are:

Honeycombing

Fibrosing reticulation and interface sign

Traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis

Volume loss

Ancillary signs are:

Ground-glass opacity

Lobular air trapping

Disseminated pulmonary ossification

The prevalent distribution of the signs, together with the presence of non-parenchymal signs, may be helpful for the diagnosis of a specific disease (please see the table at the end of this chapter).

As well as in fibrosing diseases, in which this pattern is predominant, there are other diseases in which fibrotic signs may be found, albeit less important or sporadic. They are therefore described in the relevant chapter.

Jacob J, Hansell DM (2015) HRCT of fibrosing lung disease. Respirology 20(6):859

Leslie KO (2009) My approach to interstitial lung disease using clinical, radiological and histopathological patterns. J Clin Pathol 62(5):387–401

Dalpiaz G (2017) Fibrosing pattern. In Leslie KO, Wick MR (eds). Practical lung pathology, 3rd edn. Saunders, Philadelphia

Hodnett PA (2013) Fibrosing interstitial lung disease. A practical high-resolution computed tomography-based approach to diagnosis and management and a review of the literature. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 15;188(2):141

Fibrosing Key Signs

Honeycombing

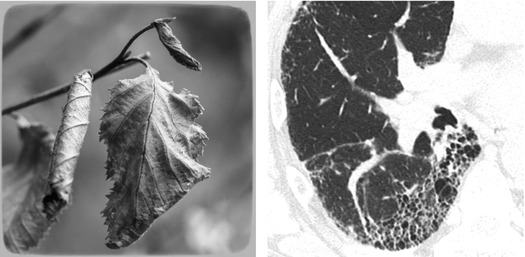

In the latest version from the Fleischner Society on HRCT, honeycomb lung is defined as clustered cystic airspaces, typically of comparable diameters on the order of 3–10 mm but occasionally as large as 2.5 cm. Honeycombing is usually subpleural and is characterized by well-defined walls 1–3 mm in thickness. Although often cited in the literature as being layered ( ), a single layer of subpleural cysts may also be a manifestation of honeycombing. Unfortunately, the HRCT identification of honeycombing is not always straightforward, and there is some disagreement regarding its imaging features, mainly due to conditions that may mimic honeycombing in the axial plane, in particular, severe traction bronchiolectases and emphysema. The coronal or sagittal reconstruction may be useful for the differential diagnosis. Pathology of honeycombing consists of enlarged airspaces lined by bronchiolar epithelium and frequently filled by mucus and inflammatory cells (►, inset). The background architecture has to be altered in order to distinguish honeycombing from peribronchiolar metaplasia, a nonspecific finding in many conditions.

), a single layer of subpleural cysts may also be a manifestation of honeycombing. Unfortunately, the HRCT identification of honeycombing is not always straightforward, and there is some disagreement regarding its imaging features, mainly due to conditions that may mimic honeycombing in the axial plane, in particular, severe traction bronchiolectases and emphysema. The coronal or sagittal reconstruction may be useful for the differential diagnosis. Pathology of honeycombing consists of enlarged airspaces lined by bronchiolar epithelium and frequently filled by mucus and inflammatory cells (►, inset). The background architecture has to be altered in order to distinguish honeycombing from peribronchiolar metaplasia, a nonspecific finding in many conditions.

), a single layer of subpleural cysts may also be a manifestation of honeycombing. Unfortunately, the HRCT identification of honeycombing is not always straightforward, and there is some disagreement regarding its imaging features, mainly due to conditions that may mimic honeycombing in the axial plane, in particular, severe traction bronchiolectases and emphysema. The coronal or sagittal reconstruction may be useful for the differential diagnosis. Pathology of honeycombing consists of enlarged airspaces lined by bronchiolar epithelium and frequently filled by mucus and inflammatory cells (►, inset). The background architecture has to be altered in order to distinguish honeycombing from peribronchiolar metaplasia, a nonspecific finding in many conditions.

), a single layer of subpleural cysts may also be a manifestation of honeycombing. Unfortunately, the HRCT identification of honeycombing is not always straightforward, and there is some disagreement regarding its imaging features, mainly due to conditions that may mimic honeycombing in the axial plane, in particular, severe traction bronchiolectases and emphysema. The coronal or sagittal reconstruction may be useful for the differential diagnosis. Pathology of honeycombing consists of enlarged airspaces lined by bronchiolar epithelium and frequently filled by mucus and inflammatory cells (►, inset). The background architecture has to be altered in order to distinguish honeycombing from peribronchiolar metaplasia, a nonspecific finding in many conditions.

The differential diagnosis between honeycombing and paraseptal emphysema may be difficult; however, honeycombing is usually associated with other features of lung fibrosis, such as volume loss, architectural distortion, fibrosing reticulation, traction bronchiectases, and bronchiolectases. Subpleural cysts without other signs of fibrosis likely represent subpleural emphysema. But one must also keep in mind that emphysema and honeycombing may coexist. The latter entity is defined combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome (CPFE). In these cases, it may be difficult to determine where emphysema ends and honeycombing begins.

Diseases with honeycombing:

IPF: honeycombing is a strong predictor of histologic UIP because it is seen in most cases (about 70 %) and mainly involves subpleural regions and lung bases. However keep in mind that in patients with fibrotic ILD and absence of CT honeycombing, the probability of IPF exceeds 80 % in subjects over age 60 years with one-third of total lung having fibrosing reticulation

Asbestosis: honeycombing is a common finding in advanced-stage disease, predominantly at the basal periphery and posterior region, similarly to what is observed in patients with IPF. Bilateral pleural plaques are crucial for the diagnosis

HP, chronic: honeycombing is common in advanced disease (about 60 %) with possible (non-basal) upper-lobe distribution. Bilateral lobular air trapping is a key for the diagnosis

CVD and drug toxicity: based on the pathologic classification, the frequently observed NSIP pattern related to CVDs (mostly, in patients with scleroderma and rheumatoid arthritis) may be associated with mild honeycombing. In patient with pathologic UIP pattern, honeycombing is frequent. Pleural and pericardial thickening or effusion may coexist and useful for the diagnosis of CVD and drug toxicity. In scleroderma pulmonary arterial hypertension and esophageal dilation (up to 80 % of cases) may be visible

NSIP: honeycombing is uncommon and of minimal extent

Sarcoidosis, fibrotic: occasionally, honeycomb-like cysts are seen in the upper lobes, associated with peribronchovascular fibrosis. Bilateral, symmetric mediastinal and hilar and right paratracheal lymph node enlargement, often calcified, are crucial for the diagnosis. May be present perilymphatic nodules that may be difficult to distinguish from interface sign

Honeycombing in patient with biopsy-proven NSIP may reflect foci of UIP in spite of the histologic diagnosis, since heterogeneity is known to exist among biopsy samples (so-called discordant UIP).

Honeycombing in PPFE is often due to coexistent UIP. Marked irregular pleural thickening and “tags” in the upper zones that merges with fibrotic changes in the subjacent lung are the key signs for the diagnosis.

Hansell D (2008) Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 246(3):697

Arakawa H (2011) Honeycomb lung: history and current concepts. AJR Am J Roentgenol 196(4):773

Watadani T (2013) Interobserver variability in the CT assessment of honeycombing in the lungs. Radiology 266(3):936

Fibrosing Reticulation and Interface Sign

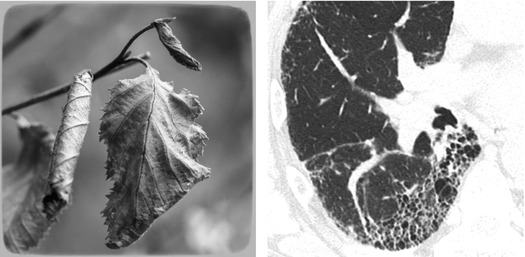

Fibrosing reticular abnormality appears as wavering fine intralobular lines as if they were traced on the lung background by an unsteady hand. The distortion due to fibrosis tends to reduce the recognition of the lobular architecture ( ). Although interlobular septal thickening can be seen on thin-section CT scans with possible association with honeycombing, it is not usually a predominant feature. In the presence of fibrosis, distortion of lung architecture makes the recognition of lobules and thickened septa difficult.

). Although interlobular septal thickening can be seen on thin-section CT scans with possible association with honeycombing, it is not usually a predominant feature. In the presence of fibrosis, distortion of lung architecture makes the recognition of lobules and thickened septa difficult.

). Although interlobular septal thickening can be seen on thin-section CT scans with possible association with honeycombing, it is not usually a predominant feature. In the presence of fibrosis, distortion of lung architecture makes the recognition of lobules and thickened septa difficult.

). Although interlobular septal thickening can be seen on thin-section CT scans with possible association with honeycombing, it is not usually a predominant feature. In the presence of fibrosis, distortion of lung architecture makes the recognition of lobules and thickened septa difficult.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree