Invasive coronary angiography (ICA) is the gold standard in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease (CAD), however, associated with rare but severe complications. Patients with a high pretest risk should be referred directly for ICA, whereas a noninvasive strategy is recommended in the remaining patients. In the setting of a university hospital, we investigated the pattern of diagnostic tests used in daily clinical practice. During a 1-year period, consecutive patients with new symptoms suggestive of CAD and referred for exercise stress test, coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), or ICA qualified for inclusion. The patients were followed for 1 year, and additional downstream diagnostic tests and need of coronary revascularization were registered. A total of 1,069 patients were included. A noninvasive test was the first examination in 797 patients (75%; exercise stress test in 37, CCTA in 450, and SPECT in 310), whereas 272 (25%) were referred directly to ICA. The ICA group had a significant higher pretest probability for CAD, and the percentage of patients with evidence of significant CAD was 31% (84 of 272 patients), whereas 18% (144 of 797 patients) in the noninvasive group (p <0.0001). In the comparison between CCTA and SPECT, there were no significant differences in downstream testing (16% [72 of 444 patients] vs 17% [53 of 310], p = 0.55), and revascularization rate (20% [14 of 69 patients with positive findings] vs 9% [6 of 67], p = 0.09). In conclusion, a noninvasive diagnostic test was chosen as the first test in 3 of 4 patients. Of the patients referred directly for noninvasive examination, 1/5 had significant CAD, whereas 1/3 of those for invasive examination.

The annual incidence of stable angina pectoris is 370,000 in men and 195,000 in women in America. For this large number of patients, an effective diagnosing with a minimal risk is mandatory. Invasive coronary angiography (ICA) is the gold standard but associated with potential complications including transfusion-requiring bleeding (0.5% to 2%) and a combined rate of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke of 0.1% to 0.2%. Therefore, diagnostic methods that can obviate the need for ICA in patients unlikely to require coronary revascularization are desirable. According to the most recent guidelines on management of angina pectoris from the European Society of Cardiology, American College of Cardiology, and American Heart Association, pretest risk stratification is essential. Although patients with a high pretest risk should be referred directly for ICA, the remaining patients should be noninvasively examined. The development of coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) has the potential to reduce unnecessary invasive testing. Several meta-analysis and multicenter studies have compared CCTA to ICA, and these consistently demonstrate a high negative predictive value (99% to 100%) and high sensitivity (99%). The high negative predictive value and sensitivity observed indicate that CCTA may be a qualified gatekeeper to rule out coronary artery disease (CAD). However, the specificity and positive predictive value of CCTA are rather low, 83% and 64%, respectively. In the present study, we set out to investigate the pattern of diagnostic tests used in daily clinical practice in the era of CCTA with particular focus on (1) the need for further diagnostic examinations, (2) the rate of subsequent ICA with nonobstructive CAD, and (3) the proportion of later coronary revascularization procedures.

Methods

This retrospective study comprises consecutive elective patients with new symptoms suggestive of CAD, who during 2012 were admitted to a 1,000-bed university hospital serving as a tertiary referral center for a region with 1.2 million inhabitants and as a local hospital for a catchment area of 300,000 residents. Based on clinical judgment, the physicians chose the first diagnostic test and made all subsequent clinical decisions. All patients referred for exercise stress test (ExST), CCTA, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), or ICA were qualified for inclusion. Patients were only included once and grouped according to the first examination (ExST, CCTA, SPECT, and ICA, respectively). Data were collected from patients’ medical records. Patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome, a history of CAD (myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, or coronary artery stenosis ≥50% on a previous ICA), and congenital, valvular, or cardiomyopathic heart disease were excluded.

Diabetes mellitus was defined as the use of antidiabetic medication or if documented in the patient files. Only medications at the time of cardiac examination were registered. Symptoms that led to referral were divided into typical angina pectoris, atypical angina pectoris, or nonanginal chest pain. Dyspnea and syncope were classified as nonanginal chest pain. Pretest probability was calculated from the modified Diamond model, including age, gender, and type of chest pain.

The results of the 4 examinations, ExST, CCTA, SPECT and ICA, were graded as “positive” or “negative.” ExST was categorized positive if the patient experienced chest pain/discomfort, had significant electrocardiographic changes defined as horizontal or downsloping ST-segment depression ≥0.1 mV, in ≥1 electrocardiographic leads during the test, or if the test was inconclusive. CCTA was categorized positive if at least 1 coronary artery lumen diameter stenosis ≥50% was detected or if a potential significant stenosis could not be excluded (i.e., in case of coronary calcium score >400 Agatston units). SPECT was categorized as positive if the patient had irreversible or reversible ischemia or if a potential perfusion defect could not be excluded. ExST, CCTA, and SPECT were denoted negative if no positive criteria were present. ICA was categorized as positive if at least 1 stenosis (≥50% lumen diameter) was detected in at least 1 coronary artery. Negative ICA was defined as the absence of lumen diameter stenosis ≥50%. The patients were followed for 1 year, and further downstream diagnostic testing, results of a subsequent ICA, and the need for coronary revascularization procedures were registered.

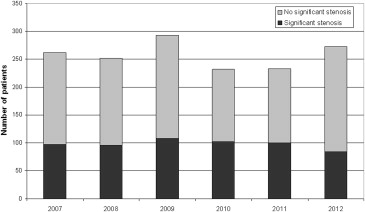

For comparison, data from patients with suspected CAD and referred directly to ICA in 2007 (before the availability of CCTA) and the following 5 years (2008 to 2012) were drawn from The Western Denmark Heart Registry. Patients with a history of known CAD were excluded.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and categorical variables as numbers and frequencies. Means were compared using a 2-sample t test, whereas binary variables were compared using a Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Evaluating the number of ICA from 2007 to 2012, a test for trend for ordered groups was applied. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were performed using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

Results

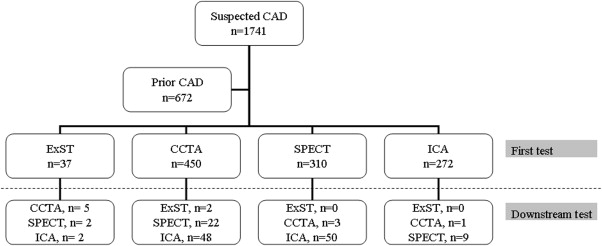

During 2012, a total of 1,069 patients with suspected CAD fulfilled the study inclusion criteria. A noninvasive test was the first cardiac examination in 797 patients (75%) (ExST in 37, CCTA in 450, and SPECT in 310), whereas 272 (25%) were referred directly to ICA ( Figure 1 ). Baseline characteristics of the 4 groups are illustrated in Table 1 . Patients in the ICA group had a significantly higher mean age (p <0.0001). Former and current smoking (65% vs 57%, p = 0.03) and diabetes (20% vs 10%, p <0.0001) were significantly common in the ICA group. Also, patients referred directly for ICA received more medication; thus, the use of antihypertensive drugs (66% vs 49%, p <0.0001) and treatment with statins (47% vs 29%, p <0.0001) were more common compared with the noninvasive group. The ICA group had a higher pretest probability than the patients in the noninvasive group (48% vs 26%, p <0.0001). Furthermore, the SPECT group had a higher pretest probability than CCTA group (29% vs 24%, p = 0.0001). In the CCTA group, the radiation dose was 9.0 ± 1.2 mSv, whereas it was 11.0 ± 3.8 mSv in the SPECT group.

| Variables | All patients (n=1069) | ExST (n=37) | CCTA (n=450) | SPECT (n=310) | ICA (n=272) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years), mean (±SD) | 59.5 (±12.6) | 50.7 (±12.2) | 55.3 (±12.0) | 61.9 (±11.7) | 64.8 (±11.7) |

| Men | 511 (48%) | 25 (68%) | 190 (42%) | 145 (47%) | 151 (56%) |

| Non smoker | 401/979 (41%) | 13/25 (52%) | 195/445 (44%) | 101/249 (41%) | 92/260 (35%) |

| Former smoker | 350/979 (36%) | 7/25 (28%) | 144/445 (32%) | 91/249 (37%) | 108/260 (42%) |

| Current moker | 228/979 (23%) | 5/25 (20%) | 106/445 (24%) | 57/249 (23%) | 60/260 (23%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 123/1003 (12%) | 2/29 (7%) | 24/420 (6%) | 44/286 (15%) | 53/268 (20%) |

| Family history of premature cardiovascular disease | 3/4 (75%) | 207/431 (48%) | 99/199 (50%) | 124/249 (50%) | |

| Medical treatment | |||||

| Platelet inhibitors | 297/887 (34%) | 5/26 (19%) | 94/344 (27%) | 72/255 (28%) | 126/262 (48%) |

| Anticoagulants | 60/876 (7%) | 3/26 (12%) | 14/335 (4%) | 29/255 (11%) | 14/260 (5%) |

| Statins | 305/900 (34%) | 10/26 (39%) | 90/344 (26%) | 83/268 (31%) | 122/262 (47%) |

| Antihypertensive treatment | 475/878 (54%) | 11/26 (42%) | 149/336 (44%) | 142/255 (56%) | 173/261 (66%) |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Typical angina pectoris | 159/1060 (15%) | 4/37 (11%) | 32/444 (7%) | 17/310 (6%) | 106/269 (39%) |

| Atypical angina pectoris | 215/1060 (20%) | 8/37 (22%) | 72/444 (16%) | 57/310 (18%) | 78/269 (29%) |

| Non Cardiac Chest Pain | 686/1060 (65%) | 25/37 (68%) | 340/444 (77%) | 236/310 (76%) | 85/269 (32%) |

| Pretest risk stratification (%), mean (±SD) | 32 (±21) | 28 (±17) | 24 (±17) | 29 (±18) | 48 (±24) |

The percentage of positive test results was 31% (84 of 272 patients) in the ICA, whereas 18% (144 of 797 patients) in the entire noninvasive group (p <0.0001; Table 2 ). No difference between the relative number of additional diagnostic tests in the CCTA and SPECT groups was observed (72 tests in 450 patients vs 53 tests in 310 patients, p = 0.55; Figure 1 ). Among all patients evaluated noninvasively, 3% (21 of 797 patients) had subsequent revascularization, whereas 26% (70 of 272 patients) referred for ICA as the initial test (p <0.0001). Sixty-nine patients had a positive CCTA test result, and this triggered 44 ICA examinations, of which significant CAD was found in 19 and 14 subsequently underwent revascularization. Sixty-seven patients had a positive SPECT result, and this led to 49 ICA examinations, of which 12 had significant CAD and 6 had coronary revascularization procedures performed. In the CCTA group, 20% (14 of 69 patients) with positive findings underwent revascularization, as opposed to 9% (6 of 67 patients) in the SPECT group (p = 0.09). Of patients with positive test results in the ICA group, 83% (70 of 84 patients) underwent revascularization procedures.

| Total | ExST | CCTA | SPECT | ICA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positiv test | 228/1069 (21%) | 8/37 (22%) | 69/450 (15%) | 67/310 (22%) | 84/272 (31%) |

| 1 extra exam | 137/1056 (13%) | 8/36 (22%) | 66/444 (15%) | 53/306 (17%) | 10/270 (4%) |

| 2 extra exams | 4/1056 (<1%) | 1/36 (3%) | 3/444 (<1%) | 0/306 (0%) | 0/270 (0%) |

| 3 extra exams | 0/1056 (0%) | 0/36 (0%) | 0/444 (0%) | 0/306 (0%) | 0/270 (0%) |

| Significant stenosis by ICA | 1/2 (50%) | 19/44 (43%) | 12/49 (25%) | ||

| Outcome of “Positive” results | |||||

| Revascularisation (PCI+CABG) | 91/228 (40%) | 1/8 (13%) | 14/69 (20%) | 6/67 (9%) | 70/84 (83%) |

| Medical treatment | 41/228 (18%) | 1/8 (13%) | 11/69 (16%) | 16/67 (24%) | 13/84 (16%) |

| No treatment required | 86/228 (38%) | 4/8 (50%) | 43/69 (62%) | 39/67 (58%) | 0/84 (0%) |

| Lost of follow-up | 10/228 (4%) | 2/8 (25%) | 1/69 (1%) | 6/67 (9%) | 1/84 (1%) |

Based on data from the Western Denmark Heart Registry, the number of patients referred directly for ICA did not differ over the past years (p = 0.85). Neither the absolute nor the relative number of patients with significant CAD on ICA differed significantly over the same period of time: 97 (37%), 96 (38%), 108 (37%), 102 (44%), 100 (43%), and 84 (31%) (p = 0.75; Figure 2 ).

Results

During 2012, a total of 1,069 patients with suspected CAD fulfilled the study inclusion criteria. A noninvasive test was the first cardiac examination in 797 patients (75%) (ExST in 37, CCTA in 450, and SPECT in 310), whereas 272 (25%) were referred directly to ICA ( Figure 1 ). Baseline characteristics of the 4 groups are illustrated in Table 1 . Patients in the ICA group had a significantly higher mean age (p <0.0001). Former and current smoking (65% vs 57%, p = 0.03) and diabetes (20% vs 10%, p <0.0001) were significantly common in the ICA group. Also, patients referred directly for ICA received more medication; thus, the use of antihypertensive drugs (66% vs 49%, p <0.0001) and treatment with statins (47% vs 29%, p <0.0001) were more common compared with the noninvasive group. The ICA group had a higher pretest probability than the patients in the noninvasive group (48% vs 26%, p <0.0001). Furthermore, the SPECT group had a higher pretest probability than CCTA group (29% vs 24%, p = 0.0001). In the CCTA group, the radiation dose was 9.0 ± 1.2 mSv, whereas it was 11.0 ± 3.8 mSv in the SPECT group.