LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learning Objectives

The student will be able to define emphysema and chronic bronchitis and differentiate their various forms, including etiology, pathogenesis, gross and microscopic morphology, and clinical presentation.

The student will be able to describe the histological presentation of asthma, particularly as it may involve both airways and lung parenchyma.

The student will be able to describe the development and appearance of bronchiectasis as it evolves from an initial obstructive process.

Obstructive lung diseases are characterized by reductions in airflow due to increased resistance from partial or complete airway obstructions at any level. Such obstructions can arise from direct narrowing of the airway lumen or by decreased elastic recoil of the pulmonary parenchyma surrounding the airways, which has the effect of reducing lumen caliber. The many causes of obstructive disease include tumors, aspirated foreign bodies, asthma, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, cystic fibrosis, and bronchiolitis. This chapter will focus on the pathology of emphysema, chronic bronchitis, asthma, and bronchiectasis. Bronchiectasis is included here although it occurs as a result of airway obstruction, rather than being a cause in itself. The chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPDs) comprise emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Though it is possible to have emphysema without chronic bronchitis or the converse, most patients have some degree of both, though one may dominate the clinical scenario. They share common etiologies, the most significant of which is tobacco smoking. Despite this significant association, most smokers do not develop COPD.

PATHOLOGY OF EMPHYSEMA

Emphysema is defined morphologically as the irreversible enlargement of airspaces distal to the terminal bronchioles, due to destruction of airspace walls and without obvious fibrosis. Emphysema is present in approximately one-half of adults at autopsy, most of whom were asymptomatic. Emphysema is further subdivided into four subtypes based on the anatomic distribution of the airspace enlargement: centriacinar (centrilobular), panacinar (panlobular), distal acinar (paraseptal), and irregular.

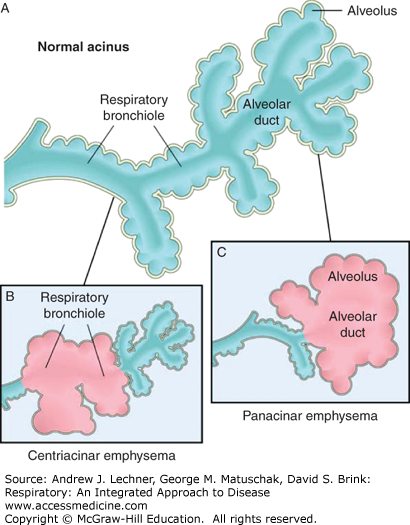

Centriacinar emphysema (Figs. 20.1 and 20.2) is characterized by airspace enlargement at the level of the respiratory bronchioles, sparing the distal alveoli. Anatomically, the several acini that comprise a lobule (Chap. 2) are arranged such that their respiratory bronchioles are grouped in the center of the lobule. This anatomic arrangement underlies the alternate name, centrilobular emphysema. Centriacinar emphysema accounts for more than 95% of those cases of emphysema with clinically significant airway obstruction. It is more pronounced in the upper lobes and is the type of emphysema most strongly associated with smoking.

FIGURE 20.1

The two major patterns of emphysema. A. Normal acinar structure. B. Centriacinar emphysema that involves respiratory bronchioles but spares more distal alveoli. C. Panacinar emphysema that involves the alveolar ducts and more distal alveoli. From Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th ed.; 2010.

Panacinar emphysema (Figs. 20.1, 20.2, 20.3) is characterized by airspace enlargement at the level of the alveolar ducts and more distally. At the gross level, airspace enlargement appears to affect the entire lobule, giving rise to the alternate name, panlobular emphysema. Panacinar emphysema accounts for less than 5% of cases of emphysema with clinically significant airway obstruction and is more pronounced in the lower lung zones. It is the type of emphysema most strongly associated with α1-antiprotease (α1-PI) deficiency (Chap. 22).

Distal acinar emphysema (Fig. 20.4) involves distal airspaces and is most prominent adjacent to the visceral pleura and to the connective tissue septa that define the lobules. Distal acinar emphysema typically does not result in clinically significant airway obstruction. It is more severe in the upper half of the lungs and likely represents the underlying lesion resulting in spontaneous pneumothorax in young adults.

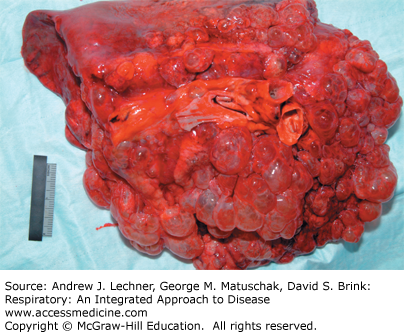

Emphysema that does not show centriacinar, panacinar, or distal acinar distribution is called irregular emphysema. Irregular emphysema is very common adjacent to foci of scarring and does not typically cause significant airway obstruction. In any form of emphysema, large, distended sacs of air or bullae can form. Any subtype of emphysema with bullae is likely to be referred to as bullous emphysema (Fig. 20.5). In its most severe forms, emphysema is difficult to subclassify (Fig. 20.6).

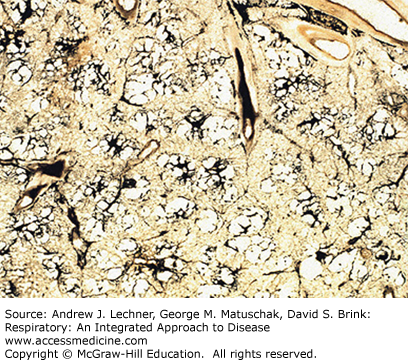

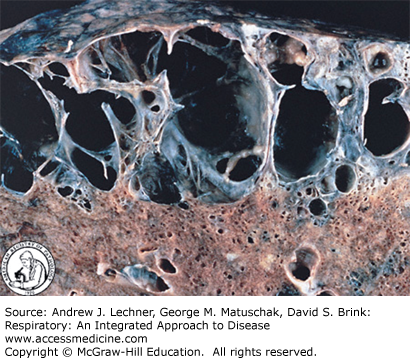

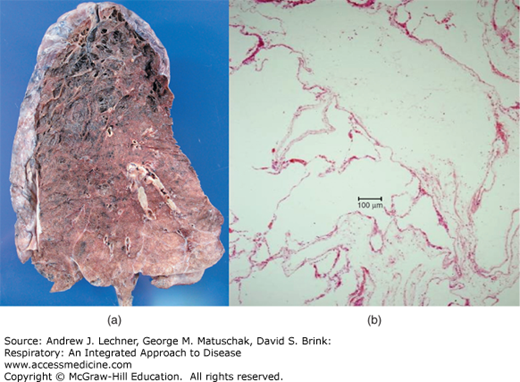

FIGURE 20.6

(a): Severe emphysema. Particularly evident in the upper portion of the cut surface of the lung, the pulmonary parenchyma droops below the plane of section, imparting a web like appearance. From Kemp WL, Pathology: The Big Picture, McGraw-Hill, 2008. (b): Low power photomicrograph of severe emphysema. The main finding is the absence of tissue. Note how large airspaces are and how few alveolar septa are present. When severe as here, one cannot determine whether the morphology reflects the centriacinar, panacinar, distal acinar, or irregular form.

The pathogenesis of emphysema is generally considered to involve excess protease and/or elastase activity that is insufficiently opposed by antiprotease regulation (Fig. 20.7). The probable sequence begins with neutrophil sequestration in capillaries, migration into airways and alveoli, and their stimulation to release elastase-containing granules that degrade elastic tissue in the absence of sufficient antiprotease activity (Chap. 10). Such antiprotease insufficiency can be due to α1-PI deficiency and/or the functional impairment of it and other antiproteases (Chap. 22).