Pararenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm—Open Repair

BO WANG, ARASH BORNAK, ATIF BAQAI, JORGE REY, and OMAIDA C. VELAZQUEZ

Presentation

A 62-year-old woman is seen in the emergency room (ER) for acute onset of lower abdominal pain radiating to the left flank. A quick chart review reveals that the patient has an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) discovered incidentally 3 years prior to this visit and diagnosed during a sigmoid diverticulitis workup. At that time, the aneurysm measured 4.6 cm (AP) in maximum diameter, limited to the infrarenal aorta with a 1.8-cm neck. The patient was discharged after a course of antibiotics and never followed up with vascular surgery. In the ER, an aortic ultrasound reveals an AAA approximately 6.9 cm in diameter. Vascular surgery is consulted for a symptomatic AAA. The patient’s past medical history also includes a myocardial infarction that occurred 4 years ago. She had drug-eluting stents placed on that occasion. Her past surgical history includes perforated diverticulitis, followed by a Hartmann’s procedure and a colostomy reversal. She has a 50-pack-year history of smoking and is currently a smoker. Her current medications include aspirin, simvastatin, and Lopressor. On physical examination, the patient is hypertensive (178/96 mm Hg) with a tender pulsating epigastric mass. The patient’s femoral and pedal pulses are palpable. The rest of her physical examination is unremarkable. Her medical records also note the result of a recent Persantine stress thallium test indicating a myocardial scar involving the inferolateral region of the left ventricle, but no evidence of reversible myocardial ischemia.

Differential Diagnosis

AAAs are often diagnosed incidentally on computed tomography (CT) scan performed for other abdominal pathologies. Occasionally, an abdominal x-ray may reveal the calcified rim of the aneurysmal aorta prompting further workup. Most AAAs remain asymptomatic until they present with acute symptoms indicating impending, contained, or free rupture. Free rupture is commonly associated with sudden severe abdominal or back pain, syncope, and death.

Aortic aneurysms may become symptomatic with abdominal, back, groin, or flank pain. Such nonspecific signs and symptoms may be related to other abdominal pathologies ranging from a simple urinary tract infection to pancreatitis, diverticulitis, or other inflammatory processes involving the abdominal viscera. Therefore, the workup should not only include an accurate anatomical evaluation of the abdominal organs by radiologic means but also a complete laboratory exam including a full metabolic panel, pancreatic enzymes, and urinary sample. Two other problematic key differential diagnoses should be considered during workup: aortic dissection and acute myocardial infarction.

Diagnosis and Treatment

A computed tomography angiography (CTA) is the most frequent and accurate radiologic imaging that can be obtained for suspected symptomatic aneurysm. Two characteristic findings are worth mentioning in the case of symptomatic aneurysms, which make the diagnosis highly probable. First, on physical exam, the aortic aneurysm is exquisitely tender on palpation. The sensitivity depends, however, on the size of the aneurysm and patient’s body habitus. Second, in hypertensive patients, lowering the systemic blood pressure may alleviate the pain. If a symptomatic aneurysm is suspected, an arterial line should be placed, permissive hypotension should be allowed, and/or the patient’s blood pressure should be pharmacologically decreased and controlled during workup completion.

Workup

CT Angiogram of the Abdomen

The laboratory results are all normal including blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 14 mg/dL and creatinine level of 0.56 mg/day and no anemia.

The above case presents a stable patient with evidence of an expanding symptomatic AAA on ultrasound that will most likely require surgical repair. A high-resolution (1.5- to 3-mm thin sections) CTA including the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis should be performed to provide an accurate anatomic detail of the aneurysm. It will reveal any involvement of the visceral aorta and iliac arteries, guiding the treatment options for either an endovascular or open repair. To further guide the surgical treatment, the surgeon can also appreciate severe angulations and identify the location and distances between renal and visceral vessels, as well as the presence of coexistent occlusive disease in the iliac, renal, and splanchnic vessels (Figs. 1 and 2). The 3D-reconstructed images (Fig. 2) are very helpful in treatment planning, allowing a spatial understanding of the aneurysm and aorta.

FIGURE 1 CTA coronal view of the aneurysm and aortic branches. Black arrows: origin of the renal arteries. Arrowhead: mural thrombus. Mural thrombus is visible between the contrast in the lumen and aortic wall calcification.

FIGURE 2 A and B: 3D reconstruction images help delineate the aneurysm sac, renal arteries’ location, and visceral arteries.

The sudden onset of abdominal pain may also represent a contained rupture, aortic dissection, aneurysm/aortic inflammation, or even infection. All these entities would be evaluated on CTA.

As an alternative to CTA imaging, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can be performed in order to avoid exposure to iodinated products. This modality is lengthy, can overestimate stenotic lesions, and does not reliably depict calcifications. Moreover, for patients with baseline chronic renal insufficiency, the predisposition for gadolinium-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis has made this modality less attractive than in the past.

CTA Report

There is a fusiform pararenal AAA measuring up to 6.4 cm in maximum diameter, with extensive mural thrombus (Fig. 1) and with no rupture, dissection, or inflammation. The right renal artery is noted to be lower than the left renal artery. The aorta is tortuous deviating to the left of midline. The aneurysm extends from the lower end to the left renal artery to the iliac bifurcation. Extensive mural atherosclerosis extends into the bilateral iliac arteries and branches. The origins of the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) are patent, while the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) is thrombosed. Focal stenosis of the proximal common iliac arteries is noted with some poststenotic dilatation. This is a pararenal AAA, specifically a juxtarenal (not suprarenal) AAA.

Case Continued

The patient’s blood pressure is decreased and controlled with a labetalol intravenous drip, and her pain is thus resolved. You inform the patient of the findings and her surgical options. The patient inquires whether she is a candidate for “stent graft” repair of her AAA. The patient’s workup has shown a 6.4-cm juxtarenal AAA. The renal arteries and visceral branches are not involved.

Because the aneurysm extends to the level of the left renal artery, the patient is not a good candidate for an endovascular AAA repair using currently available endografts approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). An open repair should be planned. Customized fenestrated and branched devices are currently under investigation in the United States and used electively in surgically high-risk patients in a few centers. Outside companies’ Instructions for Use (IFU) and other endovascular options are available. In urgent and emergent situations, surgeon-modified fenestrated endografts have been used in extremely high-risk patients. Other endovascular alternatives including “chimney” or “snorkel” endografting have been used in order to preserve visceral perfusion.

The patient presents with signs of impending rupture, which represents a surgical urgency. The patient should be admitted and medical management optimized. Given her past cardiac history, a baseline echocardiogram should be obtained to guide intra-anesthetic management that carefully balances hydration versus pressors. This is not an elective case; thus, an extensive preoperative workup is not required in this setting.

Test Report

Echocardiogram

Hypokinetic area visualized in the left ventricle with an ejection fraction of 40%. This is essentially unchanged since her last cardiac workup.

Surgical Approach

This is a high-risk surgery in a surgically high-risk patient given her cardiac comorbidities. A left retroperitoneal (RP) approach is chosen. RP exposure is in particular indicated in patients with multiple previous intraperitoneal procedures or infections because of the adhesions generated by these processes, as well as in patients with abdominal wall stomas, ectopic kidneys, or inflammatory aneurysms. The left RP approach, with or without mobilization of the left kidney anteriorly, facilitates exposure of the suprarenal aorta and visceral arteries; it is also associated with lower perioperative pulmonary complications.

Because of the extent of the aneurysm, a clamp above the renal arteries will be necessary. This will allow the surgeon to perform a proximal graft anastomosis to the short aortic stump below the renal arteries. Occasionally, intraoperative palpation of the aorta may reveal extensive calcification of the aorta just above the renal arteries and a supraceliac clamp may be necessary.

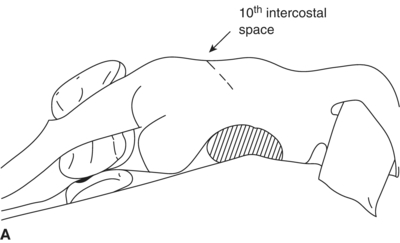

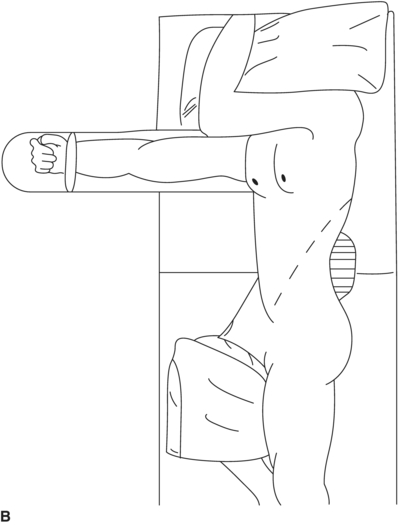

Operative Details

The patient is placed in a right lateral decubitus position with the left side of the torso rotated approximately 45 degrees. The patient is positioned on a beanbag to maintain this posture, and the table is flexed optimally with the kidney rest elevated (Fig. 3). A left RP incision starts at the lateral border of the left rectus muscle midway between the pubis and umbilicus. It extends superiorly (5 cm medial to the anterior-superior iliac spine), curving upward and laterally at the costal margin to follow the course of the 10th interspace. Incisions centered lower, onto the 11th or 12th rib, offer less exposure to the suprarenal aorta. The left ureter should be identified immediately and protected. Ligation of the junction of the gonadal vein with the left renal vein provides the exposure needed to appropriately isolate the infrarenal neck (Fig. 4). Superior mobilization of the left renal vein facilitates exposure of the aortic neck up to the level of the left renal artery. An alternative approach is to mobilize the left kidney anteriorly and medially, a maneuver that is required for adequate exposure of suprarenal aortic pathology. A large lumbar vein that drains into the posterior wall of the left renal vein should be ligated early to avoid avulsion. Visible lumbar arteries are clipped behind the aneurysm. The left crus of the diaphragm is divided for exposure up to 4 to 6 cm above the celiac axis. The next step is to expose the distal anastomotic site at the level of the bifurcation of the aorta. Common iliac arteries are exposed. Before cross-clamping, systemic heparinization is initiated. The iliac arteries are clamped, first distally and then the aorta is clamped proximally in order to prevent embolization. The aneurysm is opened, the thrombus is evacuated, and any bleeding lumbar arteries are suture ligated from within the aneurysmal sac. An end-to-end anastomosis between the prosthetic graft and the aorta is performed proximally first, then the clamp is released, and the graft is clamped below the renal arteries. Hemostasis is obtained, and distal anastomosis is then performed. The distal anastomosis may be to the aortic bifurcation (tube graft) or to the iliac arteries (bifurcated graft). Before releasing the clamps, back bleeding and forward bleeding are allowed, the graft is flushed profusely with heparin saline solution and anastomosis completed. Communication with the anesthesiologist before releasing the clamps is important to adjust blood pressure and avoid sudden hypotension. In patients with stenotic/occlusive disease of the celiac axis, SMA, and/or internal iliac arteries, reimplantation of the IMA should be considered in order to avoid bowel and pelvic ischemia (Table1).

FIGURE 3 A and B: The patient positioned for a left retroperitoneal (RP) approach.