15 Pacing in Neurally Mediated Syncope Syndromes

Syncope is the transient loss of consciousness with subsequent complete resolution and without focal neurologic deficits, resulting from cerebral hypoperfusion, and not requiring specific resuscitative measures. The neurally mediated syncope syndromes are a collection of clinical disorders of heart rate and blood pressure regulation, caused by autonomic reflexes.1,2 These often include bradycardia, which has led to attempts to use cardiac pacing as a therapy for carotid sinus syncope and vasovagal syncope, the most common of the neurally mediated syncopes.

There are now several expert consensus conferences and position papers on these syndromes.3,4 This chapter reviews recent progress in determining the usefulness of pacemakers in the neurally mediated syncope syndromes.*

Carotid Sinus Syncope

Carotid Sinus Syncope

Clinical Perspective

Carotid sinus syncope (CSS) is a syndrome of syncope associated with a consistent clinical history, carotid sinus hypersensitivity, and the absence of other potential causes of syncope. Historical features that suggest the diagnosis are syncope or presyncope occurring with carotid sinus stimulation that reproduces clinical symptoms, or fortuitous Holter monitoring or other documentation of asystole during syncope following maneuvers that could presumably stimulate the carotid sinus.5–9 The incidence of carotid sinus syncope is low, about 35 per 1 million population per year.10 CSS occurs in older patients, mainly in men. It tends to occur abruptly, with minimal prodrome, and only half of patients may recognize a precipitating event. These events typically include wearing tight collars, shaving, head turning (as in looking to the back in a car), coughing, heavy lifting, and looking up.

Symptoms of CSS range from mild presyncope to profound loss of consciousness, occasionally with significant injuries. Some patients may not recall losing consciousness, instead presenting with unexplained falls. In Great Britain, fits, faints, and falls are often investigated in an integrated setting with a comprehensive clinical pathway. Elderly patients with unexplained falls may have positive carotid sinus massage (CSM) responses, suggesting that carotid sinus syncope is responsible for many unexplained or recurrent falls.11,12 However, physiologic carotid sinus hypersensitivity is much more common than carotid sinus syncope, and care should be taken in the interpretation of these results.

Natural History

Little is known about the natural history of CSS. Even though it may have a substantial effect on quality of life, CSS has not been shown to affect mortality significantly, and patients who receive therapy do not appear to have worse prognoses than the general population. Even in the absence of pacing, only 25% of patients may have a syncope recurrence.13,14

Rationale for Pacing

Table 15-1 lists recommendations and other considerations in pacing for CSS.

TABLE 15-1 Summary of Pacing for Carotid Sinus Syncope (CSS)

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Goal | Prevent reflex bradycardia and compensate for reflex hypotension |

| Prevent syncope | |

| Level of evidence for success | Observational studies and open-label, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) |

| No double-blind studies | |

| Consensus recommendations | Class I: Recurrent syncope, with syncope induced by carotid sinus massage |

| Class IIa: Recurrent syncope, with profound bradycardia induced by carotid sinus massage | |

| Patient selection | Syncope and positive carotid sinus massage |

| Programming considerations | Atrioventricular sequential pacing |

Physiology

The carotid sinus reflex is an integral component of the homeostatic mechanisms of blood pressure regulation.15 Increases in intrasinus pressure stimulate mechanoreceptors, which participate in an afferent arc terminating in the brainstem. The efferent arc travels to peripheral end organs through vagal efferents, which augment cardiac vagal input and slow heart rate, and through the spinal cord to inhibit peripheral sympathetic activity in skeletal vasculature, resulting in peripheral vasodilatation. This reflex maintains blood pressure within a narrow range.

An abnormal carotid sinus reflex can cause exaggerated responses of heart rate and blood pressure. Some evidence suggests that the major defect in carotid sinus hypersensitivity does not reside in the carotid sinus or in its neural efferents,16,17 or in the brainstem. Rather, the neuromuscular structures surrounding the carotid sinus may be involved in CSS. Blanc et al.18 found similar results in 30 patients without known carotid sinus hypersensitivity or syncope. Abnormal sternocleidomastoid electromyograms were associated with abnormal responses to CSM. Because the denervated sternocleidomastoid muscle cannot provide or contribute information to the central nervous system baroreflex centers, any output from the carotid sinus is inappropriately interpreted as increased blood pressure.

Other Therapies

When CSS is the likely cause of syncopal episodes, the initial treatment recommendation should be simple elimination of any recognized maneuvers that may precipitate an event. Discontinuation of wearing tight collars and ties and shaving more carefully may help. Hypovolemia should be corrected. The addition of high salt intake, volume expanders such as fludrocortisone acetate (Florinef),19 or oral vasopressors such as midodrine (ProAmatine) may be helpful, but these interventions are frequently limited in older patients by comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, heart failure).

In the pre–pacemaker era, recalcitrant cases of carotid sinus syncope were treated with carotid sinus denervation by surgical technique.20 Surgical sinus denervation currently is reserved for cases secondary to head or neck tumors or lymphadenopathy, or it is performed in conjunction with carotid endarterectomy or in patients with severe refractory carotid sinus syncope of the purely vasodepressor type.

Evidence of Clinical Benefit

Observational Studies

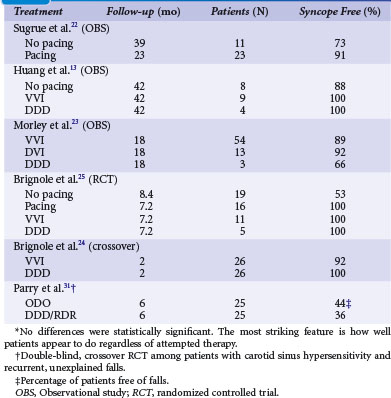

Table 15-2 summarizes studies of pacing for CSS.13,21–25 Earlier studies tended to be retrospective reports of pacing practices for CSS and therefore were inherently biased toward patients with a clear diagnosis of CSS who would truly benefit from pacing.

Randomized Trials

More recently, prospective, randomized trials have examined outcomes on the basis of presence of pacing and mode. A prospective, randomized Italian trial reaffirmed the important role of permanent pacing; 60 patients with CSS were randomized to pacing (32) or no pacing (28) therapy.14 During a follow-up of about 3 years, syncope recurred in 16 patients of the no-pacing group (51%) and in three (9%) of the pacing group (P = .002). This finding somewhat confirms the usefulness of pacing for the prevention of carotid sinus syncope, although potent placebo effects cannot be ruled out (see later).

Falls

Pacing of patients with CSS has been associated with a reduction in falls.26 Furthermore, among patients with unexplained and recurrent falls, carotid sinus hypersensitivity may be an important risk factor.27,28 In 2001, Kenny et al.29 reported the open-label SAFE PACE trial, designed to determine whether cardiac pacing reduces falls in older patients with unexplained falls and a cardioinhibitory response to CSM. The 187 patients were randomized to receive a dual-chamber pacemaker, with rate-drop responsiveness, or no intervention. Patients who received a pacemaker had a highly significant 58% reduction in falls and a 40% reduction in syncope. Although these results suggest that many unexplained falls in the elderly are caused by carotid sinus syncope, and that these can be prevented with pacing, one must remember that this was an open-label trial.

In 2010, Ryan et al.30 reported the SAFEPACE-2 study, in which 141 older patients with unexplained falls and cardioinhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity were randomized to receive a rate-drop responsive dual-chamber pacemaker or an implantable loop recorder (ILR). Although the relative risk (RR) of reporting a fall after implantation of a device decreased (0.23; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.15 to 0.37), there were no significant differences in falls reported between the paced group (67%) and the ILR group (53%) (difference RR = 1.25; 95% CI = 0.93 to 1.67). These results are at odds with the findings in SAFE PACE; possibly because of differences in patient population (patients were older and frailer). Furthermore, due to recruitment difficulties, SAFEPACE-2 may have been underpowered; according to sample size calculations, 226 patients were needed to detect a 20% difference with 80% power.

Only one double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial has reported pacing in patients with recurrent, unexplained falls and carotid sinus hypersensitivity.31 All study participants received a dual-chamber pacemaker with rate-drop response programmer and were randomized to DDD/RDR mode (on) versus ODO mode (off); after 6 months, patients switched to the opposite mode. Only 25 of the 34 recruited patients completed the study. The total number of falls decreased after pacemaker implantation, but risk of falling with the pacemaker on versus off was not statistically significant (RR = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.62 to 1.10). Although this suggests a placebo effect, similar to that seen in pacing of vasovagal syncope patients, the results must be interpreted with caution; the study was underpowered because of an unexpectedly high attrition rate of 26%.

Patient Selection

Careful patient selection may help provide effective and efficient therapy for CSS. Permanent pacemaker therapy is indicated for patients with recurrent, frequent, or severe CSS, particularly for predominant cardioinhibitory syncope.32,33 Predictors of success with permanent pacing include multiple episodes before implantation; episodes that occur while upright or sitting; and episodes preceded by a recognized stimulus.34 Syncope recurrence after implantation of a permanent pacemaker may be caused by a prominent vasodepressor component.

Physical Diagnosis with Carotid Sinus Massage

The carotid sinus is located high in the neck below the angle of the mandible. Carotid massage is contraindicated in the presence of bruits or a history of cerebrovascular disease, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), or endarterectomy. Sequential application of CSM to the left and right carotid arteries should be performed with at least 10 to 20 seconds between applications. The duration of carotid massage should be 5 to 10 seconds, and it should be terminated with the onset of characteristic asystole or severe presyncope. In most series, the predominant responses to CSM were obtained on the right side.5 CSM should be performed while the patient is both supine and upright, either sitting or while secured safely on a tilt table. It may be difficult to document transient hypotension with standard sphygmomanometric methods, and noninvasive continuous digital plethysmography is often used.

Physiologic Responses

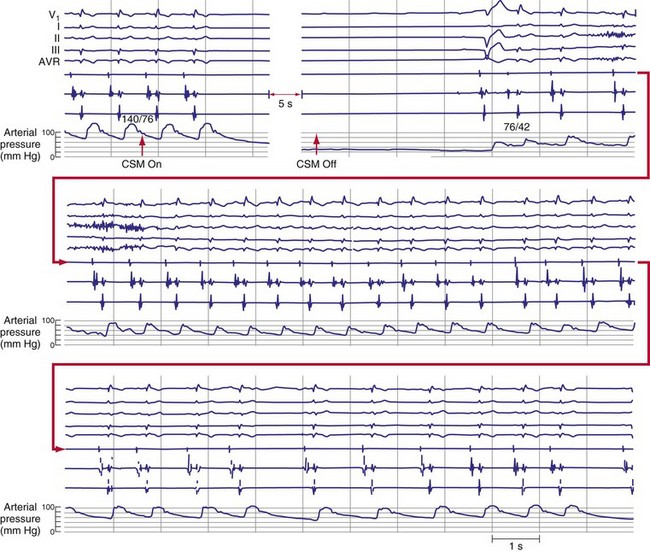

Carotid sinus massage elicits both cardioinhibitory and vasodepressor responses (Fig. 15-1). A cardioinhibitory response to CSM is defined as 3 seconds or longer of ventricular standstill or asystole. Ventricular asystole usually results from a sinus pause caused by sinus node exit block,35 but it can result from atrioventricular (AV) block as well. A vasodepressor response to CSM is defined as a drop in systolic blood pressure of 50 mm Hg or more during massage; this may be difficult to demonstrate in patients who have a significant cardioinhibitory component. In contrast to the induced cardioinhibitory component of carotid sinus hypersensitivity, the vasodepressor response may have a slower, more insidious onset and a more prolonged resolution.

Carotid Sinus Hypersensitivity and Carotid Sinus Syncope

Carotid sinus hypersensitivity denotes abnormal physiologic responses to CSM, either cardioinhibitory or vasodepressor (or both). The presence of asymptomatic carotid sinus hypersensitivity is quite common in older adults. For example, a positive cardioinhibitory response to CSM was noted in 32% of patients undergoing coronary angiography.36 CSS is the syndrome of syncope in association with carotid sinus hypersensitivity, and in the absence of other apparent causes of syncope.

Complications

Carotid sinus massage is safe if done carefully. CSM is contraindicated in patients with a history of cerebrovascular disease or carotid bruits, because it can cause cerebrovascular accident (CVA, stroke). In a review of 3100 episodes of CSM performed on 1600 patients, the seven complications (0.14%) were neurologic and transient.37 In another review of CSM on 4000 patients, complications were observed in 11 patients (0.28%);38 all were neurologic. After 1 month, nine patients had made a full recovery; neurologic symptoms persisted in two patients. Rare, arrhythmic complications include asystole and ventricular fibrillation.39

Programming

Pacing in AAI mode is contraindicated because many patients may eventually demonstrate associated reflex AV block.40 In general, patients appear to benefit most from AV sequential pacing, even when a significant component of vasodepressor CSS is present. VVI pacing should not be used in patients with intact ventriculoatrial (VA) conduction,41 because of possible pacemaker syndrome. Lack of VA conduction at a given time, however, does not ensure against its future development. Therefore, we recommend dual-chamber pacemakers for patients with CSS and normal sinus rhythm.

Few studies have examined the role of rate-responsive pacing in CSS. Patients are generally older and therefore may have bradycardic comorbidities such as sick sinus syndrome or chronotropic incompetence, either intrinsic or pharmacologic. Therefore, rate-responsive pacing might be beneficial. Similarly, few studies have prospectively examined pacing with rate-drop or hysteresis capabilities, which has the theoretical advantage of providing rapid, higher-rate AV sequential pacing to counteract the vasodepressor component during CSS attacks.42

Vasovagal Syncope

Vasovagal Syncope

Clinical Perspective

Vasovagal syncope is the most common of the neurally mediated syncopal syndromes. Most people who faint probably do not seek medical attention for isolated events.2 Prolonged standing, sight of blood, pain, and fear are common precipitating stimuli for this, the common faint. Patients develop nausea, diaphoresis, pallor, and loss of consciousness from hypotension with or without significant bradycardia. Return to consciousness typically occurs after seconds or 1 to 2 minutes. Those with adequate warning may be able to use physical counterpressure maneuvers, or simply sit or lie down, to prevent a full faint. However, some patients have little or no prodrome, no recognized precipitating stimulus, or marked bradycardia accompanying the faint.43–47 These patients have sparked interest in permanent pacing as a therapy.

Epidemiology

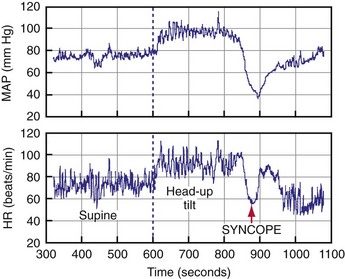

About 40% of people faint at least once in their life, and at least 20% of adults faint more than once.48,49 Fainters usually present first in their teenage years and 20s and may faint sporadically for decades. This long, usually benign, and sporadic history can make for difficult decisions about therapy. Syncope is responsible for 1% to 6% of emergency room visits and 1% to 3% of hospital admissions.50–52 Tilt tests are often used as a diagnostic tool, although they are limited by difficulties with sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility, and with little evidence-based agreement on methodologic details and outcome criteria. Positive tilt tests are characterized by presyncope, syncope, bradycardia, and hypotension, as well as a reproduction of the patient’s perisyncopal symptoms53,54 (Fig. 15-2).

Symptom Burden and Quality of Life

The vasovagal syncope syndrome has an extremely wide range of symptoms. The symptom burden varies from a single syncopal spell in a lifetime to daily faints. Some patients have very sporadic presentations, with periods of intense symptoms interspersed with long periods of quiescence. Other patients faint at more regular intervals, although they may be months or years apart. Several observational studies and randomized clinical trials reported that patients have a median of 5 to 15 syncopal spells, with fainting episodes occurring over 2 to 60 years.55–58 Patients with recurrent syncope are impaired similar to those with severe rheumatoid arthritis or chronic low back pain and psychiatric inpatients.55 The quality of life decreases as the frequency of syncopal spells increases.56

After clinical assessment, many patients continue to do poorly. After 1, 2, and 3 years, 28%, 38%, and 49% of patients faint again, respectively.59 Interestingly, several groups reported a 90% reduction in the total number of faints in this patient population after the tilt test. The reason for this apparently great reduction in syncope frequency after assessment is unknown, but it does lead to a large number of patients who request further treatment. Therefore, when assessing syncope patients, clinicians need to be alert to the surprising impairment of quality of life that many patients endure, to provide a perspective that lasts decades, and to remember that the patient’s clinical state will probably fluctuate.

Rationale for Pacing

Table 15-3 lists recommendations and other considerations in pacing for vasovagal syncope.

TABLE 15-3 Summary of Pacing for Vasovagal Syncope

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Goal | Prevent reflex bradycardia and compensate for reflex hypotension |

| Prevent syncope | |

| Level of evidence for success | Limited evidence for benefit based on double-blind RCTs |

| May be a subset of patients with proved bradycardia who benefit | |

| Consensus recommendations | Class IIa: Recurrent vasovagal syncope with clinically documented bradycardia, or bradycardia induced on tilt test |

| Patient selection | Medically refractory, frequent, disabling vasovagal syncope |

| Documented pauses during syncope | |

| Tilt test results not helpful | |

| Programming considerations | Dual-chamber pacemaker |

| Benefit from specific sensor to drive rate-response or pacing algorithm (rate-drop response, ventricular impedance) not proved |

Physiology

Syncope is a transient loss of neurologic function caused by a global reduction of cerebral blood flow (CBF). Sudden cessation of CBF results in loss of consciousness within 4 to 10 seconds.60 Lesser CBF reductions may result in presyncope. Almost all vasovagal syncope occurs while the patient is in an upright position. Syncope is usually associated with heightened physiologic or psychological stress, such as prolonged orthostatic stress; arising quickly and walking; pain, fear, emotion, or seeing blood or medical procedures; and strenuous exercise.

Evidence for Bradycardia

Tilt-Table Tests

Bradycardia frequently occurs during vasovagal syncope induced by tilt-table testing.61,62 The mean heart rate during syncope induced by passive head-up tilt tests is 30 beats/min (bpm), and asystole longer than 3 seconds is often documented. However, uncertainty surrounds the relationship between the hemodynamics of tilt testing and clinical vasovagal syncope. For example, the ISSUE investigators found no relationship between the heart rate during syncope on tilt testing and during syncope in the community population. Patients with tilt test–induced bradycardia frequently do not have bradycardia during clinical syncope.63,64 Therefore, although bradycardia is the rule rather than the exception during a positive tilt test, the bradycardia evoked on a tilt test may not resemble the hemodynamics during syncope in that patient in the community.

Pacemaker Memory

Is asystole in patients in the community frequently associated with syncope? Evaluation of frequent fainters with pacemakers programmed to act as event recorders demonstrated that while transient asystole is common during documented syncope, many other asymptomatic asystolic episodes also occurred. Only 0.7% of asystolic events lasting 3 to 6 seconds and 43% of events lasting longer than 6 seconds resulted in symptoms of presyncope or syncope.65 Therefore, even asystole of several seconds’ duration does not necessarily cause syncope.

Implantable Recorders

The ILR permits prolonged electrocardiographic monitoring and is a reasonable approach to diagnosing patients with infrequent syncope. Current ILRs weigh only 17 grams and have battery life of 14 months. The ECG signal is stored in a buffer that can be frozen with a manual activator. The ILR has programmable, automatic detection parameters for high and low rates and pause. In a Canadian study of 206 patients, symptoms recurred in 69% of patients. Bradycardia was detected more frequently than tachycardia (17% vs. 6%).66,67

The European International Study on Syncope of Uncertain Aetiology (ISSUE) enrolled 111 patients with syncope and previous tilt-table testing; not all tilt tests were positive.68 Patients with positive or with negative tilt tests both had events in 34% of each group over a follow-up of 3 to 15 months. Marked sinus bradycardia (46%) or asystole (62%) were detected during syncope. Therefore, bradycardia reported during syncope varies widely; 17% to 62% of patients with vasovagal syncope had significant bradycardia during syncope in the ILR studies. The heart rate response during tilt testing did not predict spontaneous heart rate response, with more frequent asystole than expected based on tilt response. Thus, many patients with positive tilt tests may develop some degree of bradycardia at presyncope or syncope, and pacing may be a plausible treatment.

Conservative Therapy

Pacing should be tried only in patients with vasovagal syncope who have not responded to, or who are not candidates for, other treatments. Currently, most clinicians first teach patients about the causes of syncope, encourage fluid and salt intake, and coach physical counterpressure maneuvers. If this initial approach is unsuccessful, pharmacologic therapy is used (fludrocortisone, midodrine, β-blockers, SSRIs). Only after these options have been explored should permanent pacing be considered (Table 15-4).

TABLE 15-4 Principles of Management of Vasovagal Syncope

| Area | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis and prognosis | Confirm diagnosis with history, tilt-table tests, and loop recorder. |

| Assess likelihood of syncope recurrence (>2 spells or recent worsening). | |

| Assessment of patient needs | Insight into diagnosis |

| Cause of syncope | |

| Probability of syncope recurrences | |

| Treatment options | |

| Conservative advice | Maximizing salt and fluid intake |

| Physical counterpressure maneuvers | |

| Driving and reporting to authorities | |

| Avoidance and management of triggers | |

| Medical options | Fludrocortisone (weak evidence) |

| Midodrine (good evidence) | |

| Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (weak evidence) | |

| β-Blockers in patients age >42 (modest evidence) | |

| Permanent pacing | Weak evidence |

Salt and Fluids

Blood volume is an important factor in the pathophysiology of vasovagal syncope. Syncope almost only occurs in the upright position, and many patients faint only from orthostatic stress in situations such as attending religious services, parades, or outdoor events and taking showers. Prolonged drug-free head-up tilt provokes syncope in a large number of syncope patients; this depends on the duration and angle of head-up tilt.69 Finally, many patients report avoiding dietary salt and have low daily urinary sodium excretion.70

Physical Counterpressure Maneuvers

Physical counterpressure maneuvers may be quite helpful, although no blinded, controlled studies have been reported. Patients must have a prodrome long enough that they can react by isometrically tightening muscles using maneuvers such as squatting, leg crossing, and fist clenching. Van Dijk et al.71

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree