Chapter 41 Overview of Vasculitis

The vasculitides are a group of rare diseases linked by the pathological consequences of vascular inflammation, including bleeding, ischemia, and infarction of downstream organs (Box 41-1). However, the clinical spectrum of these diseases is wide ranging and includes a myriad of clinical and pathological findings. Not all disease phenotypes that occur in the vasculitides are due to true “vasculitis” (i.e., inflammation of vascular structures). Some damage in vasculitis is due to nonvascular inflammation. For example, arthritis, uveitis, and pulmonary nodules are parts of different vasculitides but are not due to interruption of vascular flow. The pathophysiology of vasculitis is covered in Chapter 9 and in individual chapters on Takayasu’s arteritis (TA) (Chapter 42), giant cell arteritis (GCA; Chapter 43), and Kawasaki disease (Chapter 45).

![]() Box 41-1 Classification of Vasculitis*by Predominant Size of Vessel Involvement

Box 41-1 Classification of Vasculitis*by Predominant Size of Vessel Involvement

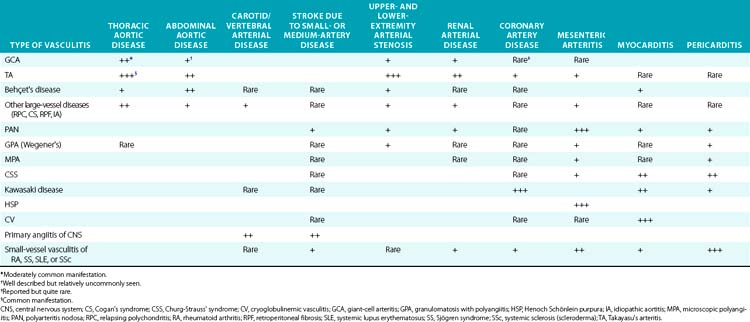

This chapter reviews the major types of vasculitis, discusses evaluation of suspected cases of vasculitis, and outlines approaches to treatment and management of these disorders. There is a focus on differentiating inflammatory from noninflammatory disease as it relates to the types of patients physicians specializing in vascular medicine are likely to encounter in a consultative practice (Table 41-1). The newest advances in diagnosis and treatment are also reviewed briefly.

Classification of Vasculitis

Two major classification systems for vasculitis exist: the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) system1 and the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference definitions.2 These systems were not meant to be strictly diagnostic systems, but rather classification systems. These are definitions to apply to established vasculitis and differentiate one vasculitis from another. The main use of these systems has been for clinical trials and other types of clinical research. Nevertheless, these systems have been adapted for use by clinicians as helpful guides to practice. Not all types of vasculitis are included in the ACR or Chapel Hill systems; both are currently undergoing reevaluation and revision.3

Perhaps the simplest method of sorting out the vasculitides, albeit also incomplete and not fully accurate, is to list them according to the size of artery (predominantly but not necessarily exclusively) involved (see Box 41-1). This results in considering small-vessel, medium-vessel, and large-vessel vasculitides. This system, although not applied for clinical trials or even clinically for treatment purposes, is an easy one to use as a first approach to describing the diseases and their major manifestations, and is used to outline the descriptions of the vasculitides in this chapter. However, when specific diseases and results of treatment trials are mentioned, the ACR and Chapel Hill Consensus systems are applied.

Large-Vessel Vasculitis

The large-vessel vasculitides are disorders in which the aorta and its main branches are affected, including the subclavian, carotid, vertebral, renal, mesenteric, and iliac arteries4 (Fig. 41-1). Because such vessels are so frequently involved in noninflammatory vascular diseases, and patients with these diseases are frequently encountered by specialists in vascular medicine, these disorders are particularly highlighted in this textbook. Also included are individual chapters on TA (Chapter 42), giant cell (temporal) arteritis (Chapter 43), and Kawasaki disease (Chapter 45). The vasculitides involving large arteries are briefly described in this section, but it is important to realize that many of them also involve smaller-sized vessels.

Giant Cell Arteritis

Giant-cell arteritis, also commonly known as temporal arteritis and described in detail in Chapter 43, is the most common of the idiopathic vasculitides.4,5 Giant-cell arteritis affects men and women aged 50 and older but is especially prevalent after age 70. Many vascular and systemic manifestations are seen in this disease. Vascular disease occurs in the aorta and its branches, with predilection for the branches of the carotid arteries, especially the ophthalmic artery, with resulting headaches, jaw claudication, and visual impairment. Rapid-onset irreversible monocular blindness is the most feared complication, but stroke, limb ischemia, and aortic disease can occur, the latter more common than generally appreciated, especially several years after the initial presentation. Common systemic manifestations include fever, anemia, proximal arthralgias (polymyalgia rheumatica), and fatigue. Diagnosis is often established on finding arteritis on temporal artery biopsy, but this is not required for a diagnosis. Elevated acute phase reactants are seen in 90% of cases. Treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids is highly effective but often results in significant drug-related morbidity.

Takayasu’s Arteritis

Takayasu’s arteritis, described in detail in Chapter 42, is a vasculitis that involves the aorta and all its major branches and the pulmonary arteries, including but not limited to the brachiocephalic, carotid, vertebral, subclavian, renal, femoral, and coronary arteries. This disease often results in stenoses, occlusions, and ischemic damage to end organs and limbs.4,6 Stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), limb claudication, and severe renovascular hypertension are all complications well known to occur in this disease. It is mostly seen in women and usually first presents clinically in the second or third decade, but it can occur at older ages. Many patients have associated systemic symptoms of fever, arthralgias, and malaise. The disease has a waxing and waning course, and delay in diagnosis is common. Treatment involves glucocorticoids in almost all patients and often the addition of immunosuppressive medications. Surgical bypass procedures may be necessary in some cases.

Behçet’s Disease

Behçet’s disease is a systemic inflammatory disease with multiple mucocutaneous manifestations, especially including genital and oral ulcers and often severe sight-threatening inflammatory eye disease.7 Arthritis, gastrointestinal disease (including mucosal lesions), epididymitis, and secondary amyloidosis can also occur. Although its prevalence is markedly increased in countries in the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East, and East Asia and descendents of people from these regions, Behçet’s disease is found in populations worldwide.

Relapsing Polychondritis

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare connective tissue disease that predominantly affects the cartilaginous structures of the eyes, ears, nose, and subglottis/trachea, but may also affect a wide variety of other organ systems and is associated with vasculitis, especially of large vessels.8 The cardinal feature of polychondritis is auriculitis, inflammation of the outer ear, usually sparing the noncartilaginous lobe. Auriculitis, which is also a feature of GPA and CSS but virtually of no other diseases, is readily treated with glucocorticoids and can result in disfigurement if allowed to go untreated. Other common manifestations include inflammatory eye disease that can lead to blindness, destruction of nasal cartilage leading to internal derangement and external disfigurement, sensorineural hearing loss and vertigo, arthritis, and subglottic inflammation with resulting stenosis, a life-threatening condition. Each of these features can also be seen in GPA, although auriculitis is rare in this disease, and relapsing polychondritis is not associated with parenchymal pulmonary manifestations.

Cogan’s Syndrome

Cogan’s syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by inflammatory eye and inner ear/vestibular disease that can also involve inflammatory vasculitis.9 It is a disease of young adults, usually first affecting patients before age 40, although both children and older patients have also been affected.

Idiopathic Aortitis

Aortitis may be found in the absence of any other manifestations of a systemic inflammatory disease.10–12 These cases often come to the attention of vascular medicine specialists when patients undergoing surgical repair of aortic aneurysms and dissections are found to have inflammation consistent with aortitis on pathological specimens. Autopsies and studies of large numbers of surgical specimens have demonstrated that noninfectious aortitis occurs in 4% to 15% of cases. Although on detailed investigation, many of these patients are retrospectively found to have had evidence of GCA, TA, relapsing polychondritis, GPA, or another definable vasculitis, it is common among these cases to find no evidence of more systemic inflammatory disease. The majority of cases of so-called idiopathic aortitis involve thoracic lesions, in contrast to the overall predominance of abdominal aortic lesions for noninflammatory disease.

The approach to treatment of idiopathic aortitis is unclear; many patients never develop other findings of vasculitis. However, new aneurysms and significant vascular disease do occur in some cases.11 Comprehensive evaluation of evidence of systemic disease is necessary and should include a detailed physical examination, diagnostic imaging, laboratory studies, and other approaches outlined later in this chapter. Appropriate treatment should be given if inflammatory disease other than that seen in the surgical specimen is found, but not all patients require glucocorticoids, especially in the postoperative period. Furthermore, regular follow-up of such patients by a specialist knowledgeable about vasculitis is imperative because lesions may develop subtly and only years after the initial pathological diagnosis is made.

Medium-Vessel Vasculitis

Polyarteritis Nodosa

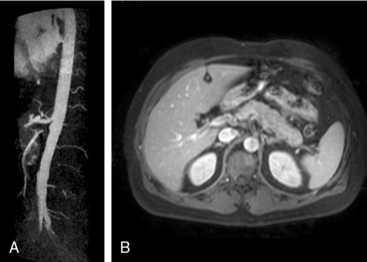

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is among the “purer” vasculitides in that most of its manifestations are due to true vascular inflammation.13 With the identification of other types of vasculitis, the spectrum of what is now diagnosed as PAN has narrowed over the past 50 years. Although characterized as a medium-vessel disease, PAN may also involve small vessels such as those in the skin. Polyarteritis nodosa frequently involves inflammation leading to multiple small aneurysms that often appear angiographically as a “string of beads.” Ischemia and infarction of kidneys, intestines, and skin are common in PAN, with arthralgias, myalgias, and fevers also frequently seen. Diagnosis is based on angiographic appearance (Fig. 41-2) or tissue pathology, often from surgical specimens such as a resected ischemic bowel segment. Interestingly, PAN in one subset of patients is associated with either hepatitis B or hepatitis C infections.13,14 Importantly, there is a difference between hepatitis C–associated PAN and hepatitis C–associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (CV, see later section). Cardiac manifestations of PAN are due to coronary arteritis or malignant hypertension (secondary to renal artery disease) and include myocardial ischemia, heart failure, and arrhythmias.

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (Wegener’s)

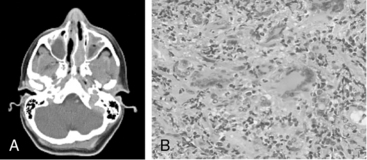

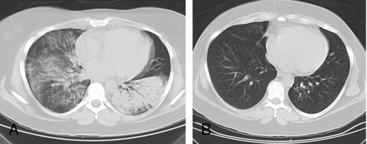

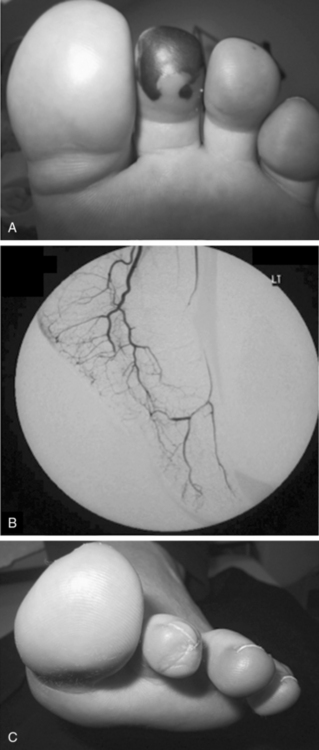

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is characterized by the triad of inflammation and destruction of tissue in the upper airway and sinuses (Fig. 41-3), lower airway (Fig. 41-4), and kidneys (Fig. 41-5), as well as the development of ANCAs.15,16 Approximately 70% of patients with GPA are positive for ANCA at diagnosis, although some will develop the antibodies later in the course of their illness. Among patients with GPA and glomerulonephritis, more than 90% are positive for ANCA. Although the combination of these features is common in GPA, many patients present with only a subset of these findings. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis also frequently involves many other organ systems. The upper airway lesions include destructive rhinitis, often leading to nasal bridge collapse and the “saddle nose” deformity, sinusitis, and subglottic inflammation that can lead to life-threatening tracheal stenosis. The most severe form of pulmonary disease in GPA is alveolar hemorrhage, and this is a common cause of early death. Other common pulmonary lesions include nodules, with or without cavitation, and tracheobronchitis. Other common features of GPA are retroorbital pseudotumor with resulting proptosis, conductive and sensorineural hearing loss, mononeuritis multiplex, arthritis, and purpura. Peripheral vascular involvement with gangrene is seen in GPA and may be the presenting feature (Fig. 41-6).

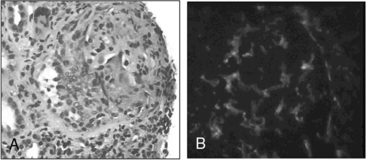

Figure 41-5 (See also Color Plate 41-5.) Renal biopsy in a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; Wegener’s same patient as in Fig. 41-4) with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

Venous thromboses, including both deep vein thromboses (DVTs) and pulmonary emboli (PEs), occur frequently in GPA and may be associated with active disease.17,18 Although some of the pathology in GPA is indeed granulomatous with histiocytes, piecemeal necrosis, and occasional giant cells and eosinophils, other manifestations of inflammation are also seen in the disease. True vasculitis occurs and includes capillaritis. The renal disease of GPA is identical to other ANCA-positive diseases, and the pathology is that of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

Untreated, GPA most often leads to death or serious damage.19 Glucocorticoids are always used for treatment, but the prognosis of GPA changed considerably when a protocol using cyclophosphamide was introduced in the 1970s at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The morbidity and mortality of GPA was markedly improved by cytotoxic therapy: 1-year mortality changed from more than 80% to less than 20%.16,19,20 However, serious side effects are common with the use of cyclophosphamide, and the rate of recurrent disease in GPA after therapy is above 50%. In recent years, new treatment protocols have been tested in open and controlled trials that incorporate less toxic immunosuppressive drugs, including methotrexate and azathioprine.21–23 Two multicentered randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that treatment with rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 receptor on B cells, was equivalent to cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in ANCA-associated vasculitis (GPA and MPA).24,25 In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved rituximab for the treatment of GPA and MPA, and it has quickly become an established alternative to cyclophosphamide.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree