Fig. 13.1

Clinical features of DYNC2H1 patients. (a–e) Hallmarks of Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy (JATD): (a, JATD-5; b, JATD-16) Small thorax due to short ribs; (a, JATD-5, b, JATD-16, c, JATD-5, d, JATD-14) Small ilia with acetabular spurs; (c, JATD-5, d, JATD-14) Shortening of femurs, accompanied by bowing in (d, JATD-14); (e) 3D reconstruction of CT images of patient JATD-4. (f–i) Severity of the rib shortening varies between different patients from different families carrying DYNC2H1 mutations as well as between affected siblings: while patient JATD-5 presents with extremely shortened ribs (f), patient JATD-18 (UCL62.2) is only mildly affected (g). (h, i) Patient JATD-14 (h, UCL80.1) is markably more severely affected than his sister JATD-14 (i, UCL80.2). (j–l) Additional features: (j) scoliosis in JATD-2, (k) syndactyly in JATD-2, (l) ear malformation in JATD-16. (m–q) Thoracic narrowing becomes less pronounced with increasing patient age. (m) Shows patient JATD-16 at under 5 years; the same patient is shown a few years later in (n) at under 10 years. (o) Patient JATD-3 in his 20s, (p) patient JATD-2 in his late teens, (q) patient JATD-1 in his mid-20s these cases have less pronounced thoracic phenotypes compared to birth or infancy, as described in the text. Note also that shortening of the upper limbs seems less severe when JATD patients reach adolescence (With permission from Schmidts et al. [15])

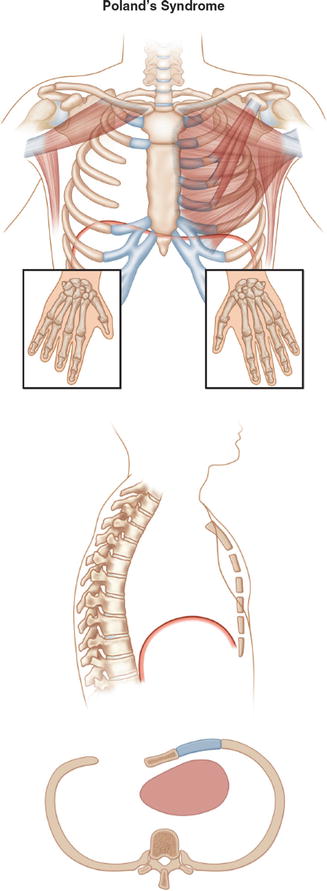

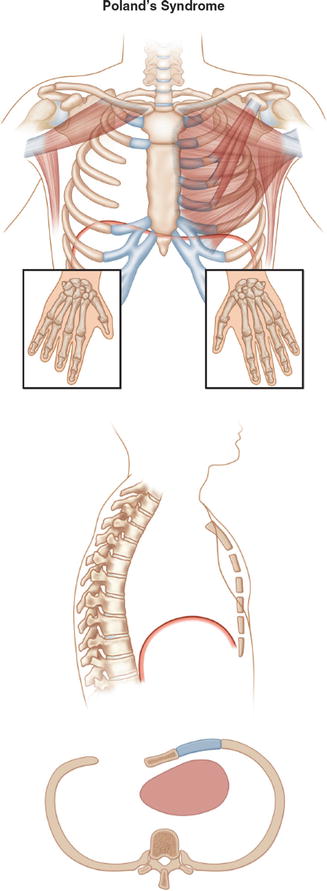

Poland Syndrome

Poland syndrome (PS) is classified as a chondrocostal chest wall deformity with main clinical manifestation the underdevelopment or absence of the major pectorals muscle (Fig. 13.2). It was Alfred Poland a British surgeon at Guys Hospital in 1840 that reported the partial absence of major pectoralis muscle in cadavers and ipsilateral deformity of the hand in the same cadaver but without associating these two anomalies [19]. Crarkson a plastic and hand surgeon almost 100 years later in 1962 and in the same hospital reported the association of these two anomalies and gave Poland s syndrome identity [20]. The etiology still remains unknown and only few theories have been reported in the literature. The most accredited hypothesis is the interruption of the vascular supply in subclavian and vertebral artery during embryonic life that leads to different malformations [21]. Another theory includes paradominant inheritance or the presence of a lethal gene survival by mosaicism [22]. Poland syndrome is a congenital unilateral chest wall deformity that affects both males and females with aeration of 3:1 and with an incident variation from 1–7,0000 to 1–10,0000 live births [23]. Patients with PS are usually a symptomatic and there is no limitation due to muscle defects. Key features for the diagnosis of Poland syndrome include partial or complete absence of the pectoralis major muscle and associated breast deformity. The breast anomaly ranges from mild asymmetry of shape and size including the nipple complex to severe hypoplasia or aphasia including atheling or polythelia. Upper limb is usually involved from the classical symbrachydactily to split hand or other defects [24, 25]. Cardiac and renal anomalies have also been reported as well as dextroposition [26] and scoliosis [27]. Finally other chest wall deformities can co-exist with pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum.

Fig. 13.2

Poland’s syndrome

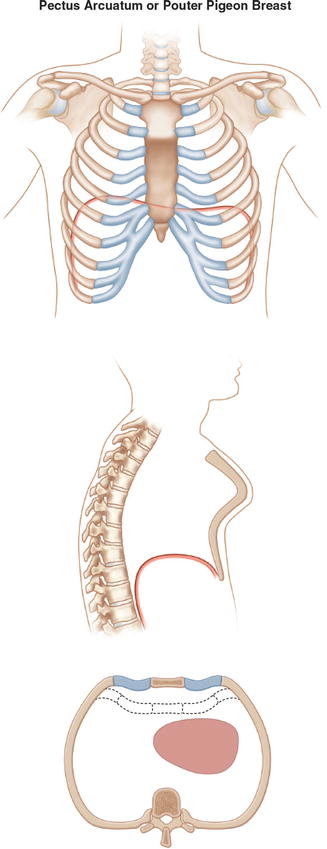

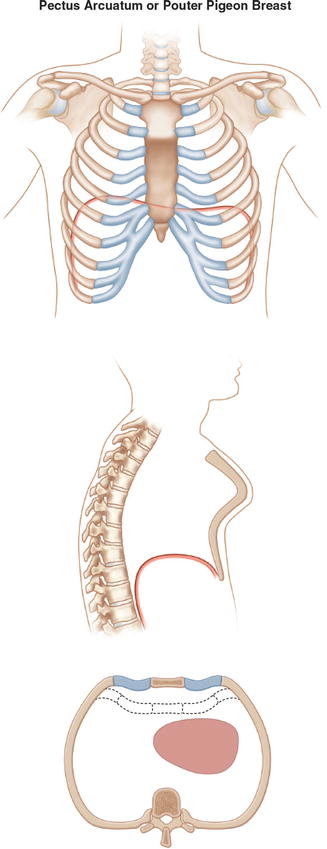

Pectus Arcuatum

Pectus arcuatum represents a rare category of chest wall deformities in the family of pectus anomalies and is derived from the latin word arcus meaning an arch or curvature (Fig. 13.3). It includes mixed excavatum and carinatum features along a longitudinal or transversal axis resulting in a multiplanar curvature of the sternum and adjacent ribs [28]. This clinical condition usually coexists with Poland syndrome and it has been correlated with cardiac abnormalities such as ventricular septum defect [29].

Fig. 13.3

Pectus arcuatum or Pouter pigeon breast

Sternal Anomalies – Sternal Cleft

Sternal cleft represents a rare idiopathic chest wall deformity caused by a defect in the sternum’s fusion process (Fig. 13.4). It accounts for 0.15 % of all chest wall deformities [30] and there is an a association with the Hexb gene [31]. According to the classification proposed by Schamberger and Welch in 1990 there are four types of sternal clefts [32]:

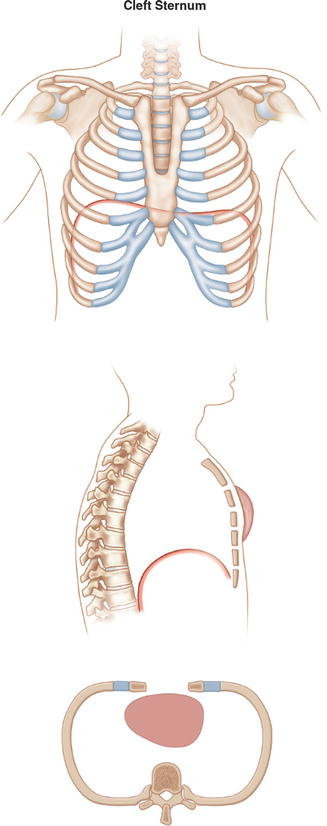

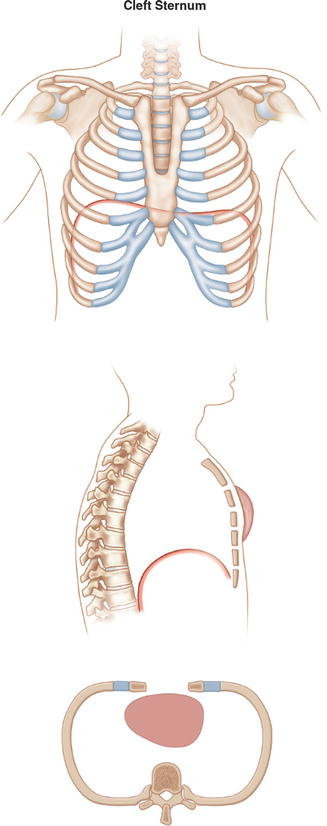

Fig. 13.4

Cleft sternum

Thoracic ectopic cordis. The heart is ectopic and not covered by skin. The chest cavity is hypo plastic and is associated with very poor prognosis and with only few survivals following surgical intervention [33].

Cervical ectopia cordis. More rare case than the above mentioned. The heart is more cranial, sometimes with the apex fused with the mouth. Prognosis is always negative.

Thoracoabdominal ectopia cordis. The heart is covered by a thin membranous layer and is associated with an inferior sternal defect. It usually presents as part of pentalogy of Cantrell [34] and the prognosis after repair can be good.

Sternum cleft- bifid sternum. It can be partial or complete as a result of deficiency in the midline embryonic fusion of the sternal valves [35].

Sternal clefts can be classified as complete, superior or inferior. Superior clefts can be U shaped if proximal to the fourth cartilage or V shaped if reaches the xiphoid process (Fig. 13.5). Before planning a surgical intervention other defects should be identified [36] and ruled out such as cardiac, aortic coarctation, eye abnormalities, hemangiomas, cleft lip or palate and gastroschisis.

Fig. 13.5

Classification of sternal clefts. I Main types. (a) Superior sternal cleft. (b) Subtotal sternal cleft. (c) Total sternal cleft. (d) Inferior sternal cleft. II Rare types. (e) Superior sternal cleft with cleft mandible. (f) Median sternal cleft

References

1.

Jeune M, Carron R, Beraud C, Loaec Y. Polychondrodystrophie avec blocage thoracique d’évolution fatale. Pediatrie. 1954;9(4):390–2.PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree