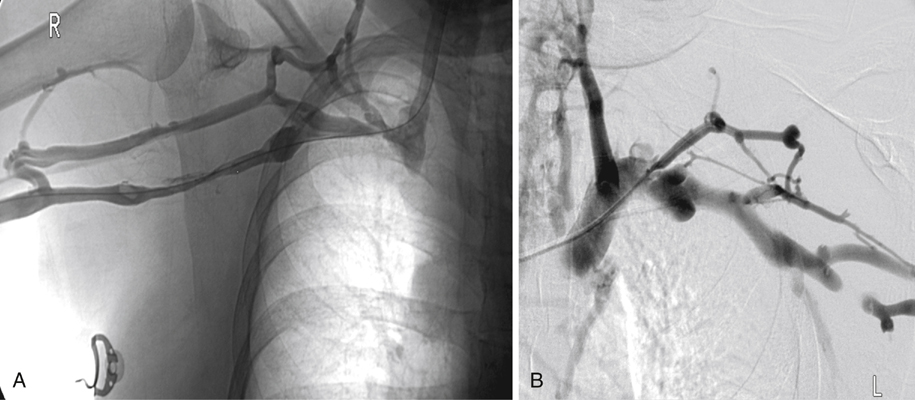

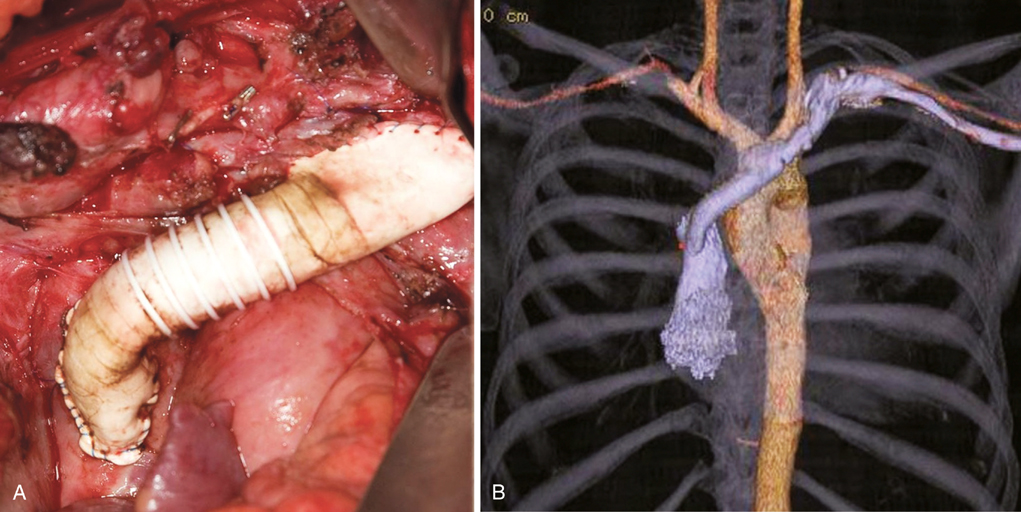

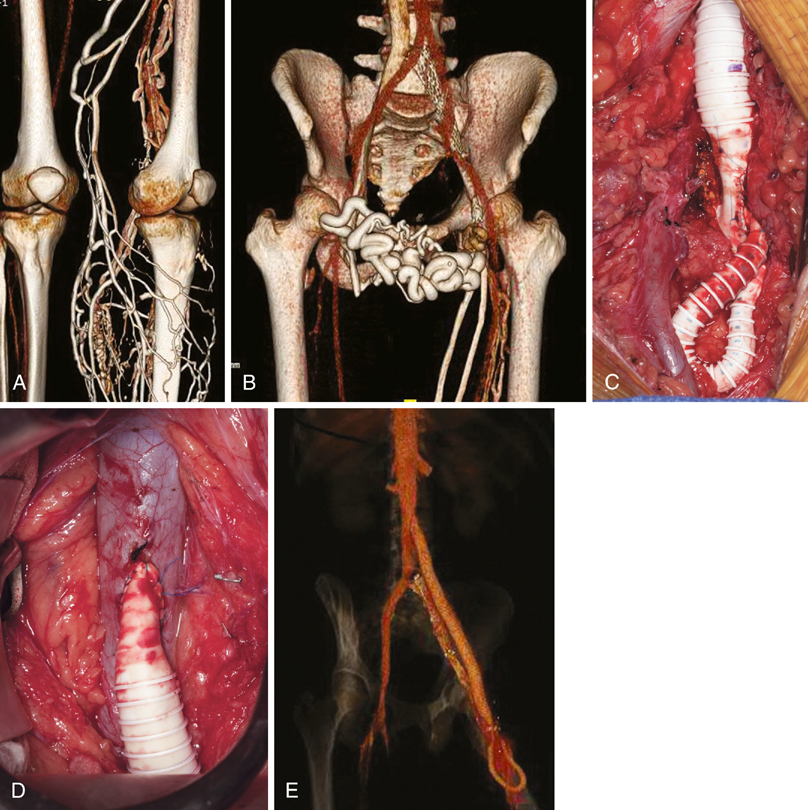

Patients with SVC occlusion come to the hospital with facial or arm swelling, head fullness, dyspnea or orthopnea, generalized headache, or dizziness (Figure 1). The severity of the disease can often be determined by the number of pillows the patient requires to sleep on because of the severe venous engorgement of the head and neck. The most common benign causes today are pacemaker wires, central intravenous lines, and dialysis catheters, although about half of those who undergo open surgical reconstruction have mediastinal fibrosis. These patients in general respond poorly to stenting and have a high rate of recurrent stenosis as a result of the severe calcification around the SVC. Patients who are not candidates for endovascular treatment or in whom previous attempts at thrombolysis or stenting have failed are considered for open surgical reconstruction. Partial or full median sternotomy gains access to the SVC and innominate veins. Spiral saphenous vein graft is the preferred graft material, although panel saphenous vein graft or femoral vein as conduit are also very good choices for autogenous reconstruction. If inflow is good and only a short graft is needed, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) is an excellent graft material (Figure 2). Cryopreserved or fresh allografts and autogenous or bovine pericardium have also been used with success. Reconstruction of flow from one internal jugular vein is usually all that is required, because collateral circulation of the head and neck is usually excellent. Externally supported ePTFE is used to avoid external compression of the graft if adequate autogenous conduit is not available or in patients with severe mediastinal fibrosis or a tight mediastinum, Extra-anatomic reconstruction using a jugular–femoral bypass with composite saphenous veins has occasionally been used in cancer patients or in others with high risk for median sternotomy. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have progressed tremendously since the turn of the century and provide excellent three-dimensional imaging of the venous system using venous phase contrast-enhanced imaging (Figure 3A and B). Both modalities are suitable to identify iliocaval, hepatic, pelvic, renal, or iliac venous obstruction. Contrast venography is routinely performed in patients during endovascular reconstruction, and it is often helpful before open repair (Figure 4A).

Open Surgical Treatment of Thrombotic Vena Cava Occlusion

Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

Clinical Presentation

Surgical Technique

Inferior Vena Cava Thrombosis

Clinical Presentation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine