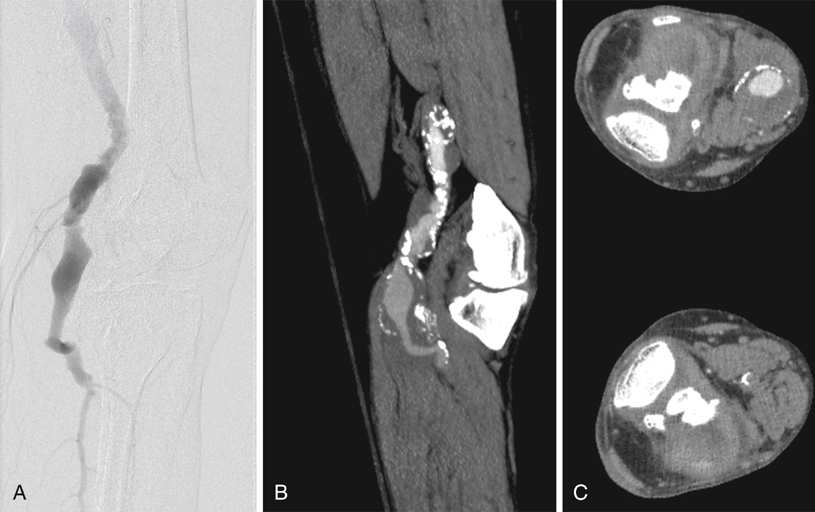

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) offer noninvasive ways to obtain information regarding the extent of the aneurysm and the status of runoff vessels. Images obtained through these modalities can be used to determine the best surgical approach for repair. CTA is especially useful if consideration is to be given to an endovascular repair. Conventional angiography provides only information about the internal diameter of a vessel and thus can underestimate the diameter of a PAA containing thrombus (Figure 1). The principal role of conventional angiography lies in its use for evaluating runoff vessels, particularly in the acute setting, and in initiating and follow-up imaging of thrombolysis. An analysis of the Swedvasc registry compared 1-year results between medial and posterior approaches. The medial approach was used just over 10 times more often than the posterior approach. Neither 30-day (93.0% vs. 93.9%) nor 1-year (87.0% vs. 90.3%) patency rates were statistically different between the posterior and the medial approaches, respectively (Table 1). The authors also found that these two approaches also had similarly low (3.7% vs. 2.6%) late amputation rates resulting from either of the two procedures. Some authors have offered dissenting opinions, with single-center data demonstrating superior patency and limb salvage with the posterior approach. TABLE 1 Patency Rates Comparing Medial and Posterior Approaches to Popliteal Artery Aneurysm Repair

Open Surgical Treatment of Popliteal Artery Aneurysms

Diagnosis and Imaging

Surgical Management

Repair

1-Year Patency (%)

Long-Term Patency

Author

Approach

Total

Sympt

Asympt

Vein

PTFE

30-Day

Patency (%)

P

PA

S

Years

P (%)

PA (%)

S (%)

Galland

Medial

28

12

16

20

8

100

ns

ns

ns

5

78∗

Kropman

Medial

33

20

13

24

9

100

93

96

96

4

69

78

90

Posterior

33

21

12

24

9

94

79

80

100

4

66

80

90

Ravn

Medial

390†

ns

ns

312

68

94

90∗

7

83∗,‡

Posterior

57†

ns

ns

38

19

93

87∗

7

82∗,‡

Zaraca

Medial

11†

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

6

100

100

91

Posterior

38†

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

6

94

97

97

Beseth

Posterior

30

28

2

0

30

100

92

96

96

ns

ns

ns

ns ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Open Surgical Treatment of Popliteal Artery Aneurysms