Chapter 41 Open Surgical and Endovascular Management of Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Open Surgical Management: Key Points

Key Technical Points for Open Repair of Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

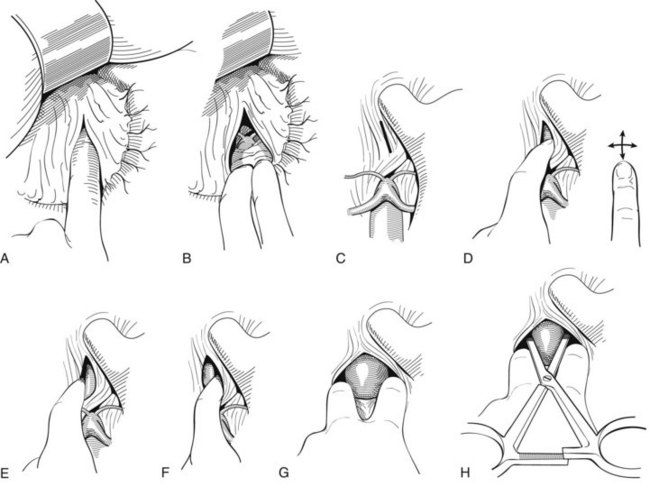

If the area of the infrarenal neck of the AAA is involved with hematoma, supraceliac aortic control should be obtained as shown in Figure 41-1; this is done without direct vision by tearing the lesser omentum with a finger (see Figure 41-1A). This process exposes the retroperitoneum above the celiac axis and pancreas (see Figure 41-1B). Next, using the gloved index finger and its nail, the posterior peritoneum over the diaphragmatic crura is torn as indicated by the line in Figure 41-1C, and the fingertip is pushed through the muscle fibers until the periadventitia of the aorta is encountered (see Figure 41-1D). Next, the finger bluntly dissects medially and laterally in the same plane, creating a potential space on both sides of the aorta (see Figure 41-1E to G). Two fingers are placed in the potential space and pulled caudally (see Figure 41-1G). A large curved DeBakey clamp is then placed vertically above the fingers into the space to occlude the aorta (see Figure 41-1H). The clamp will be occlusive only if the aorta is freed from the crural fibers anteriorly, medially, and laterally. It is also crucial to have a nasogastric tube in the esophagus during these maneuvers so that this structure can be identified and protected from injury.

FIGURE 41-1 Technique for occluding the supraceliac aorta without visualization of the structures dissected.

(Redrawn from Veith FJ, Gupta S, Daly V: Technique for occluding the supraceliac aorta through the abdomen. Surg Gynecol Obstet 151:648–650, 1980.)

Endovascular Management

History

Endovascular repair of a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (RAAA) was first performed successfully by Marin and colleagues in 1994.1 Another case was first reported by Yusuf and colleagues in 1994.2 Since then, many centers have used EVAR to treat RAAAs with varying results.3–12 Several groups have developed standardized systems of management in the RAAA setting, have used EVAR whenever possible, and have achieved good results.3–9 In contrast, other authors have used EVAR for RAAAs more selectively and have reported no better results with EVAR than with traditional open repair (OR).10–12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree