Figure 29.1 Computed tomography of the chest demonstrating a mass in the esophageal wall demonstrated by the arrow. The leiomyoma was located just above the azygos vein.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

More than 50% of leiomyomas are asymptomatic.3 Symptoms develop when the tumor has reached a large size, typically 5 cm or more.4 Dysphagia and retrosternal discomfort are the two most common symptoms. Respiratory complaints such as cough, dyspnea, or wheezing may result from large tumors causing compression of the tracheobronchial tree. Bleeding is uncommon since the overlying mucosa is almost always intact. Leiomyomas in the distal esophagus may be associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Diagnosis of leiomyoma can be made with confidence with a careful history, physical examination, barium swallow, computed tomography, and endoscopy with ultrasonography. Tissue diagnosis is not necessary except when the diagnosis of GIST or malignancy is a possibility. On endoscopic ultrasonography, typical leiomyomas appear as homogeneous anechoic lesions within the muscularis propria. A heterogeneous echo pattern may be seen in benign tumors but the presence of a lesion of greater than 4 cm is more suggestive of malignancy. Nonetheless, malignancy is exceedingly rare.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Leiomyomas grow slowly and may be stable in size during observation for many years. There is general consensus in the literature that esophageal leiomyomas should be surgically removed in symptomatic patients; however, treatment of asymptomatic patients continues to be debated. Many may advocate for the resection of these tumors because of the possibility of malignant degeneration, the possibility of symptom development in the future, the desire to obtain a definitive histologic diagnosis, and the ability to exclude the possibility of malignancy. However, the literature and experience have shown that asymptomatic patients rarely develop complications from their leiomyomas if untreated. Therefore, since the risk of malignant transformation is low and development of complications is rare in asymptomatic patients, it seems that asymptomatic patients with a tumor less than 2 to 3 cm can be managed with clinical and radiographic/endoscopic follow-up.3,4 Endoscopic ultrasound seems to be the ideal way to follow these tumors with a CT scan every 1 to 2 years. Indications for surgical resection of a leiomyoma include the following.

Symptoms – typically dysphagia and/or chest pain

Symptoms – typically dysphagia and/or chest pain

Increasing size of tumor during follow-up

Increasing size of tumor during follow-up

Need to obtain histologic diagnosis (i.e., clinical diagnosis is in doubt)

Need to obtain histologic diagnosis (i.e., clinical diagnosis is in doubt)

Facilitation of other esophageal procedures (i.e., fundoplication, myotomy)

Facilitation of other esophageal procedures (i.e., fundoplication, myotomy)

Giant leiomyomas requiring esophagectomy have been described but most commonly they can be treated effectively by esophageal-sparing techniques. Indications for esophagectomy include the following.

A very large or annular tumor that cannot be enucleated

A very large or annular tumor that cannot be enucleated

Esophageal mucosa or muscular wall that is badly ulcerated or damaged during enucleation that cannot be repaired in a satisfactory manner

Esophageal mucosa or muscular wall that is badly ulcerated or damaged during enucleation that cannot be repaired in a satisfactory manner

Symptomatic multiple leiomyomas that cannot be enucleated or diffuse leiomyomatosis

Symptomatic multiple leiomyomas that cannot be enucleated or diffuse leiomyomatosis

Leiomyosarcoma suspected and confirmed on biopsy

Leiomyosarcoma suspected and confirmed on biopsy

There are no specific contraindications for the resection of esophageal leiomyomas. Resection is typically contraindicated for small (1 to 2 cm) tumors in asymptomatic patients or when the general condition of the patient prohibits general anesthesia and complications of resection may outweigh the benefits.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Resection of esophageal leiomyomas can be performed by utilizing a number of approaches that include thoracotomy, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), and endoscopic resections when the lesion is small, pedunculated, and submucosal in location. Enucleation, or shelling out of the intramural leiomyoma, is the preferred treatment.3–7 Rarely, the tumor will require esophageal resection with reconstruction due to size and degree of esophageal involvement.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Anesthesia

For open thoracotomy, a thoracic epidural catheter is placed by the anesthesiologist for optimal management of postoperative pain. For thoracoscopic resection, an epidural is generally not necessary. The patient is intubated with a left double-lumen tube or a single-lumen tube and a bronchial blocker.

Positioning

Tumors of the upper and middle thoracic esophagus are best approached through a right lateral or posterolateral thoracotomy, while those in the lower third require a left thoracotomy (Fig. 29.2). Sequential compression devices are placed in the lower extremities to deter deep vein thrombosis. A Foley catheter is placed. The patient is then turned to the lateral position and a sandbag or a soft roll is placed under the upper ribs to avoid pressure on the brachial plexus, while the head is supported in neutral spine alignment. The arm on the side of the operation is supported and secured providing ample exposure of the axillary region. The lower leg is slightly bent at the knee while the upper leg is kept straight with pillows in between. Care is also taken to apply pads to all pressure points. The patient is supported on a bean bag which is set after the operating table is gently angulated at the level of the lower chest. A belt strap is placed over the hips to secure the patient to the table (Fig. 29.2). The chest is prepped and draped.

Figure 29.2 This picture demonstrates proper positioning of the patient for a left thoracotomy. Note the brake on the table, suspension of the left arm, and positioning of the legs. All pressure points are padded and the patient is secured to the table.

Technique

For leiomyoma, the principles of the operation include resection of the tumor (enucleation) without injury to the underlying mucosa or vagus nerves and closure of the muscularis propria, if possible, to prevent mucosal bulging and pseudodiverticulum formation.

On-table esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is performed to confirm tumor location and size and assure the surgeon that the lateral approach chosen (left or right) will work for the indicated patient.

On-table esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is performed to confirm tumor location and size and assure the surgeon that the lateral approach chosen (left or right) will work for the indicated patient.

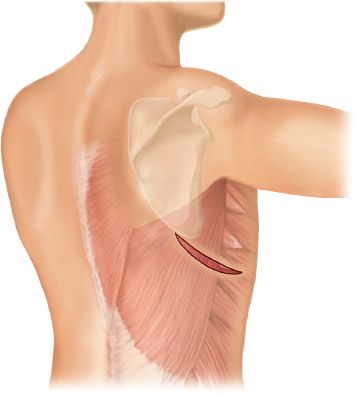

A standard lateral thoracotomy is performed (Fig. 29.3). On the right, the incision is planned to enter the chest at the level of the fifth intercostal space while on the left, at the level of the sixth or seventh intercostal space. Alternatively, a muscle-sparing thoracotomy can be performed, preserving the integrity of the latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles (Fig. 29.4).

A standard lateral thoracotomy is performed (Fig. 29.3). On the right, the incision is planned to enter the chest at the level of the fifth intercostal space while on the left, at the level of the sixth or seventh intercostal space. Alternatively, a muscle-sparing thoracotomy can be performed, preserving the integrity of the latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles (Fig. 29.4).

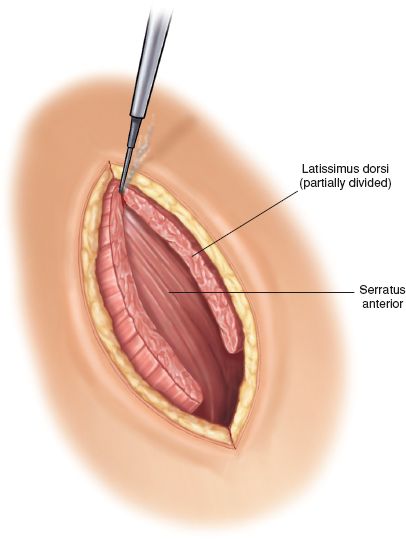

Once the subcutaneous tissues have been divided, the latissimus dorsi muscle is divided with cautery, while the serratus anterior muscle is mobilized anteriorly and preserved (Fig. 29.5).

Once the subcutaneous tissues have been divided, the latissimus dorsi muscle is divided with cautery, while the serratus anterior muscle is mobilized anteriorly and preserved (Fig. 29.5).

Figure 29.3 Skin incision for a lateral thoracotomy. The posterior margin of the incision ends at the angle of the ribs, preserving the trapezius and rhomboid major muscles, which are divided during a posterolateral thoracotomy.

Figure 29.4 Skin incision for a muscle-sparing thoracotomy. The incision extends from a point just posterior to the tip of the scapula to just anterior to the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi muscle. A plane of dissection is performed between the latissimus and serratus muscles and a retractor placed under both muscles. Undermined skin flaps facilitate mobilization and retraction of the muscles. Keeping the flaps small reduces the incidence of seroma formation.

Figure 29.5 The latissimus dorsi muscle is divided with electrocautery leaving the serratus anterior muscle intact.

Figure 29.6 The posterior border of the serratus anterior muscle is dissected and elevated. The muscle is retracted anteriorly and preserved intact.

The areolar tissue along the posterior edge of the serratus is divided obliquely extending inferiorly toward the anterior inferior margin of the latissimus (Fig. 29.6).

The areolar tissue along the posterior edge of the serratus is divided obliquely extending inferiorly toward the anterior inferior margin of the latissimus (Fig. 29.6).

A plane of dissection is established above the ribs, and a hand is inserted under the chest wall musculature to identify the first (flat upper surface) and second ribs (insertion of middle scalene muscle).

A plane of dissection is established above the ribs, and a hand is inserted under the chest wall musculature to identify the first (flat upper surface) and second ribs (insertion of middle scalene muscle).

The ribs are then counted, and the selected intercostal space for entry is identified. The intercostal tissues and pleura are divided along the top border of the corresponding rib and entry into the thoracic cavity is accomplished.

The ribs are then counted, and the selected intercostal space for entry is identified. The intercostal tissues and pleura are divided along the top border of the corresponding rib and entry into the thoracic cavity is accomplished.

The posterior margin of the thoracotomy is at the level of the longitudinal spinous ligament.

The posterior margin of the thoracotomy is at the level of the longitudinal spinous ligament.

The parietal pleura and intercostal muscles are incised from within the thoracic cavity beyond the external margin of the incision in an effort to further relax the opening. We do not routinely resect a portion of a rib.

The parietal pleura and intercostal muscles are incised from within the thoracic cavity beyond the external margin of the incision in an effort to further relax the opening. We do not routinely resect a portion of a rib.

A Rienhoff retractor is inserted and slowly opened. Gradual opening of the retractor to no more than 6 to 8 cm helps to prevent rib fractures and may reduce the occurrence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome. A Balfour retractor or a second Rienhoff retractor positioned anteroposteriorly in the soft tissues of the chest wall at a right angle to the Rienhoff retractor may help to improve exposure (Fig. 29.7).

A Rienhoff retractor is inserted and slowly opened. Gradual opening of the retractor to no more than 6 to 8 cm helps to prevent rib fractures and may reduce the occurrence of postthoracotomy pain syndrome. A Balfour retractor or a second Rienhoff retractor positioned anteroposteriorly in the soft tissues of the chest wall at a right angle to the Rienhoff retractor may help to improve exposure (Fig. 29.7).

The lung is mobilized anteriorly and the posterior mediastinum is exposed. A leiomyoma will often appear as a large bulge (>3 cm) under the parietal pleura covering the esophagus (Fig. 29.8).

The lung is mobilized anteriorly and the posterior mediastinum is exposed. A leiomyoma will often appear as a large bulge (>3 cm) under the parietal pleura covering the esophagus (Fig. 29.8).

Most leiomyomas are easily seen through the intact mediastinal pleura. If the leiomyoma is not immediately seen through the intact pleura, it will frequently become apparent after initial esophageal dissection. However, smaller, less than ideally situated leiomyoma may require simultaneous EGD and careful mobilization and palpation to confirm the location.

Most leiomyomas are easily seen through the intact mediastinal pleura. If the leiomyoma is not immediately seen through the intact pleura, it will frequently become apparent after initial esophageal dissection. However, smaller, less than ideally situated leiomyoma may require simultaneous EGD and careful mobilization and palpation to confirm the location.

The mediastinal pleura is incised to expose the leiomyoma and the esophagus above and below.

The mediastinal pleura is incised to expose the leiomyoma and the esophagus above and below.

Figure 29.7 Chest wall retractors are placed at right angles to separate the ribs and fully distract the soft tissues anteriorly and posteriorly. Care should be taken to limit the rib spreading to no more than 6 to 8 cm.