Open AAA Repair for Rupture

ANDREW LEAKE and RABIH A. CHAER

Presentation

A 68-year-old male presents to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of back pain. He describes a syncopal event 4 hours prior, with the onset of severe pain (8/10). The pain is in the midback area, is constant, and is not positional. He denies a history of trauma and any gastrointestinal complaints. His past medical history is significant for coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. His father had an aneurysm, but does not recall the details. He denies a history of prior back pain and has not previously been evaluated for an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). His current medications are metoprolol, simvastatin, and aspirin. He currently smokes 1 pack per day of cigarettes, with a 60-pack-year history. In the ED, his vital signs are as follows: temperature, 37.9°C; blood pressure, 110/62 mm Hg; heart rate, 110 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 19 per minute; and saturations, 98% on 2 L nasal cannulas. He appears uncomfortable but is mentating appropriately. Abdominal examination reveals midabdominal tenderness with guarding, but no peritoneal signs. Deep palpation in the periumbilical area identifies a pulsatile mass. No abdominal or inguinal hernias are appreciated. Femoral, popliteal, and pedal pulses are normal in both extremities.

Differential Diagnosis

The initial presentation of a patient with a ruptured AAA is variable, and the differential diagnosis is broad (Table 1). The most common chief complaints are abdominal, back, or groin pain. Identified factors that predispose a patient to the development of an AAA include male gender, increasing age, family history, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and smoking. Smoking is the strongest risk factor for AAA development. This patient presents with multiple risk factors, and a high clinical suspicion is necessary for early recognition.

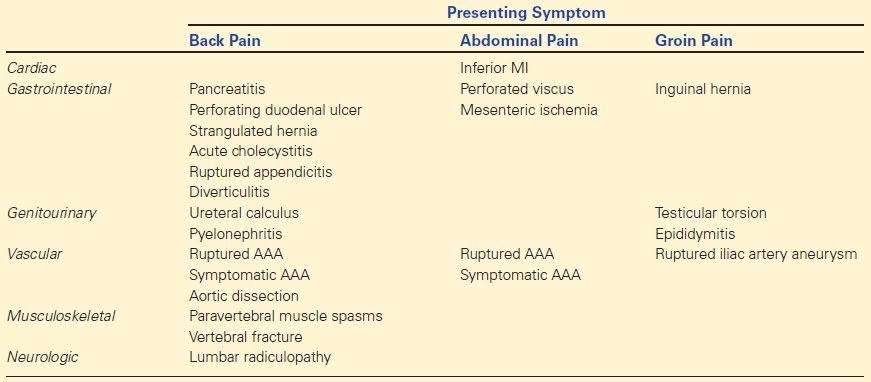

TABLE 1. Differential Diagnosis for Back, Abdominal, and Groin Pain in Patients Presenting to an Emergency Room

AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Workup

The clinical triad of sudden onset of abdominal (or back) pain, hypotension, and pulsatile abdominal mass is characteristic of a ruptured AAA. It is present in less than 50% of the patients with ruptured AAAs. With this constellation of symptoms, ruptured AAA must be considered among the most likely diagnoses and must be ruled out.

Management options at this point are dictated by the hemodynamic stability of the patient. The unstable patient with a high clinical suspicion for a ruptured AAA should be transported emergently to the operating room for surgical intervention. At medical facilities unable to offer urgent surgical repair, rapid stabilization and transport to an appropriate institution should be expedited. Resuscitation until definitive repair should allow permissive hypotension. Aggressive resuscitation with crystalloid should be avoided, as it has been shown to increase bleeding and worsen coagulopathy. Resuscitation goals are aimed at maintaining cerebral and myocardial perfusion by monitoring consciousness and ST changes on cardiac monitoring (systolic blood pressure 70 to 80 mm Hg).

In a patient with stable vital signs, computed tomography (CT) imaging is critical for accurate diagnosis. Prior to any transportation, large-bore peripheral IVs should be placed and a blood sample sent for cross-matching. The abdominal/pelvic CT scan should be obtained using a 3-mm (thin)-cut protocol with intravenous contrast, to assess for possible endovascular repair (EVAR). Oral contrast is not indicated, as it may degrade the image quality of vascular structures due to artifact and carries the risk of delaying intervention. Continuous monitoring and supervision by the surgical team is essential prior to definitive repair.

Case Continued

The patient is alert and remains hemodynamically stable, and a CTA is immediately obtained.

Diagnosis and Treatment

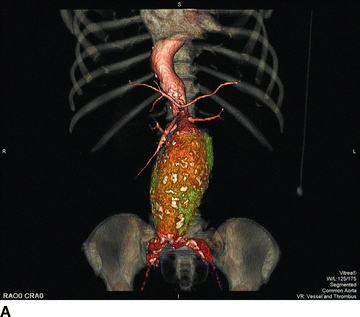

The CT scan shows a ruptured AAA, requiring immediate repair (Fig. 1). Current repair options for ruptured AAA include either an open standard repair (OSR) or an EVAR. Widely accepted exclusion criteria for EVAR include proximal neck length less than 10 mm, proximal neck diameter greater than 32 mm, neck angulation greater than 60 degrees, and external iliac diameter of less than 6 mm. This patient is excluded from EVAR because of short proximal neck length and will require an OSR.

FIGURE 1 CT scan. CT scan shows an AAA from the renal arteries to the aortic bifurcation (A), with a maximum diameter of 8.4 cm (B). There is a large right-sided retroperitoneal hematoma (arrows). Detailed examination of the infrarenal aorta demonstrates a proximal neck diameter of 32 mm, a proximal neck length of 5 mm, with 30-degree angulation. Common iliac arteries are 15 mm bilaterally (from personal patient file).

Surgical Approach

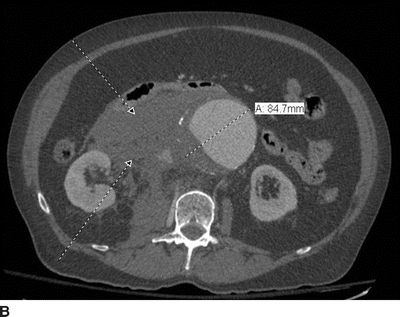

Prior to the initial arrival of the patient with a suspected ruptured AAA, the operating room staff is contacted to begin preparations including cross-matching of blood products and assembly of a cell-scavenging system. Before induction of general anesthesia, prophylactic antibiotics are administered and the patient is prepped and draped from his nipples to his knees. Immediately upon induction, the operation is initiated through either a transperitoneal or retroperitoneal incision. Our preference is a transperitoneal incision through a vertical midline abdominal incision, extending from the xiphoid process to just below the umbilicus. Proximal aortic control is the first critical step. In the unstable patient, supraceliac control and clamping can be done quickly (Fig. 2). A nasogastric tube can be placed to avoid esophageal injury while resecting the left crus of the diaphragm. If the patient remains stable, the aortic clamp is not applied; however, it may be left in position in case the patient decompensates during dissection of the aneurysm. Supraceliac aortic clamping is associated with increased ischemic injury to liver, bowel, and kidneys and should be moved to an infrarenal location when appropriate. Alternative proximal control measures include an aortic compressor, which is used to compress the aorta against the spine, or an intra-arterial occlusion balloon. Once proximal control is achieved, the anesthesia team may maximize their resuscitation efforts in anticipation of subsequent blood loss.

FIGURE 2 Supraceliac control, exposure of the supraceliac aorta. A: Lesser sac is entered by incising the gastrohepatic ligaments (dotted line). B: The diaphragmatic crura is now visualized. C: The crus is either sharply or bluntly opened to gain access to the supraceliac aorta. D: After blunt dissection on both sides of aorta to the spine is accomplished, the clamp is placed. (From Mulholland MW, ed. Operative Techniques in Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015.)