On-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

Peter K. Smith

Jacob N. Schroder

Indications

The goals of surgical revascularization can be divided into two categories: improved survival and symptom relief. The indications for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) are summarized in the current American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines and are based upon anatomic and physiologic factors. The most common indications include:

Significant (>50%) left main stenosis

Significant (>70%) stenosis in three major coronary arteries (especially in patients with diabetes mellitus), or two-vessel CAD including the proximal LAD

Significant (>70%) stenosis in two major coronary arteries with extensive myocardial ischemia

Significant (>70%) multivessel disease and mild to moderate LV systolic dysfunction

Significant (>70%) proximal LAD stenosis and extensive ischemia

Survivors of sudden cardiac death with presumed ischemia-mediated ventricular tachycardia caused by significant (>70) stenosis in a major coronary artery

Patients with one or more significant (>70%) coronary artery stenoses and unacceptable angina despite optimal medical therapies

Failed percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or anatomy not suitable for PCI

Mechanical complications of myocardial infarction (MI) (ventricular septal defect, papillary muscle rupture, myocardial rupture)

Contraindications

The contraindications for CABG are based on both technical and patient factors, but are directed by the feasibility of providing as complete revascularization as possible and

providing symptom control and a survival benefit. Anatomic considerations such as target arteries that are too small or diffusely diseased may contraindicate CABG. Patient comorbidities such as severe COPD, extreme obesity, extensive cerebrovascular disease or significant frailty, can significantly increase the risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality and warrant careful evaluation and consideration. Any coexisting condition that significantly limits life expectancy (such as malignancy, significant liver disease with synthetic dysfunction) should be a contraindication to surgical revascularization. Although increasing age confers an increasing risk of mortality, advanced age is not in itself a contraindication.

providing symptom control and a survival benefit. Anatomic considerations such as target arteries that are too small or diffusely diseased may contraindicate CABG. Patient comorbidities such as severe COPD, extreme obesity, extensive cerebrovascular disease or significant frailty, can significantly increase the risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality and warrant careful evaluation and consideration. Any coexisting condition that significantly limits life expectancy (such as malignancy, significant liver disease with synthetic dysfunction) should be a contraindication to surgical revascularization. Although increasing age confers an increasing risk of mortality, advanced age is not in itself a contraindication.

The most appropriate revascularization strategy (CABG vs. percutaneous intervention) should be determined by close collaboration between the cardiology and cardiac surgery teams, with adherence to current revascularization guidelines and appropriate use criteria (the “Heart Team” approach).

A thorough history and physical examination and careful evaluation of all preoperative studies should be completed to determine the appropriateness of the therapy and minimize complications. This is particularly true for coronary bypass patients, who frequently are evaluated by multiple, highly focused expert subspecialists to whom the comorbidities and complex multiple medical problems are relatively unimportant for their diagnostic work.

Careful examination of the neurologic, cardiac, pulmonary, and peripheral vascular systems may elicit signs or symptoms, which warrant further investigation (such as history of TIAs and performing carotid duplex, a history of COPD and performing pulmonary function tests or the presence of a cardiac murmur and performing transthoracic echocardiography).

In addition to overall risk assessment there are additional CABG-specific considerations when performing the preoperative history and physical examination:

The blood pressure should be monitored in both upper extremities. A discrepancy of greater than 10 mm Hg could suggest subclavian artery stenosis and would warrant investigation to ensure adequate internal mammary artery (IMA) flow.

A history of prior blunt or penetrating chest trauma may also indicate the possibility of occult cardiac injury or damage to the IMA.

The presence of significant peripheral vascular disease is associated with aortic atherosclerotic disease and should raise the index of suspicion for ascending aortic disease and the need for alternate techniques to minimize embolic complications.

Careful examination, and possibly vein mapping, of the lower extremities is necessary to determine the suitability of the greater saphenous veins for use as conduits.

An Allen test should be performed in the nondominant arm of all patients in whom the radial artery may be used as a conduit.

Patients should receive prophylactic antibiotics 30 to 60 minutes prior to incision. It is our preference to use cefoxitin in patients who are not beta-lactam allergic and to add vancomycin if the patient has high risk features, such as MRSA colonization or being hospitalized more than 24 hours prior to the operation. All patients should have central venous access, an arterial line, and some means to measure core temperature, such as a temperature sensing Foley catheter. A pulmonary artery catheter should be used for patients with reduced left ventricular function or known pulmonary arterial hypertension. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is now standard for all cardiac surgery operations, and a complete examination is mandatory prior to skin incision.

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position with the arms adequately padded and tucked to the sides. If the radial artery is to be used, the nondominant arm is positioned out to the side with a sterile pulse oximetry probe. The patient is then prepped from chin to toes, with a circumferential prep of the legs. It is our policy to first scrub the patient with a chlorhexidine agent, followed by an adherent, alcohol-based iodine or chlorhexidine skin prep. A time out to ensure that the prep is dry and that there has been no “pooling” is imperative as a fire safety measure.

Technique

Conduit Harvesting

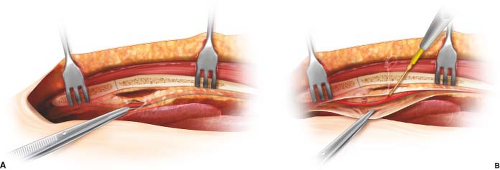

A standard median sternotomy is performed and IMAs are harvested in either a skeletonized or pedicled fashion. The pedicled IMA dissection involves harvesting the IMA with the medial and lateral internal mammary veins along with the internal thoracic fascia. A skeletonized dissection involves harvesting the IMA alone. Skeletonization theoretically leaves the chest wall arterial collaterals, internal mammary veins, and lymphatics intact. It is speculated that this may improve sternal healing and reduce the incidence of infection (Fig. 25.1). This also adds significant length to the IMA conduit.

Simultaneously, the greater saphenous and/or the radial artery is harvested by either open or endoscopic techniques. There have been suggestions that endoscopic vein harvesting may reduce conduit performance, however, these data are conflicting. This topic is currently being evaluated in a randomized trial, but our practice continues to use endoscopic harvesting almost exclusively. A small dose of intravenous heparin (2,500 to 5,000 units) is given during conduit harvest to prevent thrombus formation, especially in the saphenous vein. Prior to transecting the distal end of the IMA, the patient is fully anticoagulated with heparin (goal activated clotting time >480 seconds). The distal IMA is transected and a topical solution, such as papaverine, is applied to reverse any arterial spasm caused by the harvesting process.

Cannulation for Cardiopulmonary Bypass

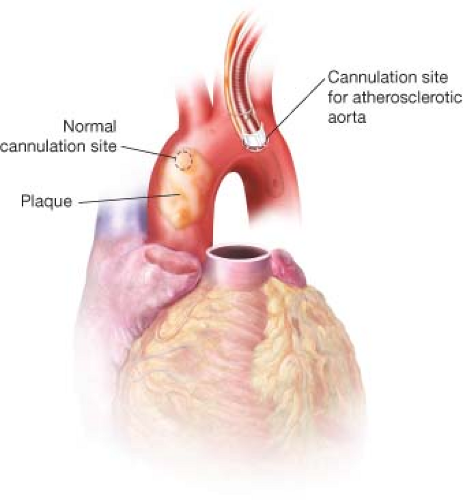

The pericardium is incised anteriorly (and laterally on the diaphragmatic surface) exposing the heart. The pericardial well is created by securing the pericardial edges to the retractor or skin with sutures. Digital palpation is notoriously inaccurate in detecting atherosclerotic disease. It is our preference that epiaortic echo be completed on all patients to better detect atherosclerotic plaque and thus minimize embolic phenomenon. If disease is detected, alternate sites for cannulation (proximal arch, right axillary or femoral artery) may be chosen (Fig. 25.2).

If the disease is diffuse and the cross-clamp cannot be applied safely, the procedure can be performed either off-pump or on-pump beating heart, minimizing aortic manipulation.

Two concentric purse-string sutures are placed in the aorta at the site of cannulation. Care must be taken to place these sutures into the media of the aorta to avoid hematoma formation. The aorta is incised and the appropriately sized cannula is inserted and secured. The cannula is de-aired and connected to arterial inflow line. Typically, a purse-string suture is placed in the right atrium and a dual- or triple-staged venous cannula is placed with the tip extending into the IVC. Independent cannulation of the SVC and IVC is sometimes used to improve venous drainage and prevent RV injury due to exposure to systemic temperatures during cardioplegic arrest. This may also be necessary to provide adequate drainage if the heart is to be displaced into the right chest to expose the proximal circumflex marginal or the circumflex proper. Once this is completed CPB is initiated. CPB initiation is a critical event requiring the full attention of the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and perfusionist. It is essential that arterial inflow is proven to be unobstructed before venous drainage is freely allowed, which otherwise could result in exsanguination. Issues with arterial inflow due to cannula malposition, aortic dissection, or even an overlooked tubing clamp must be assessed and corrected. Once CPB is safely established, ventilation is stopped and the patient cooled (our preference is cooling to 32° to 34°C for most CABG patients). If a PA catheter has been placed, it must be withdrawn into the main PA before the ventilator is discontinued, to avoid the frequently fatal complication of PA catheter pulmonary vascular injury. This injury risk is increased with more profound hypothermia that stiffens the catheter.

Inadequate venous drainage must be corrected to avoid hypoxia through continued ejection of both right and left ventricles, with systemic oxygen desaturation by admixture of blood traversing the unventilated lungs. Additionally, elevated central venous pressure associated with poor venous drainage decreases the transcerebral pressure gradient. Inadequate venous return is often associated with the reduced arterial inflow (and arterial pressure) which can further reduce the pressure gradient placing the patient at risk for cerebral hypoperfusion and injury.

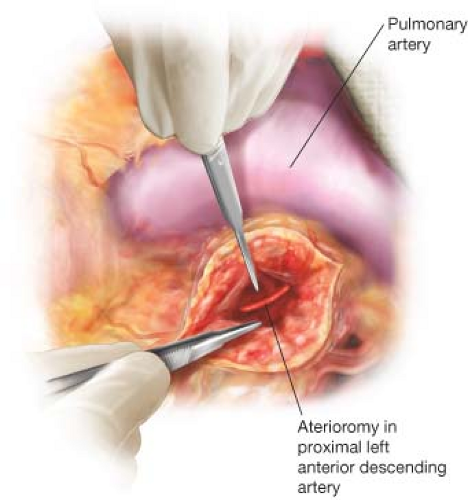

Evaluation of Coronary Targets

Once full cardiopulmonary bypass is achieved and the heart is decompressed, the coronary targets are evaluated. Most of the targets for revascularization can be easily identified

by visual inspection and gentle palpation to ensure that there is minimal or no atherosclerotic disease at each proposed site. These sites and the visible coronary anatomy are compared to the angiogram, which must be available in the operating room.

by visual inspection and gentle palpation to ensure that there is minimal or no atherosclerotic disease at each proposed site. These sites and the visible coronary anatomy are compared to the angiogram, which must be available in the operating room.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree