Foreign bodies in the airway of a 14-month-old patient with a history of penetration syndrome. Chest x-rays obtained on inspiration (a) and expiration (b) show greater transparency in the right lung. On expiration, air trapping in the right lung is evident and is due to the valve mechanism, which determines a mass effect of that lung and displacement of the heart and mediastinum to the left. The air-trapping area excludes the right upper lobe, which is displaced cephalad (arrow). This is indicative of the presence of a foreign body in the right intermediate bronchus, which was confirmed by fiberoptic bronchoscopy. The foreign body (a peanut) was later extracted

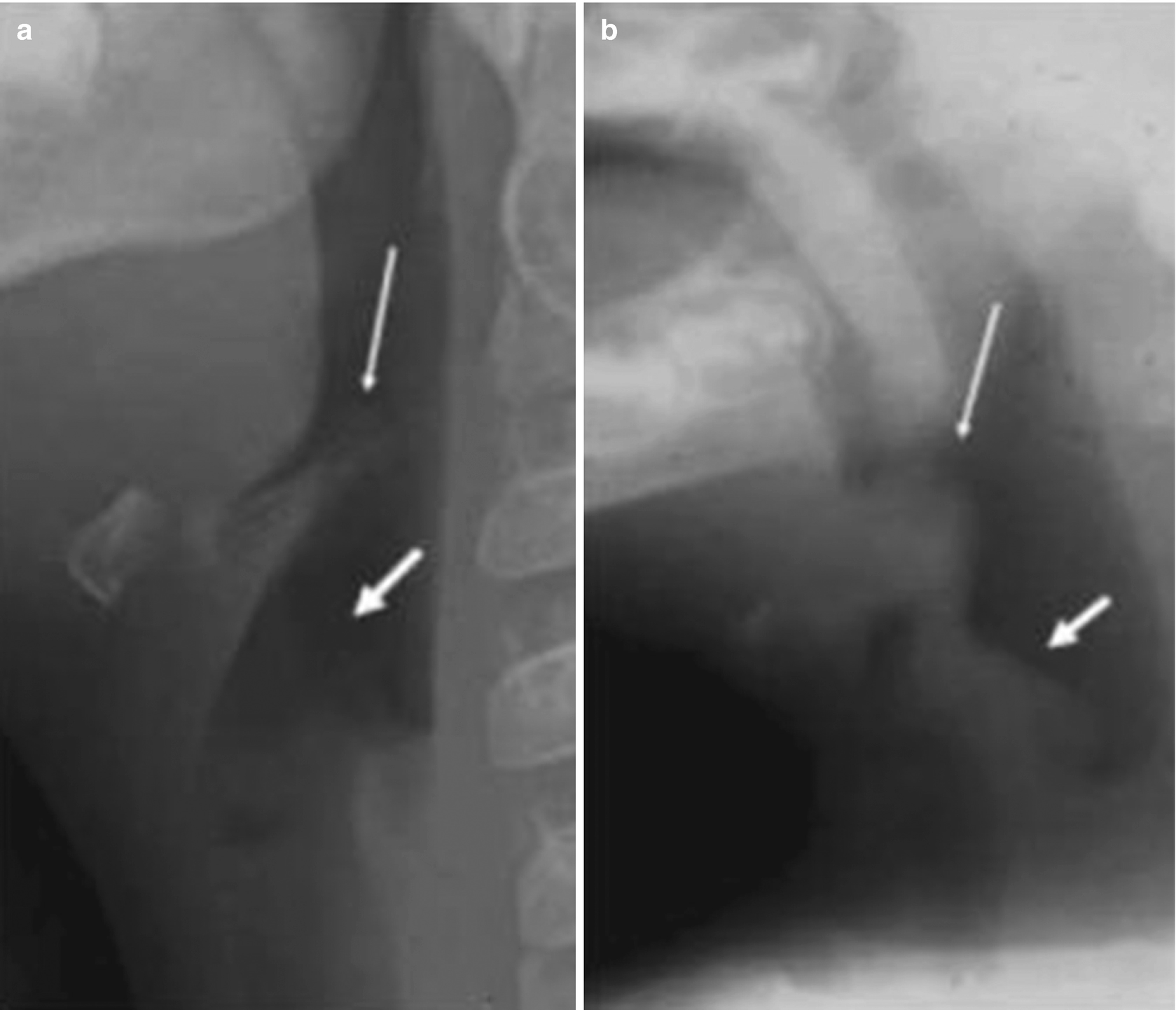

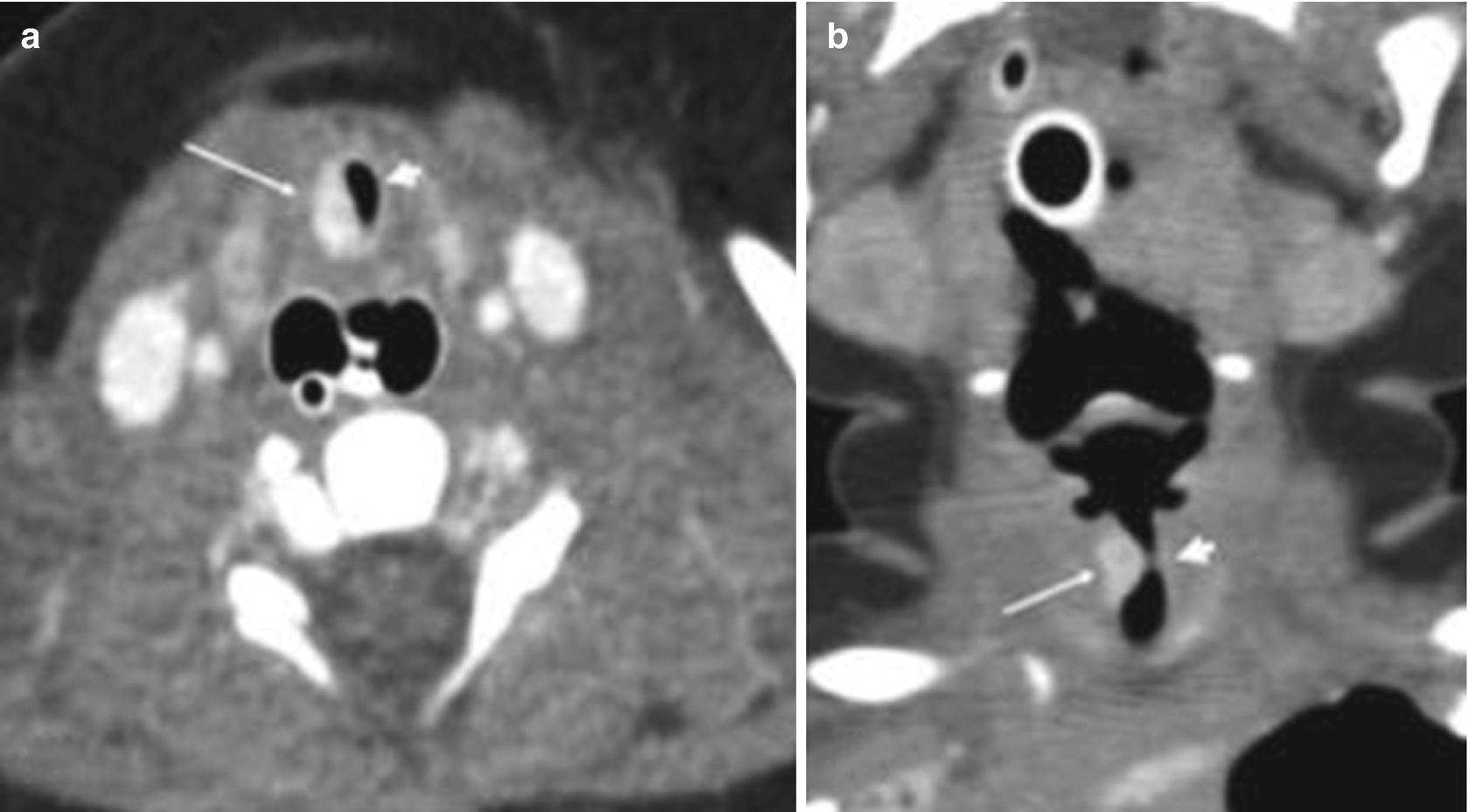

Acute epiglottitis. (a) Lateral neck x-ray of a 3-year-old patient, showing the epiglottis (thin arrow) and the aryepiglottic folds (thick arrow), both of normal size and thickness. (b) X-ray of a 2-year-old patient with an acute stridor, showing significant thickening of the epiglottis (thin arrow) and of the aryepiglottic folds (thick arrow)

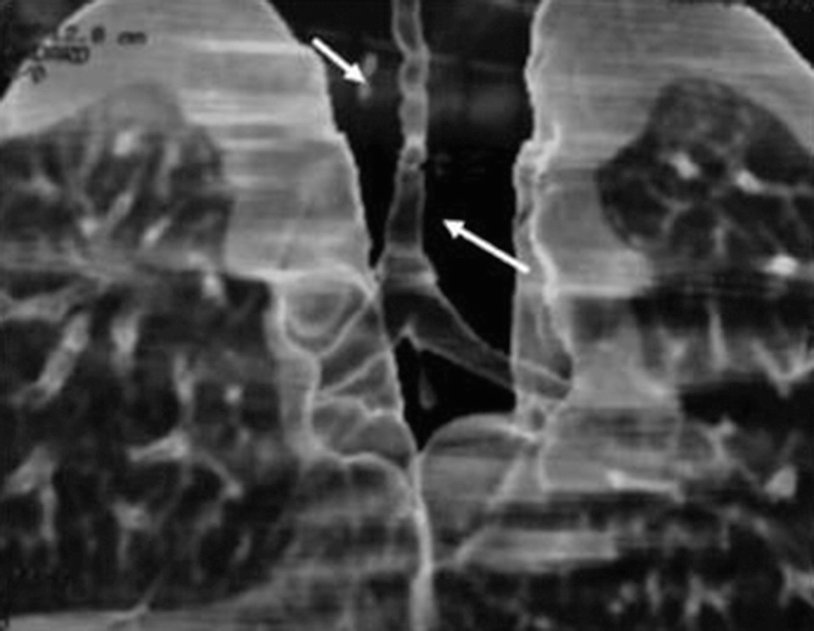

Congenital tracheal stenosis in a 2-month-old patient with a congenital stridor. A multislice CT scan with three-dimensional reconstruction of the airway shows a long segment of tracheal stenosis (arrows)

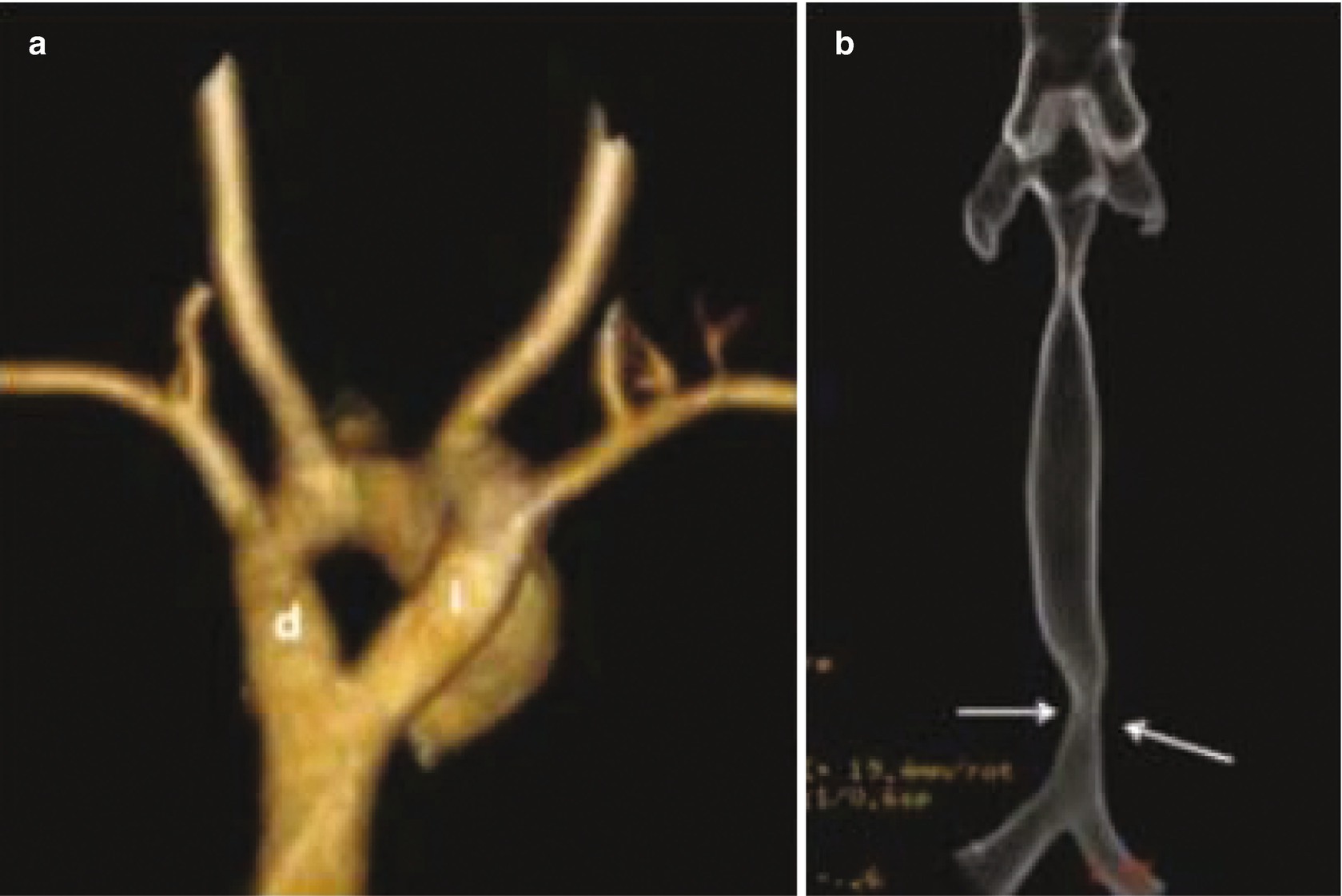

Vascular ring in a 4-month-old patient with a congenital stridor, shown on multidetector helical CT scans with three-dimensional reconstruction. (a) An anteroposterior view shows a double aortic arch (d: right arch; i: left arch). (b) An anteroposterior view of the trachea shows compression and narrowing of its distal end, due to the vascular ring (arrows)

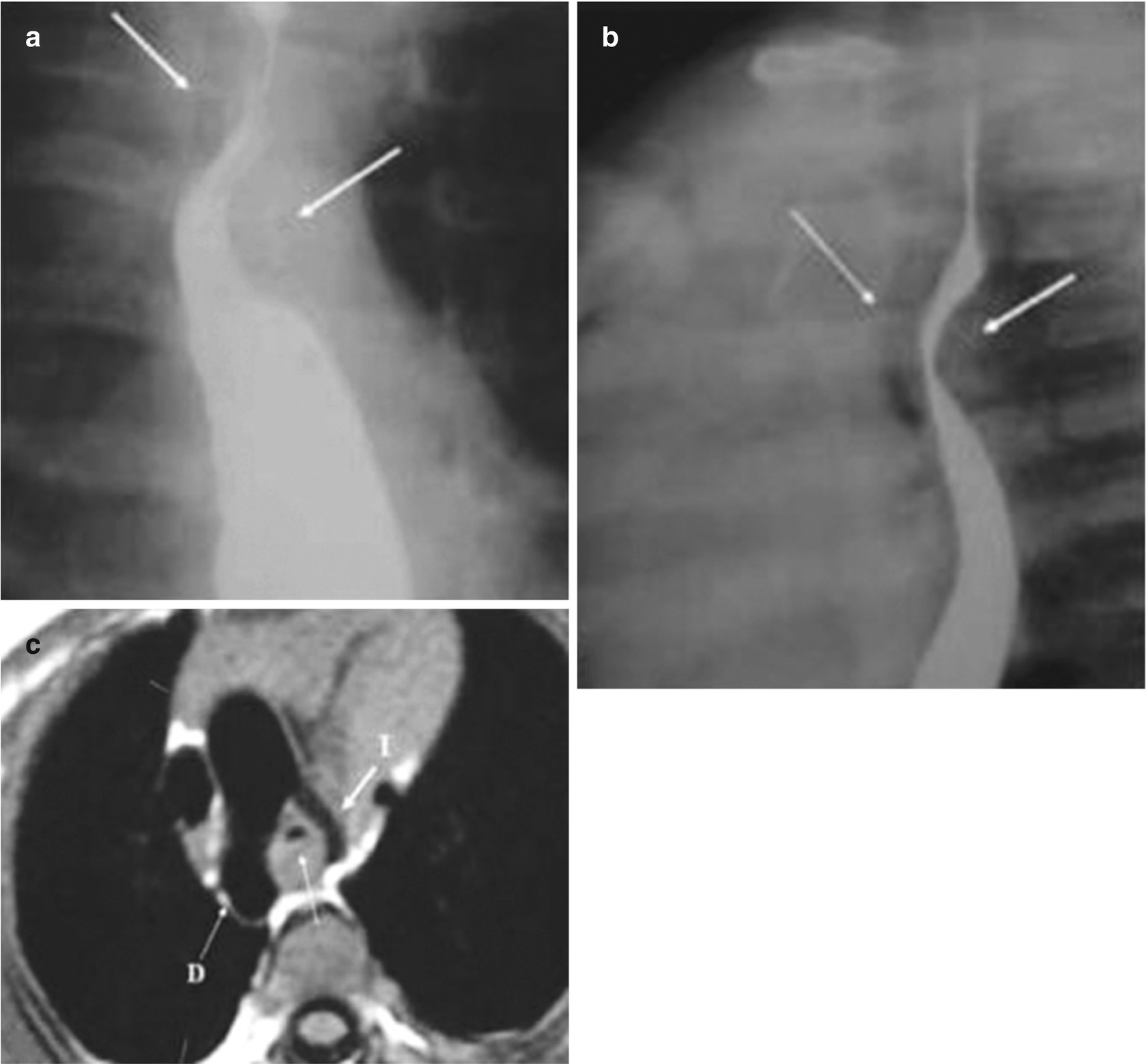

Vascular ring and double aortic arch in a 3-month-old patient with a congenital stridor. An esophagram in the anteroposterior view (a) shows posterior compression of the esophagus (arrows); the lateral view (b) shows posterior compression of the esophagus (posterior arrow) and compression of the airway (thin anterior arrow). An axial T2-weighted MRI of the chest (c) shows the right aortic arch (D) and left aortic arch (I) with airway compression

Subglottic hemangioma in a 5-day-old newborn with a progressive stridor. Multidetector helical CT scans obtained after intravenous contrast administration show, in the axial section (a) and coronal reconstruction (b) of the neck, severe stenosis of the subglottic airway (arrowhead) secondary to a lesion intensely impregnated with contrast, compatible with a hemangioma (thin arrows)

The Lung Parenchyma

Congenital Anomalies

Congenital bronchopulmonary anomalies are common and are composed of a heterogeneous group of anomalies that affect the pulmonary parenchyma, its vascularization, and the lower airway. More than one anomaly can coexist (hybrid forms), and their clinical presentation is variable. They have been classified in different ways by different authors—in particular, according to their anatomy and pathogeny.

A simple classification considers two types: (1) focal malformations (congenital pulmonary hyperinsufflation, bronchial atresia, simple intrapulmonary cysts, congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM), pulmonary sequestration, and an irrigation system congenitally isolated from a normal lung segment); and (2) a dysmorphic lung (pulmonary aplasia–hypoplasia complex, lobar agenesis–hypoplasia).

Imaging studies are fundamental for diagnosis, and several methods can be used.

Congenital Pulmonary Hyperinflation

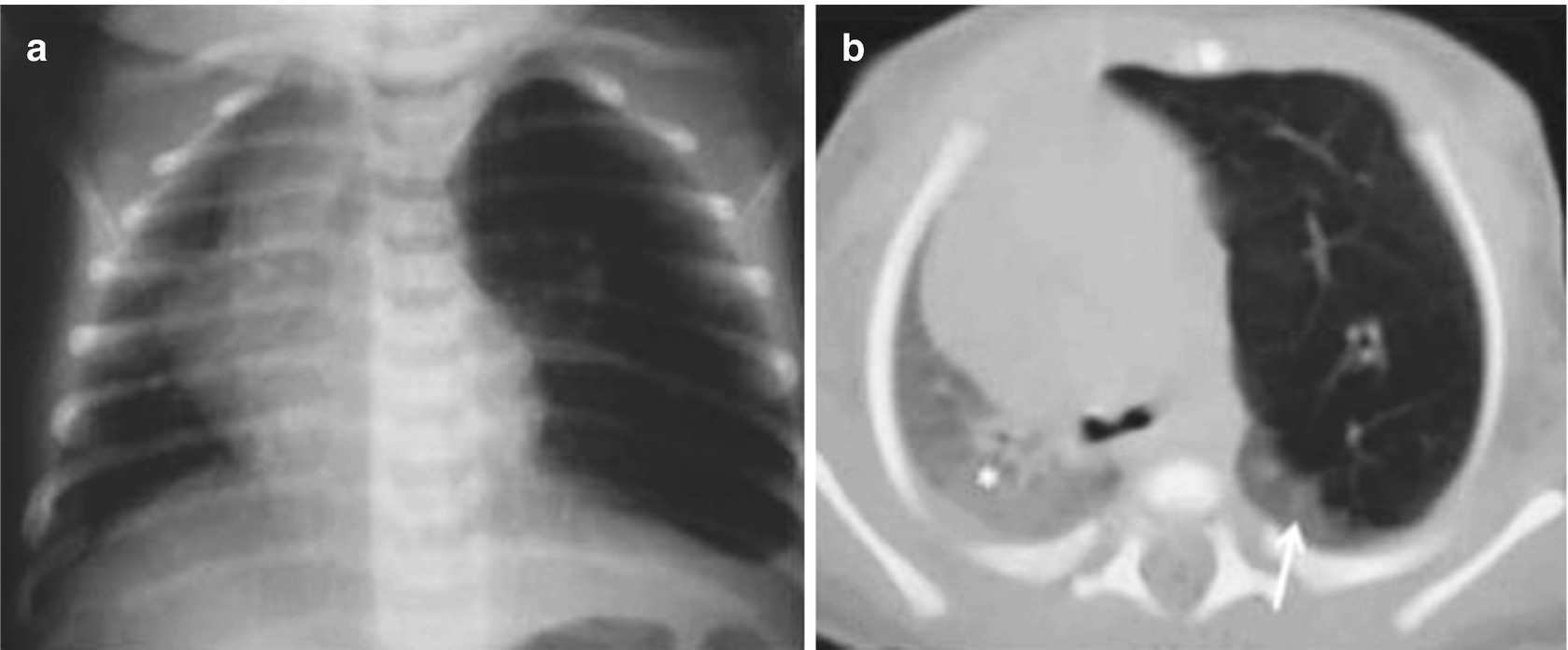

Congenital lobar overinflation in a 3-day-old newborn with progressive difficulty breathing. (a) A chest x-ray shows hyperinflation of the left upper lobe with secondary displacement of the heart and mediastinum to the right. (b) A CT scan of the chest shows localized hyperinflation of the left upper lobe with displacement of the mediastinal structures and compression of the left lower lobe (arrow) and right lung (asterisk)

Bronchial Atresia

Bronchial atresia in a 12-year-old girl with a history of recent right pneumonia. A CT scan of the chest below the carina shows a zone of greater transparency in the right lung (thin arrows), associated with mucosal impaction and a mucocele in the hilar region on the same side (thick arrow). There are also two thin-walled cystic masses inside, compatible with a congenital pulmonary airway malformation (formerly known as a congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation) (curved arrows)

Isolated or Single Congenital Chest Cysts

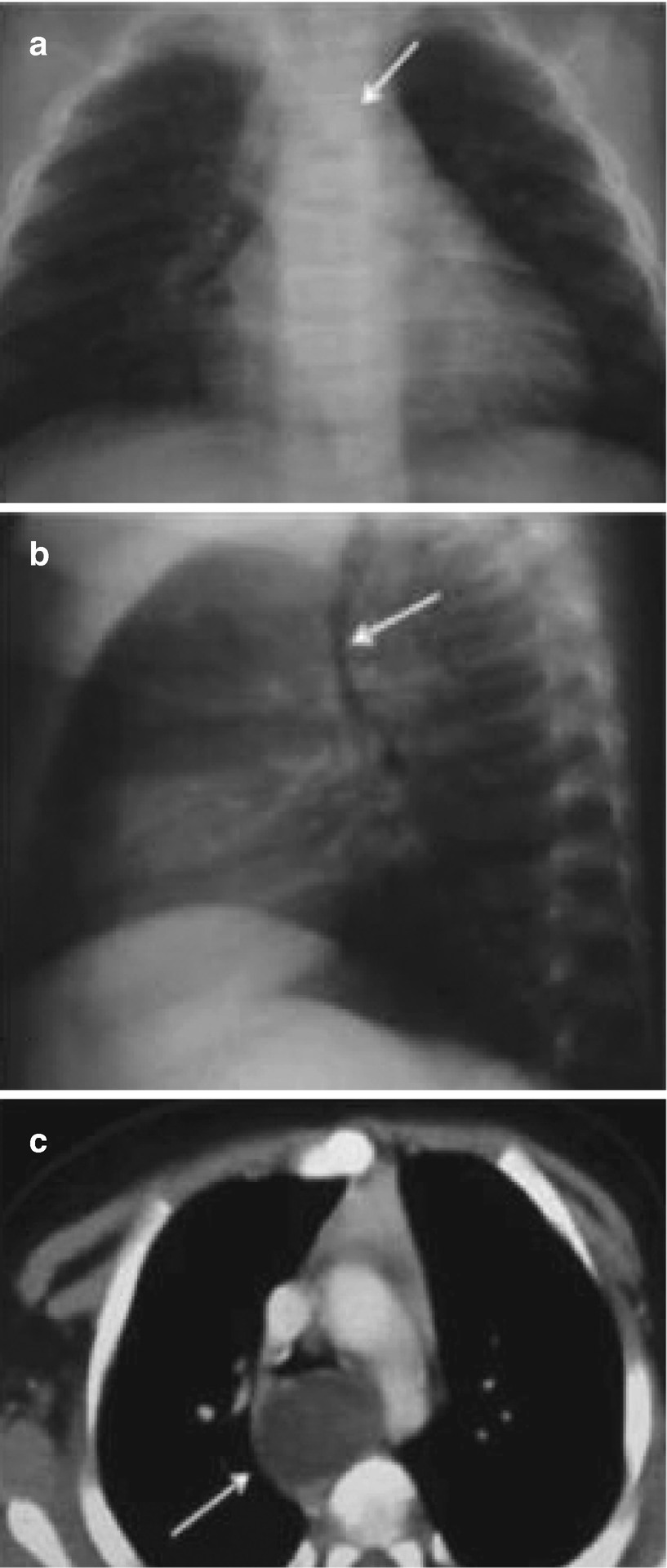

Bronchogenic cysts in a 2-month-old infant with bronchial obstruction syndrome. Chest x-rays in the anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) views show a mass in the posterior mediastinum that displaces the trachea to the right and anteriorly (arrows). (c) An axial CT scan with intravenous enhancement at the carina level confirms a cystic mass that compresses and displaces the trachea anteriorly (arrow)

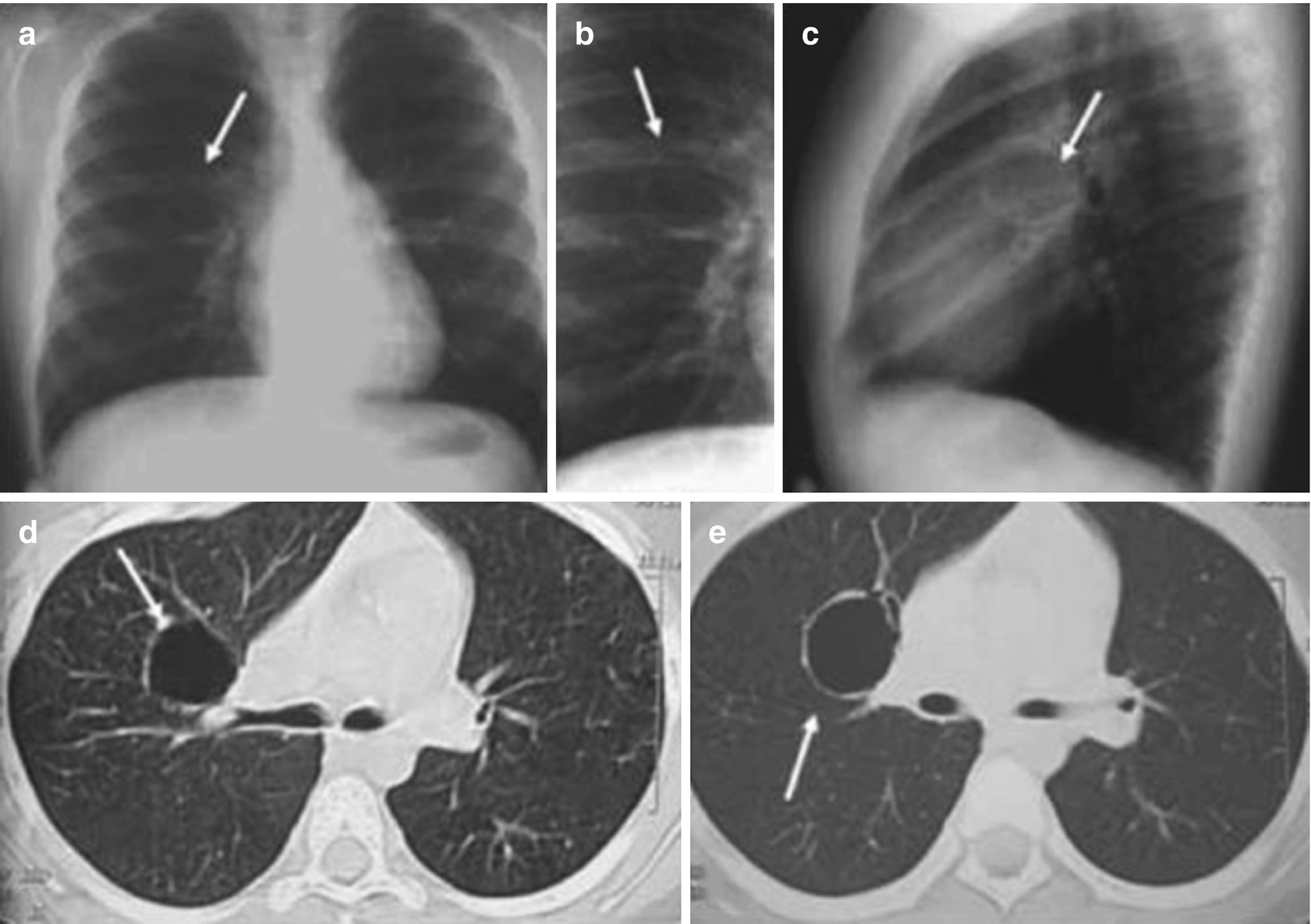

Bronchogenic cysts in an 11-year-old boy with radiographic findings. Chest x-rays in the anteroposterior (a), AP localized (b), and lateral (c) views show a rounded radiolucent image of thin walls with air in the interior of the right upper lobe (arrows). Axial CT scanning of the chest (d, e) below the carina confirms a thin-walled cystic lesion (arrows)

Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

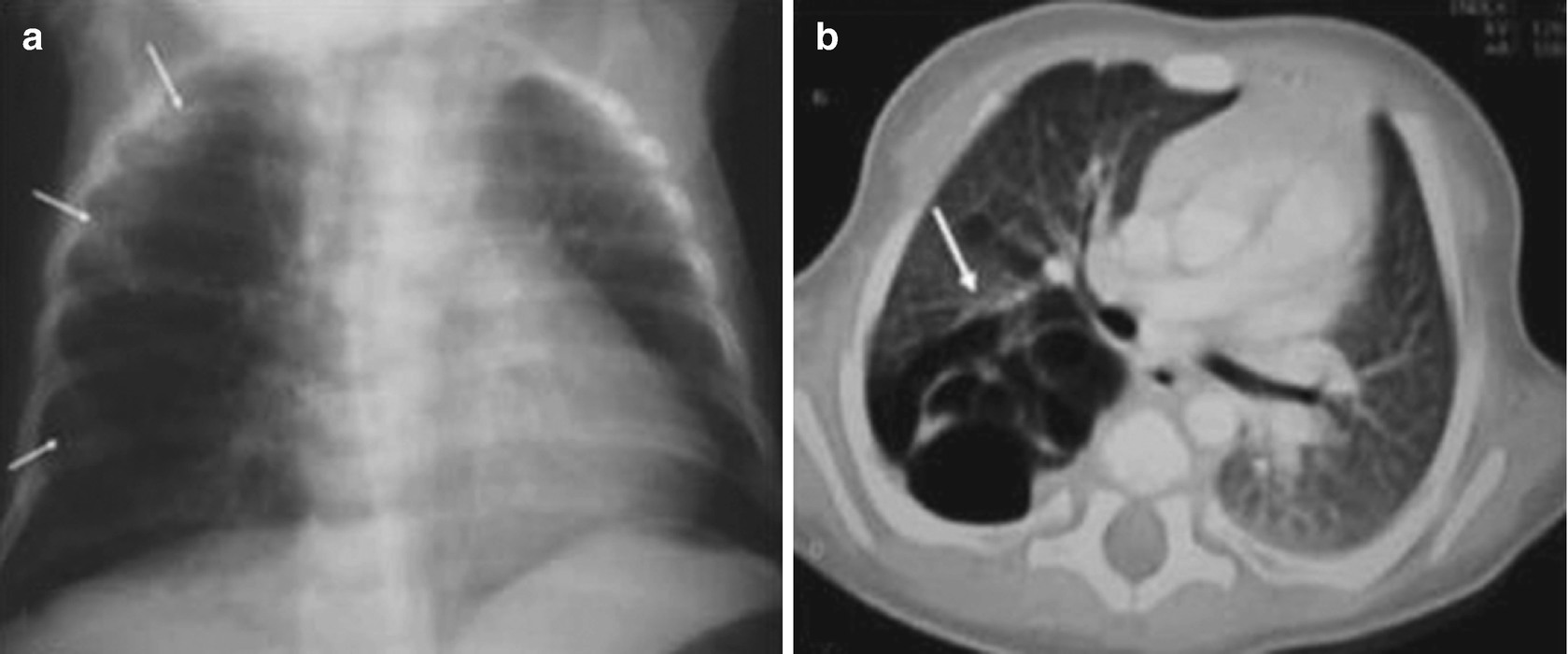

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation in a 2-month-old infant with a cough and breathing difficulty. (a) A chest x-ray shows a transparent cystic mass, with thin walls, in the right lung (arrows). (b) A CT scan of the chest shows that this mass is multicystic in appearance, is in the posterior aspect of the lung on that side (with upper and lower lobe involvement (arrows)), and causes a mass effect, with mediastinal displacement toward the left

The clinical picture varies according to the patient’s age, the size of the lesion, and whether there are associated anomalies or complications. Patients may present respiratory distress during the neonatal period or remain asymptomatic for variable periods of time. This condition may also appear as recurrent pneumonia; sometimes it appears as an incidental finding or may be detected in routine prenatal ultrasound examinations.

Types I and II can grow progressively with time, communicate with the airway, and fill with air. According to the type of CPAM, a chest x-ray shows areas of greater or lesser lung transparency, with a mass effect on other chest structures, which can be confused with congenital pulmonary hyperinflation or a diaphragmatic hernia.

Chest CT is fundamental in diagnosis because it not only enables characterization of lesions and shows their location and extension, but also allows them to be differentiated from other diseases. Differential diagnosis for CPAM should include pleuropulmonary blastoma, particularly for type IV.

Pulmonary Sequestration

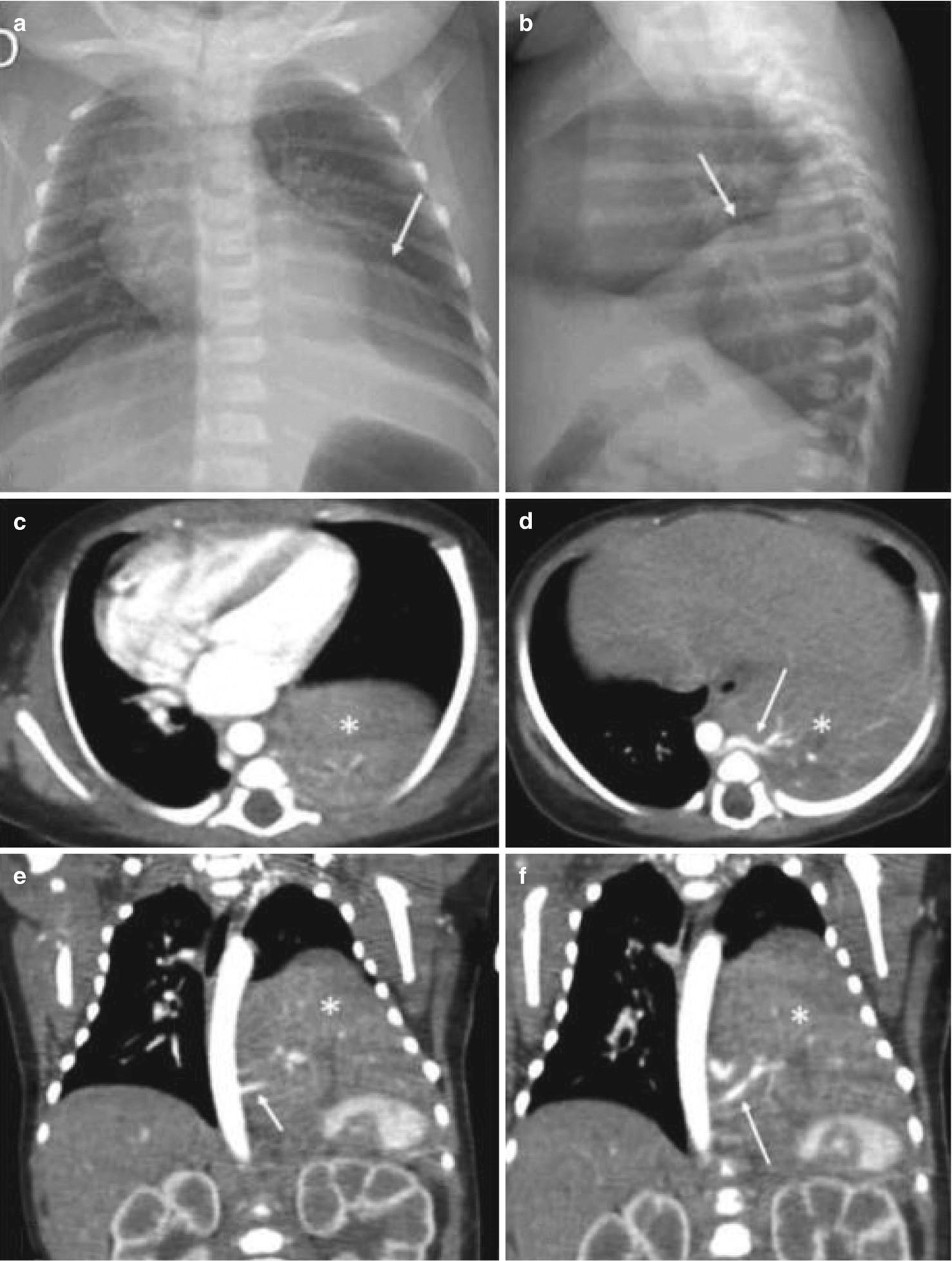

Pulmonary sequestration is a congenital anomaly characterized by an aberrant pulmonary tissue mass that does not have a normal connection with the tracheobronchial tree or pulmonary arteries. It is usually irrigated by an arterial anomaly that originates directly from the aorta with venous drainage through the azygos system, pulmonary veins, or inferior vena cava. It normally appears as pneumonia, although (depending on its size) it can also appear as a chest mass that causes respiratory distress in newborns.

Pulmonary sequestration is most often found in the basal segments of the lower lobes, particularly in the medial zone of the lower left lobe. It has traditionally been divided into two types: intralobar and extralobar. In the former, sequestration is contained within the adjacent lobe, with which it shares its pleural covering and venous drainage, normally through the pulmonary veins. Extralobar sequestration is most often located between the lower lobe and the diaphragm, and has its own pleural covering. Around 90% of cases are located on the left side, and the venous drainage is commonly via the azygos system.

The clinical picture is diverse. Most cases of intralobar sequestration involve a history of recurrent focal pneumonia, but some of them appear as an incidental finding, particularly in newborns and infants. Extralobar sequestration is most often diagnosed during the first 6 months of life with clinical manifestations such as dyspnea, cyanosis, and difficulty feeding. It can be associated with other anomalies such as pulmonary hypoplasia, a horseshoe lung, CPAM, a bronchogenic cyst, a diaphragmatic hernia, or cardiovascular anomalies such as an arterial trunk and total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree