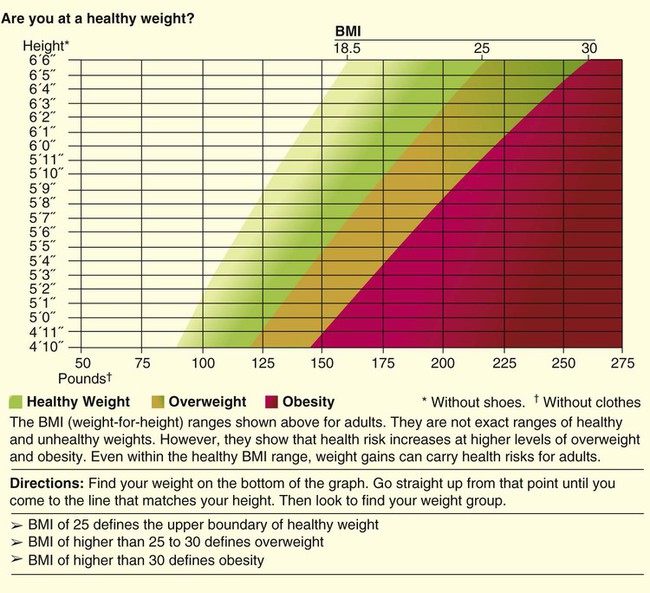

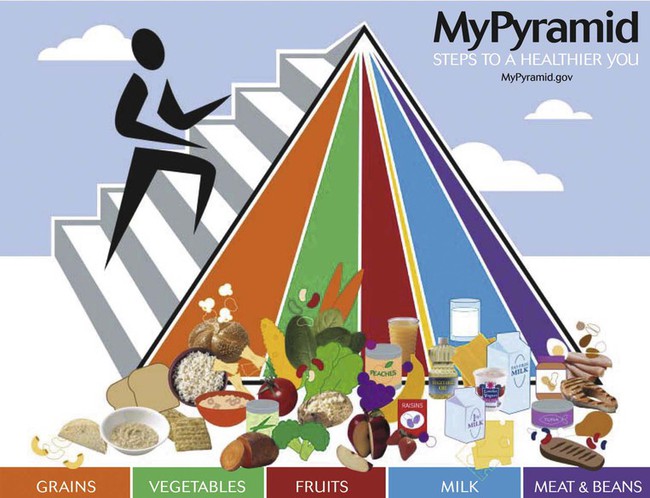

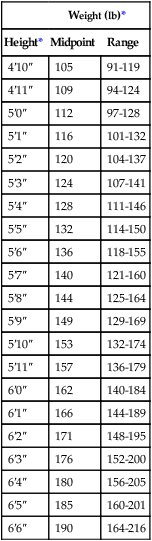

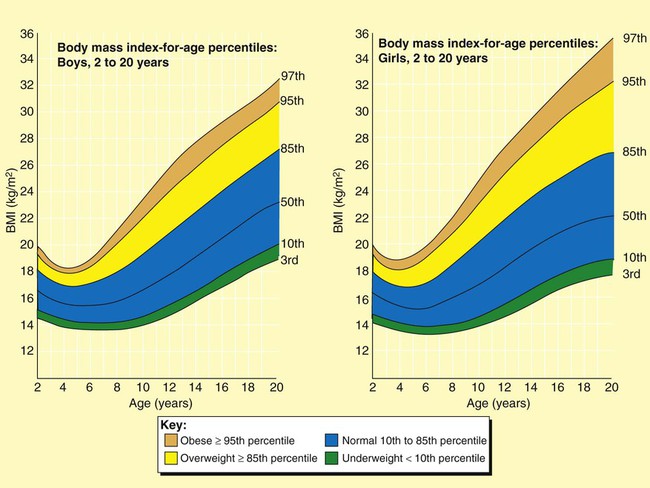

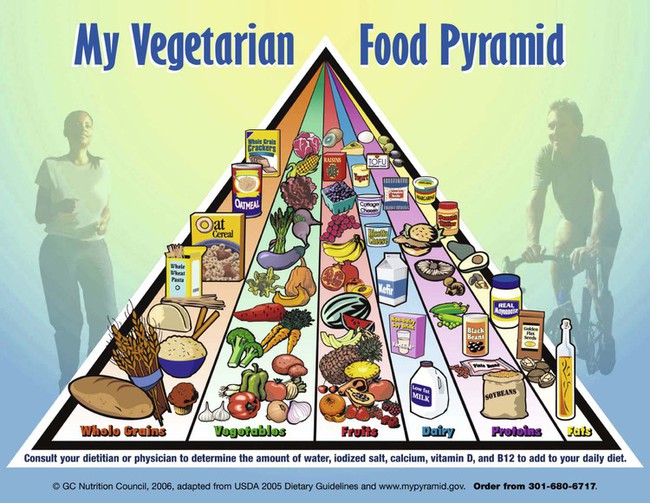

After reading this chapter you will be able to: Registered dietitians or physicians obtain data from numerous sources for nutrition assessment. Interviewing the individual or the caregiver to determine past and current eating practices is most helpful. Medical charts reveal additional information regarding social, pharmaceutical, environmental, and medical issues. In particular, the ABCDs of nutrition assessment—anthropometrics, biochemical tests, clinical observations, and dietary analyses (described subsequently)—lead to nutrition care plans.1 The social history of an individual includes marital status, employment, education, and economic status. Drug-nutrient interactions may be identified from prescribed medications that lead to potential nutrient deficiencies. Environmental issues could point out the difficulties the individual has in procuring, storing, or preparing food. The education attained by the individual could determine the potential for understanding and applying nutrition counseling. The economic status of the individual may drive certain food choices.2 Box 21-1 presents an overview of the information to incorporate into a nutrition assessment. A measured height and weight is preferred, but the clinician may ask the patient or caregiver for the height and weight. When the data are recorded, a notation should be made of the date and whether the height and weight were stated or measured. The height and weight can be evaluated to determine weight status by comparing actual body weight with ideal body weight. Table 21-1 shows healthy weights for adults. Ideal body weight may also be determined using the Hamwi formulas. To estimate ideal body weight in pounds, the following simple formulas (Hamwi method) can be used: TABLE 21-1 From Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, Washington, DC, 1995, Government Printing Office. A more useful number, the body mass index (BMI), may also be calculated. This number is a handy tool for determining the category of body weight: underweight, healthy weight, overweight, obese, or morbidly obese (Figures 21-1 and 21-2). BMI numerically states the relationship of weight to height. The formula used to calculate BMI is as follows for measurements in kilograms and meters: The following formula is used when the weight and height measurements are in pounds and inches: An Internet calculator for BMI is available at: http://www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/. A healthy weight is defined as a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 for adults or a BMI-for-age between the 10th and 85th percentiles for children.2 A BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 indicates excessive weight in adults and a BMI-for-age between the 85th and 95th percentiles indicates excessive weight in children. Obesity is defined as a BMI greater than 30 in adults and greater than the 95th percentile in boys and girls 2 to 20 years old. Adults who are categorized as underweight have a BMI less than 18.5, and underweight children have a BMI-for-age in the 10th percentile (see Figures 21-1 and 21-2).3,4 Undernutrition classifications include kwashiorkor and marasmus. Typically seen in children 6 to 18 months old in deprived areas of the world, marasmus results from an extreme lack of calories and protein over a long time. “Matchstick” arms and obvious lack of muscle and fat characterize a child or adult with marasmus. Kwashiorkor results from a more sudden lack of protein and calories, as in a first-born infant weaned suddenly on the arrival of a new sibling, when a diet of nutrient-rich breast milk is traded for a nutrient-poor, cereal-based diet.2 The protruding belly and edematous face and limbs that are characteristics of kwashiorkor result from a lack of circulating proteins needed to maintain fluid balance and to transport fat out of the liver. Numerous sequelae accompany changes in the liver. Infections and parasites may also cause the enlarged belly seen in kwashiorkor.2 Some patients exhibit combined kwashiorkor and marasmus from protein and calorie deprivation over an extended period. A mixture of loss of muscle and fat and circulating albumin is evident in the extreme wasting and edema that are present. Other anthropometric measurements useful in nutrition assessment are arm muscle area (index for muscle) and skinfolds (measures of fat), bioelectric impedance analysis devices, and more sophisticated imaging technologies. These methods are generally expensive and time-consuming and are not relevant in the clinical setting but may be more useful in research settings.5 Measurement of the triceps skinfold is done on the right arm at the midpoint between the acromion process of the scapula and the inferior margin of the olecranon process of the ulna. The arm should be bent at a 90-degree angle at the elbow to mark the midpoint. The arm hangs by the side with the palm facing anteriorly as a caliper is used to measure a pinch of skinfold. The thumb and index finger of the left hand of the measurer grasp the skinfold while the caliper is placed approximately The triceps skinfold (TSF) measurement is used to calculate the arm muscle area (AMA). The result indicates muscle stores available for protein synthesis or energy needs. Changes over time in AMA show whether the patient has been deprived of protein or calories; AMA is one of the markers of nutrition status and can be a predictor of mortality.6 The formula to calculate AMA is as follows: where MAC equals midarm circumference. A factor for sex is included for a corrected AMA formula because this accounts for bone area and provides a more accurate assessment of bone-free muscle area.7 Standards have been established for age groups throughout the life span.5 Laboratory values of particular significance used in assessing nutrition status include serum proteins. PEM may be reflected in low values for albumin, transferrin, transthyretin, and retinol-binding protein. Blood levels of these markers indicate the level of protein synthesis and yield information on overall nutrition status. However, inadequate intake may not be the cause of low values; certain disease states, level of hydration, liver function, pregnancy, infection, and medical therapies may alter laboratory values for each of the circulating proteins.8 Other visceral proteins that may help evaluate nutrition risk are positive acute phase reactants and include fibronectin, insulinlike growth hormone, and C-reactive protein. Albumin constitutes most protein in plasma and is commonly measured at minimal cost. The half-life of albumin is 14 to 21 days, which reduces its usefulness for monitoring the effectiveness of nutrition in the critical care setting.8 The general availability and stability of albumin levels from day to day make it one of the most useful tests for assessing long-term trends (Table 21-2). It is important to determine an albumin value before the onset of disease or insult of injury. In combination with other findings, such as hair pluckability, edema, and poor wound healing, a serum albumin level less than 2.8 g/dl helps differentiate kwashiorkor from marasmus.9 Table 21-3 compares the two forms of PEM.10,11 TABLE 21-2 TABLE 21-3 Comparison of Two Primary Forms of Protein-Energy Malnutrition Transferrin is the transport protein for iron. It has a half-life of 8 to 10 days and is a better indicator of improved nutrition status than albumin. However, lack of iron influences transferrin values along with numerous other factors, including hepatic and renal disease, inflammation, and congestive heart failure.8,12 Transthyretin, also called prealbumin, has a half-life of 2 to 3 days, and retinol-binding protein has a half-life of 12 hours. Each of these proteins responds to nutrition changes more quickly than either albumin or transferrin. However, numerous metabolic states, diseases, therapies, and infections influence the laboratory values.13 These two tests are more costly than testing for albumin. Levels of each protein are influenced by many factors other than nutrition status. Because these conditions are so common among critically ill patients, visceral protein markers are of limited usefulness for assessing nutrition deficiency and of greater usefulness in assessing the severity of illness and the risk for future malnutrition.14 Inflammatory metabolism causes a 25% decrease in the synthesis of these visceral proteins and causes lean body mass depletion and anorexia. It is important to evaluate their values with positive acute phase reactants (fibronectin, insulinlike growth hormone, C-reactive protein) where there is a reverse relationship. C-reactive protein is an acute phase protein released with infection and inflammation. As transport proteins (albumin and prealbumin) decrease, levels of the acute phase proteins increase. Increased levels of C-reactive protein during stress, illness, and trauma have been linked to increased nutrition risk.12 Because the rate of creatinine formation in skeletal muscle is constant, the amount of creatinine excreted in the urine every 24 hours reflects skeletal muscle mass. Predicted values are based on gender and height, with reference values of approximately 18 mg/kg body weight/day for women and approximately 23 mg/kg body weight/day for men. Values of 60% to 80% of predicted indicate a mild deficit of muscle mass, values of 40% to 60% of predicted indicate a moderate deficit, and values less than 40% of predicted indicate a severe depletion of muscle mass.5 Factors that influence creatinine excretion and complicate interpretation of this index include age, diet, exercise, stress, trauma, fever, and sepsis.12 Impaired immunity (anergy) is a common finding in malnutrition, especially the kwashiorkor type. Two laboratory values, white blood cells and percentage of lymphocytes, have been used as measures of a compromised immune system. The result is often a reduction in lymphocytes, as measured by the total lymphocyte count (TLC): TLC = white blood cells × % lymphocytes. Many nonnutrition variables influence these laboratory values, and their usefulness in assessing nutrition status is questioned.15 Malnourished patients also may exhibit signs of depressed immunity when challenged by certain hypersensitivity skin tests. Because many disease states and drugs are associated with anergy, the value of this test also is limited.16 Pulmonary function test results may change with malnutrition. Weakness of the diaphragm and other muscles of inspiration can lead to reduced vital capacity and peak inspiratory pressures. The strength and endurance of respiratory muscles are affected, in particular, the diaphragm. Healthy lung function has been correlated with dietary antioxidant intake, such as vitamins C and E, beta-carotene, and selenium.17 The physical signs of malnutrition often appear first in selected tissues, such as the hair, eyes, lips, mouth and gums, skin, and nails. Hair that is shiny and firmly in the scalp; bright clear eyes that adjust to light easily; an appropriately red tongue without swelling; gums without bleeding or swelling; skin of good color that is smooth and firm; and nails that are pink, smooth, and firm all are signs of acceptable nutrition status. In addition to malnutrition, other causes of these abnormalities might be medical therapies, anemia, allergies, sunburn, medications, poor hygiene practices, aging, or various pathologies.8 Patients with persistent malnutrition often appear very thin to the point that their ribs and bony structures of the chest are very visible. A patient is said to be cachexic in such cases. The U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have cooperated through the years to recommend balanced nutrition for U.S. citizens. The current graphic showing recommendations, My Pyramid,18 divides foods into groups based on the nutrient contribution of the grouping. For example, the grains group consists of breads, pasta, and rice, which all contribute B vitamins, folate, iron, and protein to the diet. The measure (ounces or cups) of servings is recommended for multiple calorie levels of each of the food groups: grains, protein, dairy, fruits, and vegetables. Consuming the recommended amounts of each should provide balanced, adequate nutrition for a healthy person (Table 21-4). The calorie level is based on age, gender, and activity level. The clinician or patient can go to http://mypyramid.gov to enter an individual’s data and be given the recommended calorie level. A comparison of a 24-hour recall with My Pyramid (Figure 21-3) gives an estimation of the adequacy of the patient’s diet.18 Individuals choosing meatless meals may select foods and number of servings from My Vegetarian Food Pyramid (Figure 21-4).19 TABLE 21-4 Dietary Guidelines for Americans—2005 Compiled from U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Nutrition and your health: dietary guidelines for Americans, Washington, DC, 2005, U.S. Government Printing Office. Nutrition assessment may be accomplished through a process referred to as subjective global assessment. This process uses patient information regarding weight changes, food intake, various symptoms, functional capacity in numerous areas, the disease and its nutrient requirements, and numerous physical traits. Scores are given in each category to determine the subjective global assessment rating of well-nourished, moderately malnourished, or severely malnourished clients.20,21 A healthful diet with added nutrients is essential to a successful pregnancy and to lactation. The demands of the growing fetus and of the nursing infant add to the calorie and protein needs of the mother.22 Ensuring adequate vitamin and mineral intake to support pregnancy and lactation requires a modest increase in all vitamins and minerals compared with the requirements for 19- to 30-year-old women with the exceptions of magnesium; phosphorus; vitamins D, E, and K; and biotin for certain age groups.23–26

Nutrition Assessment

Describe how a comprehensive nutrition assessment is conducted.

Describe how a comprehensive nutrition assessment is conducted.

Describe how to calculate and interpret body mass index.

Describe how to calculate and interpret body mass index.

Describe how to distinguish two forms of protein-energy malnutrition from each other.

Describe how to distinguish two forms of protein-energy malnutrition from each other.

List the biochemical indicators of nutrition status.

List the biochemical indicators of nutrition status.

State what to observe clinically in a malnourished patient.

State what to observe clinically in a malnourished patient.

Describe how to obtain and evaluate a nutrition history.

Describe how to obtain and evaluate a nutrition history.

Describe how to estimate daily resting energy expenditure.

Describe how to estimate daily resting energy expenditure.

List the indications, contraindications, hazards, and limitations of indirect calorimetry.

List the indications, contraindications, hazards, and limitations of indirect calorimetry.

Describe how to prepare a patient properly for indirect calorimetry.

Describe how to prepare a patient properly for indirect calorimetry.

Describe how to interpret the results of indirect calorimetry.

Describe how to interpret the results of indirect calorimetry.

Describe how resting energy expenditure values are adjusted to reflect the actual energy needs of a patient.

Describe how resting energy expenditure values are adjusted to reflect the actual energy needs of a patient.

State the effects of malnutrition on the respiratory system.

State the effects of malnutrition on the respiratory system.

Describe how to identify patients at high risk for malnutrition.

Describe how to identify patients at high risk for malnutrition.

Identify the effect of too much protein, carbohydrate, or fat on a patient.

Identify the effect of too much protein, carbohydrate, or fat on a patient.

State when enteral nutrition and parenteral nutrition are needed.

State when enteral nutrition and parenteral nutrition are needed.

Describe how to identify and minimize the common respiratory complications of enteral feedings.

Describe how to identify and minimize the common respiratory complications of enteral feedings.

State specific nutrition guidelines that apply to patients with specific pulmonary diseases.

State specific nutrition guidelines that apply to patients with specific pulmonary diseases.

Nutrition Assessment

Anthropometrics

Height and Weight

Weight (lb)*

Height*

Midpoint

Range

4′10″

105

91-119

4′11″

109

94-124

5′0″

112

97-128

5′1″

116

101-132

5′2″

120

104-137

5′3″

124

107-141

5′4″

128

111-146

5′5″

132

114-150

5′6″

136

118-155

5′7″

140

121-160

5′8″

144

125-164

5′9″

149

129-169

5′10″

153

132-174

5′11″

157

136-179

6′0″

162

140-184

6′1″

166

144-189

6′2″

171

148-195

6′3″

176

152-200

6′4″

180

156-205

6′5″

185

160-201

6′6″

190

164-216

Body Mass Index Categories

Kwashiorkor and Marasmus

Body Composition

Triceps Skinfold

inch from the fingers. When the caliper is perpendicular to the skinfold, the dial can be easily read.5

inch from the fingers. When the caliper is perpendicular to the skinfold, the dial can be easily read.5

Arm Muscle Area

Biochemical Indicators

Albumin

Level (g/dl)

Interpretation

3.5-5.0

Normal

2.8-3.5

Mild depletion

2.1-2.7

Moderate depletion

<2.1

Severe depletion

Parameter

Starvation (Marasmus)

Hypercatabolism (Kwashiorkor)

Etiology

Inadequate energy intake

Response to injury or infection

Examples

Cancer, pulmonary emphysema

Sepsis, burns

Body habitus

Thin, wasted, cachexic

May be normal, edematous

Rate of malnutrition

Slow

Rapid

Metabolic rate

Decreased

Increased

Fuel

Glucose/fat

Mixed

Catabolism

Decreased

Increased

Gluconeogenesis

Increased

Markedly increased

Glucagon

Increased

Markedly increased

Insulin

Decreased

Increased

Ketogenesis

Increased

Slightly increased

Catecholamines

Unchanged

Increased

Cortisol

Unchanged

Increased

Growth hormone

Increased

Increased

Visceral proteins

Normal

Decreased

Cytokines

Variable

Increased

Immune function

Normal

Impaired

Clinical course

Adequate responsiveness to short-term stress

Infections, poor wound healing, decubitus ulcers, skin breakdown

Mortality

Low unless related to underlying disease

High

Transferrin

Transthyretin and Retinol-Binding Protein

Fibronectin, Insulinlike Growth Hormone, and C-Reactive Protein

Creatinine-Height Index

Immune Status

Pulmonary Function

Clinical Indicators

Dietary Measures

Evaluation of Nutrition History

Food Guide Pyramid

Guideline

Application

Adequate nutrients with calorie needs

Consume a variety of nutrient-dense foods and beverages within and among the basic food groups while choosing foods that limit the intake of saturated and trans fats, cholesterol, added sugars, salt, and alcohol

Meet recommended intakes within energy needs by adopting a balanced eating pattern, such as the USDA Food Guide or the DASH Eating Plan

Weight management

Maintain body weight in a healthy range, balance calories from food and beverage calories, and increase physical activity

To prevent gradual weight gain, make small reductions in calorie intake and increase physical activity

Physical activity

Engage in regular physical activity

Achieve physical fitness through cardiovascular conditioning, stretching, and resistance exercises

Food groups to encourage

Consume sufficient amounts of fruits and vegetables

Choose a variety of fruits and vegetables every day

Consume ≥3 oz equivalents of whole-grain products per day; half of the grains should be whole

Consume 3 cups per day of fat-free or low-fat milk or equivalent milk products

Fats

Consume 10% of calories from saturated fats and <300 mg/day of cholesterol, and keep trans fats as low as possible

Keep total fat intake between 20% and 35% of calories

Choose lean, low-fat, or fat-free meat, poultry, dry beans, milk, and milk products

Limit intake of fats and oils high in saturated and trans fats, and choose products low in such fats and oils

Carbohydrates

Choose fiber-rich fruits, vegetables, and whole grains often

Choose and prepare foods and beverages with little added sugars

Reduce incidence of dental caries by practicing good oral hygiene and consuming sugars and starches less often

Sodium and potassium

Consume <2300 mg of sodium per day (approximately 1 tsp of salt)

Choose and prepare foods with little salt

Consume potassium-rich foods (i.e., fruits and vegetables)

Alcoholic beverages

Alcohol should be consumed in moderation

Pregnant and lactating women, individuals who cannot restrict their intake of alcohol, patients taking medications that interact with alcohol, and patients with specific medical conditions should not consume alcohol

Food safety

Clean your hands, food contact surfaces, and fruits and vegetables; meats and poultry should not be rinsed

Separate raw, cooked, and ready-to-eat foods while shopping, preparing, or storing foods

Cook foods to a safe temperature to kill microorganisms

Refrigerate perishable food promptly, and defrost foods properly

Avoid raw (unpasteurized) milk or any products made from unpasteurized milk, raw or partially cooked eggs or foods containing raw eggs, raw or undercooked meat and poultry, unpasteurized juices, and raw sprouts4

Subjective Global Assessment

Considerations Throughout the Life Span

Pregnancy and Lactation

Nutrition Assessment