Fig. 6.1

Esophageal compression on anterior–posterior videofluoroscopic esophagram caused by upper esophageal sphincter (black arrows)

Fig. 6.2

Diagram of thoracic compressions on the esophagus caused by the aorta and left mainstem bronchus. (Anatomy of the Esophagus. Authors: Najam, Azmeena, Ajani, Jaffer, Markman, Maurie, Book title: Atlas of Cancer, Published Date: 2003-01-16)

Fig. 6.3

Esophageal compressions on anterior-posterior videofluoroscopic esophagram caused by upper esophageal sphincter (short black arrows), aortic arch (black arrowheads), and left mainstem bronchus (long black arrow)

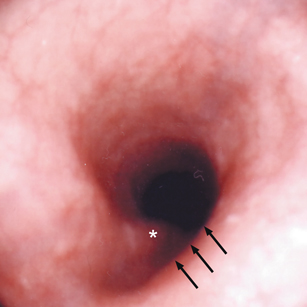

Fig. 6.4

Esophageal compressions on esophagoscopy caused by aortic arch (black arrows) and left mainstem bronchus (asterisk)

Fig. 6.5

Esophageal compression on videofluoroscopic esophagram caused by the diaphragmatic pinch (black arrows)

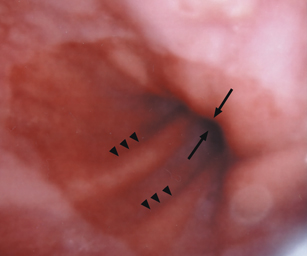

Fig. 6.6

Esophageal compression on esophagoscopy caused by the diaphragmatic pinch (black arrows). Gastric rugae (black arrowheads) extend above the diaphragm indicating the presence of a hiatal hernia

As the PES closes, esophageal peristalsis transports an advancing bolus along the entire esophageal body through a relaxed lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The LES relaxes with the initiation of the pharyngeal swallow and remains open until the bolus advances into the stomach. Although the LES relaxes with the initiation of the pharyngeal swallow on manometry, the LES does not open on fluoroscopy until it is distended by an advancing bolus . The normal swallow-induced esophageal contraction is referred to as primary peristalsis. Peristalsis is visualized fluoroscopically as a stripping wave (Fig. 6.7). A normal esophageal stripping wave transmits a bolus at approximately 2 cm/s. Thus, a bolus should clear the normal 25 cm esophagus in less than 15 s. Liquid barium should proceed throughout its entire length in one smooth motion. Barium tablets may proceed more rapidly in an upright individual as transit may bypass peristalsis and the tablet may drop into the stomach by gravity alone. The esophagus may shorten up to 3 cm during bolus transit in response to the normal contraction of the longitudinal esophageal muscle. Secondary peristalsis occurs irrespective of a pharyngeal swallow. It occurs in response to esophageal chemical (acid) or mechanical (distension) stimulation . The secondary contractile stripping wave occurs similar to the primary wave but initiates at the level of the stimulation and not in the pharynx . Secondary peristalsis is considered a function of normal esophageal biomechanics. It is an essential mechanism to clear the esophagus of retained and regurgitated food (reflux). Tertiary peristalsis is simultaneous, isolated, nonperistaltic esophageal contractions that occur irrespective of coordinated peristalsis (Fig. 6.8). They are nonpropulsive and are considered a sign of esophageal dysmotility. They are not part of normal esophageal function. Profound tertiary contractions can be seen in esophageal spasm and give the appearance of a corkscrew esophagus (Chap. 11). They may be associated with underlying gastroesophageal reflux .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree